- Inshore Fishing

- Offshore Fishing

- Download ALL AT SEA

- Subscribe to All At Sea

- Advertising – All At Sea – Caribbean

A Look Back at the 1968 Golden Globe Race and How it Changed the Sport of Sailing

You know you want it...

Mocka Jumbies and Rum...

Writer Frank Virgintino looks back at an event that changed the sport of sailing and reflects on how one man’s quest for glory ended in tragedy.

The remains of the trimaran Teignmouth Electron lay stranded on Cayman Brac in the Cayman Islands. Where is Cayman Brac? It is one of the two ‘Sister Islands’ which are part of Grand Cayman (see free cruising guide at: www.caymanislandscruisingguide.com)

In 1968 the London Sunday Times offered a prize for the first person to sail solo, non-stop around the world. Inspired by Sir Frances Chichesters recent solo, one-stop circumnavigation, the Golden Globe Race attracted the world’s best sailors.

To put the Golden Globe Race in true perspective, consider that it predated GPS and all of the other electronic navigation aids available today. There was no satellite radio or tracking system.

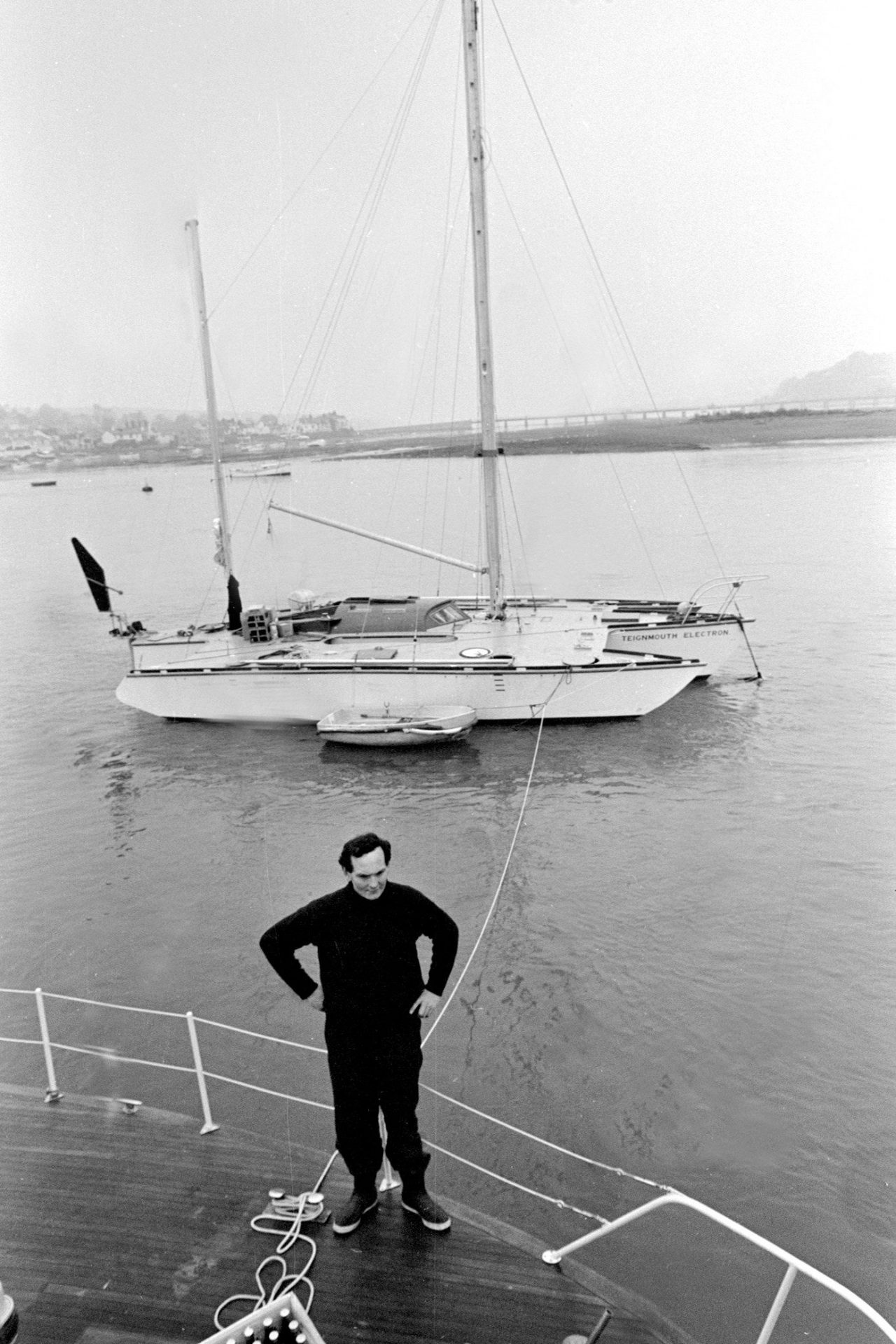

Teignmouth Electron’s sole voyage was a race which started with nine competitors and spanned eight months in 1968 – 1969. The man who owned and skippered Teignmouth Electron, Donald Crowhurst, never returned from the sea. While the race was the Electron’s first and only voyage, it was her sailor’s last.

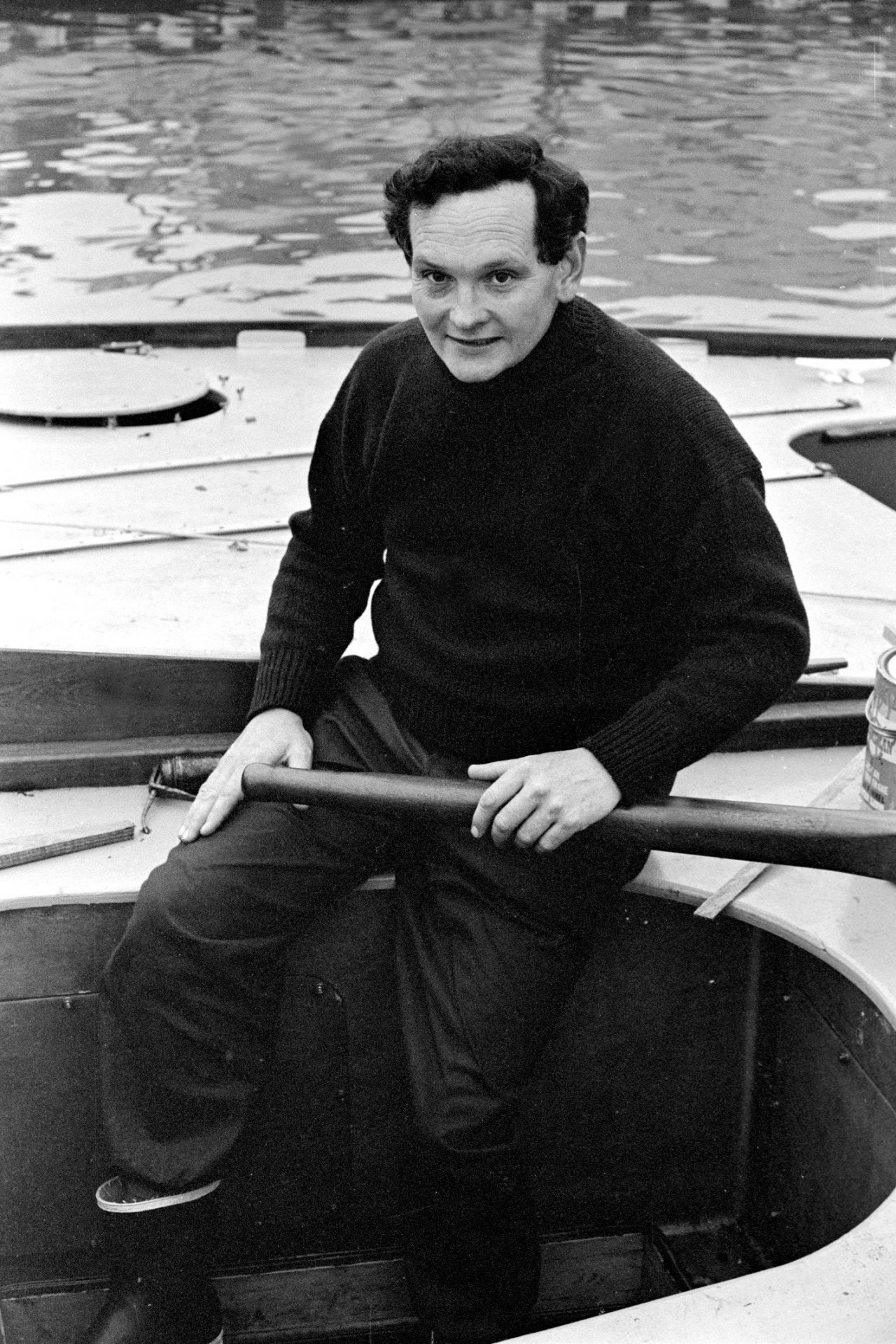

Donald Crowhurst was an English businessman and trained electronics engineer whose company was on the ropes. For him, simply completing the race represented a potential reversal of fortune.

Both he and his boat were inadequately tested. The safety inventions that Crowhurst had planned to incorporate and then market after the voyage were unfinished. Basically a weekend sailor lacking any blue water experience, Crowhurst and his boat crossed the starting line on the last possible day.

Less than two weeks into the race, the price for inexperience and hasty preparation became clear and Crowhurst decided to forego the circumnavigation and falsify his navigation logs. His plan was simple: he would remain in the South Atlantic until lapsed time would reasonably allow him to ‘reenter’ the competition near the end of the race.

What Crowhurst didn’t know for sure but probably suspected was that the race committee had become more than a little curious about inconsistencies in his intermittent radio reports and that they had taken the initiative to begin a quiet investigation.

Dwelling on his own deceit and possible exposure as a fraud, it is thought that Crowhurst committed suicide by stepping off the back of his boat. From that point on the story of Donald Crowhurst entered into sailing legend.

When the Electron was found adrift and abandoned, Englishman Robin Knox-Johnston automatically won the shortest lapsed time prize. Knox-Johnston immediately pledged his prize to a fund for Crowhurst’s family.

The Electron was found adrift with dirty dishes littering the galley and numerous electronic parts scattered about the cabin at 33o 11 N, 40o 28 W on July 10 1969 by the RMV Picardy . After communicating the find to England and following a search in the vicinity for the Electron’s missing owner, the Picardy , destination Santo Domingo, hoisted the vessel aboard. It was subsequently sent to Jamaica.

How the trimaran finally ended up stranded on Cayman Brac is a mystery.

This story of Donald Crowhurst is complex. It combines undertaking alone – and against the odds – an heroic, grueling task; attempting to salvage the effort by concealment (the only sin of which a god is capable, according to Crowhurst’s complex and elaborate apologia); and the surrender to a madness wherein if one sins as only a god can, then one must be as a god and … must join them. It rises to the realm of classic Greek tragedy.  The story has been the subject of books, notably Tomalin and Hall’s The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst (1970, re-released as a paperback in 2003).

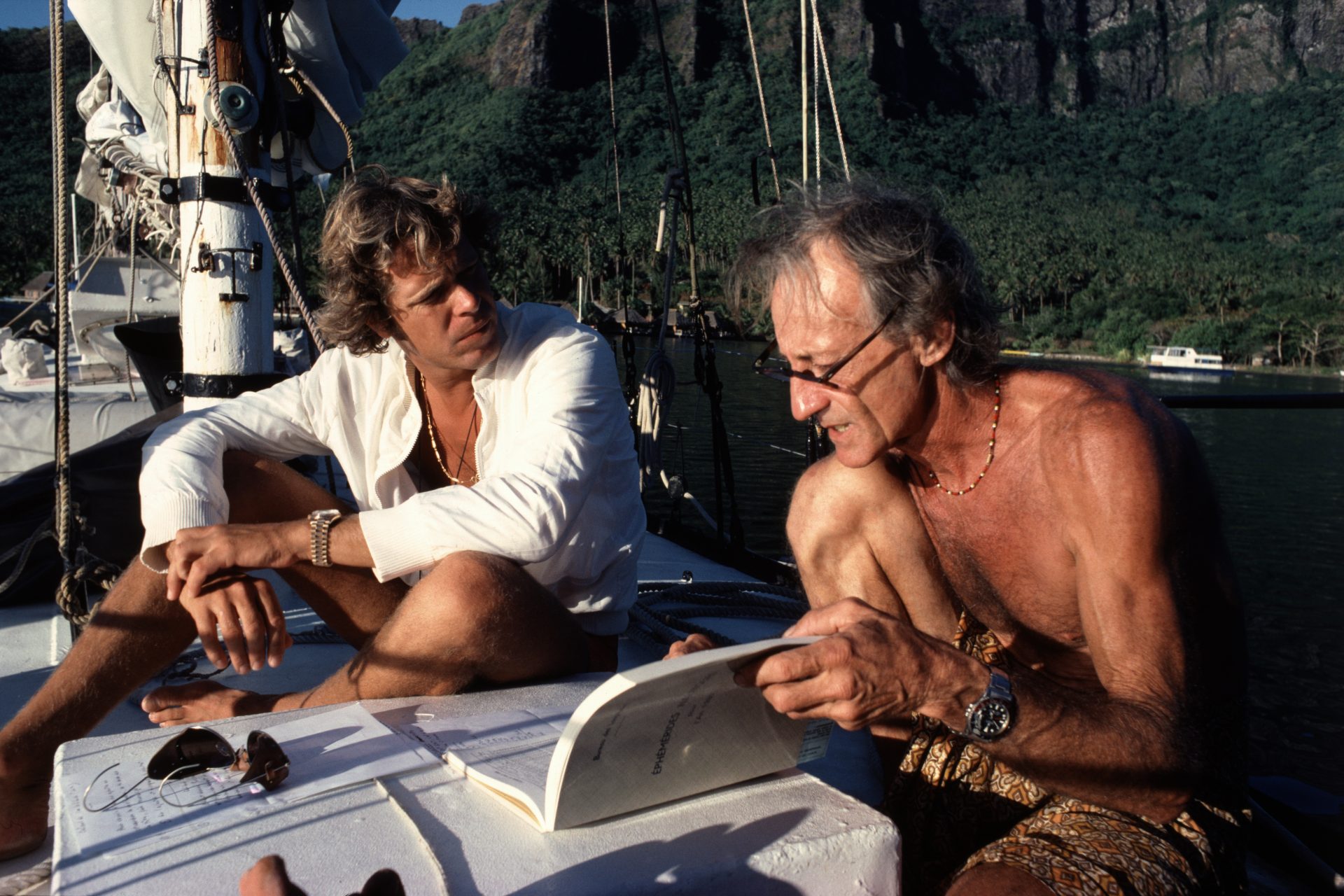

And what of the other eight men who undertook the same heroic task as Crowhurst? Robin Knox-Johnson and Bernard Moitessier were the most celebrated of the nine who undertook the sailing world’s most extreme challenge. Both the ocean and the race rules were harsh mistresses. Peter Nichols, a redoubtable sailor himself, vividly assessed all nine competitors in light of why they took on the challenge, what was at stake in each of their lives, and the known and unknowable conditions they faced at sea in his book A Voyage for Madmen (2002).

For those of you who like to cruise and like to solve mysteries, I suggest you visit Cayman Brac. Aside from actually seeing the Electron you will also get to see Cayman Brac and perhaps Little Cayman as well. You will not be disappointed! You will find the Sister Islands, safe, extremely beautiful, very un-crowded and a joy to behold; albeit that they are ‘off the beaten track’.

Frank Virgintino is author of a number of Free Caribbean Cruising Guides and books which can be found at: www.freecruisingguide.com

Don't Miss a Beat!

Stay in the loop with the Caribbean

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Registration is Open! 50th St. Thomas International Regatta Set for Easter Weekend – March 29-31, 2024

Caribbean sailing: expert tips for finding & keeping crew, 50% entry discount ends december 31, 2023 – 50th anniversary st. thomas international regatta, march 29-31, 2024, so caribbean you can almost taste the rum....

Recent Posts

Sunsail commemorates its 50th anniversary with bvi flotilla in 2024, the life and times of a caribbean one design fleet – st. maarten’s jeanneau 20’s, luxury awaits at the virgin islands boating expo: yacht shop, wine & dine, stay & play, st. lucia unveils new ally for superyachts: blanchard yacht services, recent comments, subscribe to all at sea.

Don't worry... We ain't getting hitched...

EDITOR PICKS

Talkative posts, the seven words you can’t put in a boat name, saying “no”, program for financing older boats – tips and suggestions, popular category.

- Cruise 1741

- St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands 513

- Tortola, British Virgin Islands 432

- Caribbean 424

- Allures yachting

- Garcia yachts

- Dufour yachts

- Fountaine Pajot Sailing Catamarans

- Outremer catamarans

- Allures Sailing Catamarans

- Garcia Explocat

- Dufour catamarans

- Aventura catamarans

- NEEL Trimarans

- Fountaine Pajot Motor Yachts

- Garcia trawler

- Beneteau Motorboats

- Aventura Power Catamarans

- Yacht school

Enchanted by the Ocean: Golden Globe Race 1968-69

"Lord, I am so small, and Your ocean is so great ..."

It was an unprecedented race for pioneer fame, national prestige and financial prize. To sail alone on a sailing boat around the world without stopping is a super serious challenge for a yachtsman even today. What can we say about the 1960s, when there was still no GPS, no radar, no satellite communications; when you were alone with the Ocean - in the truest sense of the word.

They were desperate guys. And this article is dedicated to them.

One of the prerequisites for the Golden Globe Race 1968-69. was the passage of the "three great capes": Horn, Good Hope and Luvin

The riders, regardless of the sport, have an axiom: in order to finish first, you must at least finish.

There were nine of them at the start, and only one at the finish. Total loneliness, constant danger, nervous breakdowns, spiritual search, mystification, the will to win at any cost, suicide. The first round-the-world solo non-stop regatta proved to be a strong test. So strong that, despite the huge resonance, it has not been repeated in this format for 50 years. About how it went Golden Globe Race 1968-69 - in this material.

On April 22, 2019, the yachting community celebrated a significant date: half a century has passed since the day when man first made a non-stop circumnavigation of the world at speed. We remembered and honored Sir Robin Knox-Johnston - the legendary yachtsman who circled the globe non-stop in 312 days during the race The Golden Globe Race 1968-1969.

This is how our memory works - we remember the first, but not the next ones. However, there were nine of them and each deserves its place in this story: Robin Knox-Johnston, Bernard Muatessier, John Ridgway, Charles Bliss, Nigel Tateley, Bill King, Loic Fougeron, Alex Carozzo and Donald Crowhurst.

First, in the 16th century, people first circled the globe on a sailing ship. Then man went around the globe alone - at the end of the XIX. Then, in the second half of the twentieth century, alone with one stop. The next challenge was clear: only a non-stop single round-the-world voyage at speed under sail could break this record. On May 28, 1967 in Plymouth, England, a Brit completed his solo circumnavigation Francis Chichester ... The journey took 226 days, the only stop he made along the way was Sydney, Australia. Chichester's achievement had a deafening effect. Great Britain, the "mistress of the seas", was proud of her son, the rest of the world was jealous. In a few weeks the queen Elizabeth II granted Francis Chichester the title of knight, for the ceremony the same sword was used with which the queen Elizabeth I knighted himself Francis Drake .

Behind sir Francis Chichester followed many admiring eyes. Among them were those who were already planning to break the set record. Seeking to capitalize on this attention, the English newspaper Sunday Times , who also supported Chichester's expedition, wanted to sponsor a yachtsman capable of completing a completely non-stop circumnavigation. The problem was to define this - the newspaper did not want to invest in someone who did not win.

At the age of 65, Francis Chichester embarked on a solo, one-stop, high-speed circumnavigation that became the prologue to the Golden Globe Race 1968-69

Until the point is, King , a retired Royal Navy submarine officer, enlisted the support of the newspaper Express . Ridgeway who sailed the Atlantic in a rowboat with Blisom , got help from the publication The people ... Tatley managed to negotiate with a music company Music for pleasure (Music for pleasure) about her product placement under the motto "Around the World with 80 Symphonies". Donald Crowhurst The “weekend yachtsman” clearly didn’t come across as a sailor worth betting on. Also - the irony of fate! - did not impress the management Sunday Times and amateur yachtsman Robin Knox-Johnston who contacted the newspaper but was refused. Ultimately he was sponsored Sunday mirror .

Sunday Times found herself in an awkward position. There were no free Britons left, and she did not want to sponsor non-Britons for image and patriotic reasons. There was only one way to get out of this situation - to take control of the entire race.

The publication asked Francis Chichester to announce an unprecedented sailing regatta: around the world alone, non-stop. The challenge was thrown - and the challenge was accepted.

The Sunday Times took over the race and instituted two prizes: first place and best speed

There weren't many rules. One on board, no help, no stops, and the passage of the "three great capes": Horn, Good Hope and Luvin. Any boat, starting between June 1 and October 31, 1968, to cross the harsh Southern Ocean in summer. Finish at any British port. Two prizes: a special prize for the first to finish the race and 5,000 pounds to the one who shows the best time (in current prices it is about 60 thousand pounds).

Sir Francis Chichester , a member of the regatta jury, asked the participants to adequately assess their strengths, given the enormous difficulty and danger of such an undertaking.

And then this story breaks up into nine different destinies.

John Ridgway

June 1, 1968, the first possible day, left Irish Inishmore John Ridgway on a 30-foot sloop English Rose IV ... Literally immediately, a ship from one of the film crews crashed into him. The incident, while not causing serious damage, was clearly not a good sign. It soon became apparent that the vessel was not suitable for such a voyage. Also, it turned out that Ridgeway painfully endures loneliness. At Madeira he met a friend to whom he handed over a photo and the first logbooks. And in return I took the mail and newspapers from him. And right there in the newspaper I read about another rule that had appeared, which forbade taking anything on board - including mail and newspapers.

In 1966, John Ridgway and Charles Blees (another Golden Globe Race) crossed the North Atlantic in a rowboat

Technically, Ridgeway was disqualified due to ignorance of this rule. The moment is undoubtedly debatable. He continues sailing in an even gloomier frame of mind. Out into the South Atlantic. The deck of the boat is gradually deteriorating, in addition, the radio transmitter is out of order. Ahead is a meeting with the Southern Ocean, for which Ridgway is not ready either technically or morally.

July 16 John Ridgway admits defeat and heads to Brazilian Recife , where he ends his participation in the regatta on July 21, 1968. A former naval officer leaves an entry in the logbook: “I have never given up in my life. Now I feel empty ... ”.

So there are eight of them left.

Charles Blies

June 8, a week after his former teammate and current rival in the race, from Humble comes out Charles Blies on a 30-foot sloop Dytiscus III ... He is the only member who has no sailing experience at all. Despite this, Blis bypasses the Cape of Good Hope and ends up in the Indian Ocean. The autopilot mechanism fails there. You need to ask for details, but you can't. Having somehow eliminated the breakdown, Blis continues the race.

However, the question is no longer even in the regatta as such - the question is within the personal limits of capabilities and fortitude. However, the sloop does not feel very confident in the Indian Ocean. The boat turns over regularly, one day - 11 times. The autopilot breaks again.

Leaving is not giving up. Charles Blies will make his solo trip around the world in a few years.

Bliss decides that she will return to this challenge - on a better prepared boat and for her own sake, not racing. On 13 September he heads for East London, a city in South Africa , where September 17, 1968 ceases to participate in Golden Globe Race.

So there are seven of them left.

Alex Carozzo

Alex Carozzo went out on his 66 foot keche Gancia americano from Coase English on the last permitted day, October 31st. He entered the race by accident and quite extravagantly. Already participating in the singles race in the Atlantic, he met there with Ridgway, who started at the Golden Globe. Probably, this meeting motivated the Italian to join this ambitious venture. He returned to England, and according to his own project received in 7 (!) Weeks a ship, ready for a round-the-world trip.

Ketch Gancia Americano Italian Alex Carozzo

He was an experienced yachtsman with experience of transoceanic sailing. His ketch was the largest among the participants in the regatta. and was ready to show good speed characteristics - if the skipper alone copes with the controls.

However, this sailor was not knocked out of the race by the ship's breakdown or psychological distress - his physical health let him down. In the Bay of Biscay Alex Carozzo felt severe pain in the stomach. He was diagnosed with an ulcer. It was impossible to continue the race in such a state. The boat was towed to the Portuguese Porto where on November 14, 1968, just two weeks after the release, Alex Carozzo completed participation in Golden Globe Race.

So there are six of them left.

Bill king left Plymouth on August 24, in a 42-foot junk Galway blazer ii ... For the 58-year-old commander of the Royal Submarine Fleet, the race was not so much a competition as an opportunity to enjoy the beauty of the oceans, which he had previously seen mainly from an underwater perspective. As he himself said, it was a kind of psychological rehabilitation after 15 years of service on submarines. He had planned a solo trip around the world before that. Golden globe race became just a convenient excuse not to postpone the idea on the back burner.

King took on board the simplest food and many books - The Bible, the Koran, Buddhist scriptures, Tolstoy's novels ... He admitted that he had never experienced depression while sailing, because he was fascinated by the beauty that surrounded him.

Bill King saw the race as a kind of "psychological rehabilitation" after years of service in the submarine fleet

However, the rigging of ships of the type "junk" has its own specifics. They do not have shrouds, which is why the mountings of the masts are subject to increased loads. One day northeast of Gough Island in the South Atlantic, King's junk was overturned by 15-meter waves. Both masts were broken. There was no way to continue the race. Galway blazer ii was towed to Cape Town, South Africa .

So there are five of them left.

Loic Fougeron

He sailed from Plymouth on 22 August in a 30-foot sailboat with gaff rigging. Captain browne ... Fougeron was a friend Bernard Muatessier , they went out on the same day, and both refused to take radio transmitters on board.

Loic Fougeron retired from the race not so much due to damage to the vessel as out of common sense

On October 30, he passed the archipelago Tristan da Cunha in the South Atlantic, following King several hundred miles ahead. On Halloween, they are caught in a violent storm, and Fougeron's boat capsizes at night. It seems that "The end is coming, that the sea will crush me, will not allow me to appear on the surface again" , - Fougeron will write down later. The ship is intact, but he decides that he has enough trials - and sets a course for Saint Helena completing the race.

So there are four of them.

Bernard Muatessier

Arguments about whether to win Muatesier Knox-Johnston, had remained in the race, is still ongoing. And, like all disputes containing the condition "if", they do not make sense.

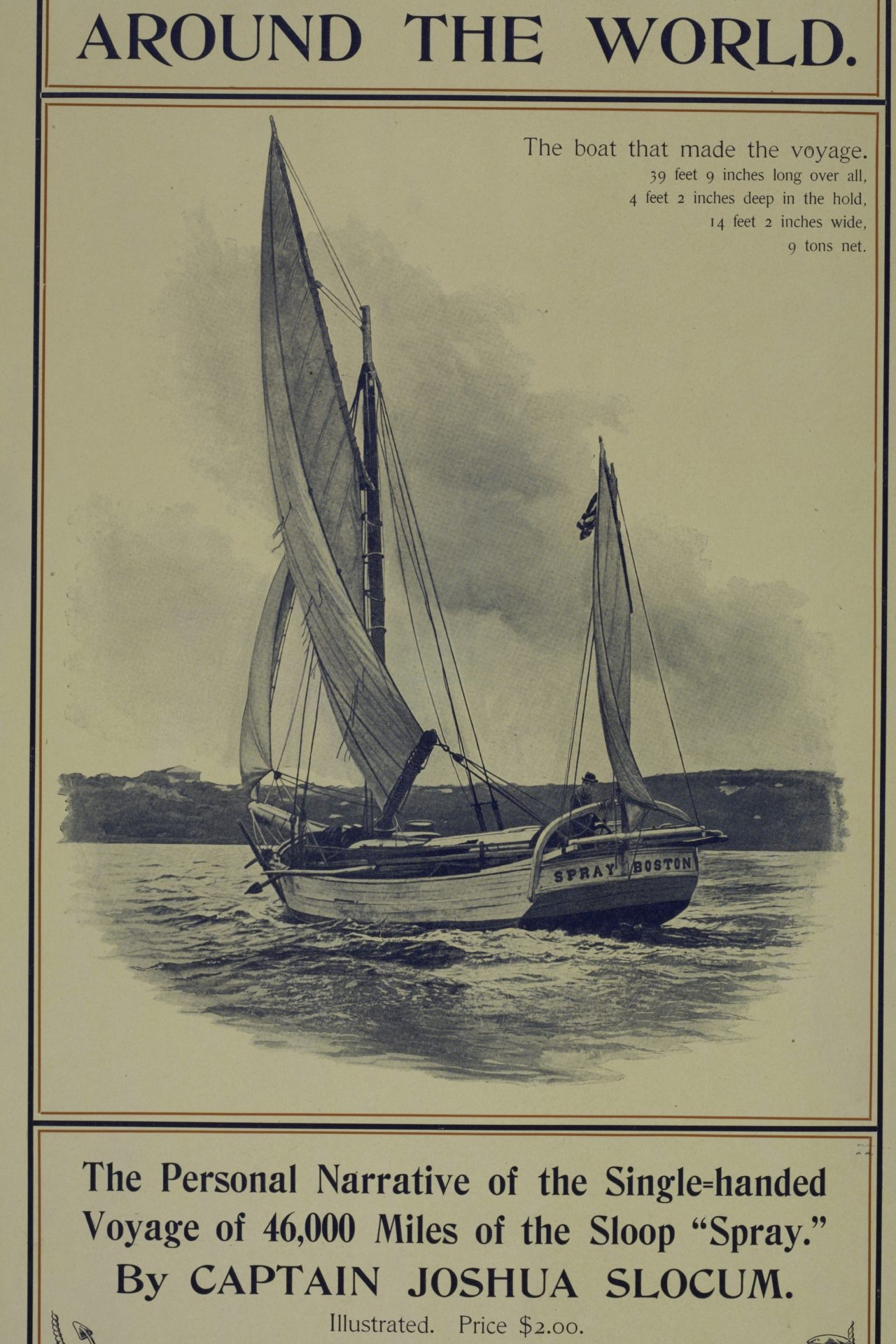

This thin, if not puny, Frenchman was one of those people who are usually labeled "strange" in the mass consciousness. His 39-foot ketch Joshua was named after an American Joshua Slocama - the first person to make a solitary circumnavigation in 1895-1898. He was born in French Indochina, was known as a "tramp of the South Seas", did not like and did not understand Europe.

A romantic, unmercenary and idealist in love with the sea, he started on August 22, when Knox Johnston has been in the ocean for 69 days. With extensive experience in single transitions, Muatesier showed excellent time, walking more than twice as fast as Knox-Johnston. By the beginning of December Knox Johnston fought headwinds in the South Pacific, and Muatesier approached Tasmania. Mid january at Cape Horn they were separated by only 20 days ... While maintaining such dynamics, he could show not only the best time - but also come to England at the same time as Knox-Johnston.

Without formally completing the race, Muatesier, nevertheless, did not lose it - at some point he just went to his personal trip around the world.

However, is the harsh and beautiful infinity of the ocean worth the vanity in which people on earth are immersed? Even if fame and money are your reward? Bernard Muatessier answers himself to this question: no, not worth it.

The commercialization of sailing is incompatible with Muatessier's vision. After experiencing depression and doing yoga, he uses a homemade sling to send a message on board a passing ship, in which he says that drops out of the race because he is happy at sea. However, this is not the end of his circumnavigation: Muatesier makes one and a half turns around the globe and, having covered 37.5 thousand nautical miles in 10 months, finishes in his personal regatta at Tahiti .

So there were three of them.

Nigel Tatley

Nigel Tatley left Plymouth on 16 September in a serial 22-foot trimaran Victress , where he lived with his wife and children. The trimaran could reach an impressive speed of up to 22 knots, but it also had a significant drawback - in the event of a rollover, it could not be returned to its original position. Moreover, an ordinary serial, intended for simple family transitions, was not ready for such a race. But Tatley had no other ship. A restrained and smart naval officer, probably the most methodical of all the participants, he was a gourmet and aesthete. On board Victress had a great speaker system that was the reason Tatley was backed by a classical music label.

Tetley raced a serial 22-foot trimaran that served as his and his family's home

Despite the problems with the boat, Tatley looked after her carefully and steadily moved forward, showing a good average time. He could not finish first - but he could take the prize for the best speed.

May 20, 1969, in the North Atlantic, near the Azores and just a thousand nautical miles from home, Tatley got caught in a severe storm. Early the next morning, he was awakened by the sound of a tree breaking. The left float fell off, making a hole in the main body Victress ... The water was coming in too quickly. Nigel Tatley managed to transmit the signal Mayday , to which he immediately received an answer, and left the ship just before it sank. On the evening of May 21, he was picked up drifting on a life raft.

So there were only two of them.

Donald Crowhurst

However, “two” is not the most correct formulation. Crowhurst did not race, but simulated it standing in the South Atlantic, forging logbooks and hoping to win a £ 5,000 prize for best speed. He hoped that no one would carefully check the reports of the third finisher, and this would give him the opportunity to hide the deception. But after Tatley was eliminated and Chichester announced that he would study Crowhurst's route, that plan collapsed.

About him - like Robin Knox-Johnston - most of all written and filmed in the context of this regatta. A swindler, a deceiver, a madman on the one hand. And on the other hand, a person who believes in his own, albeit strange, ideas, who wants happiness and prosperity for his family.

Donald Crowhurst expected his 40-foot Teignmouth Electron trimaran to deliver impressive speed, but things went wrong from the start.

He wanted to be the "ideologue" of such a race. But Sunday Times ignored his idea - just a year later to announce it under the impression of a record Francis Chichester ... He wanted to hit the road on Gypsy moth iv , Chichester's boat - but was refused due to lack of experience.

Finally, he found a sponsor for the project of his own trimaran, mortgaging a company and a house for this - and hoping to cover the debts from the prize money. But everything went wrong from the very beginning. And this "not so" ultimately led him to a choice between life and death, deception and dishonor of his family.

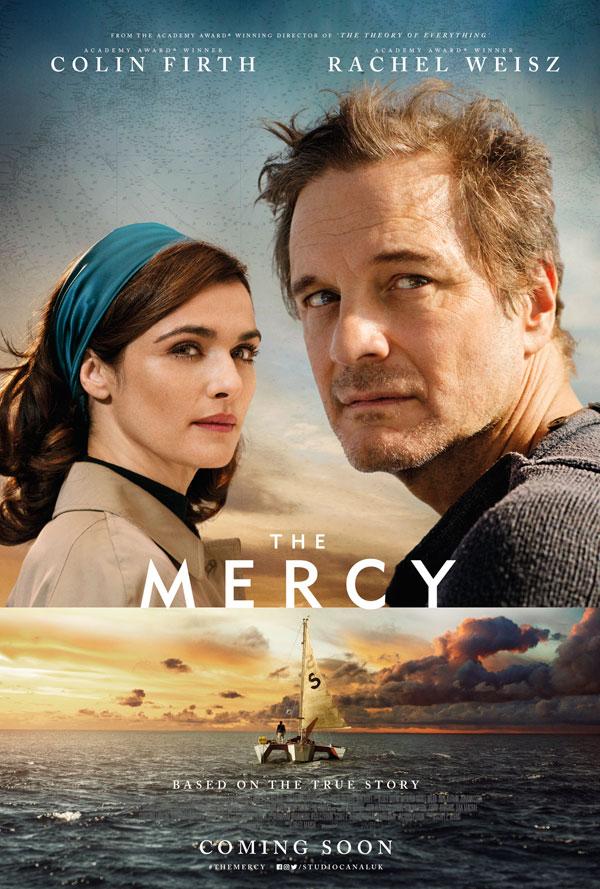

History Donald Crowhurst well known to those interested in yachting. Especially thanks to the movie "Race of the Century" (in original "The Mercy" - "Mercy" , but also with the value "Forgiveness" ), released in 2018.

Probably the most impressive thing about Crowhurst’s fate is not the unsightly part where he was going to forge the logbooks by faking his trip around the world. And the one where he, already experiencing a mental disorder, "playing chess with cosmic beings" and reflecting on his position, decides to abandon his venture. And 20 minutes before the suicide, he makes an entry in the logbook: "There is only one perfect beauty in the world - this is the beauty of truth."

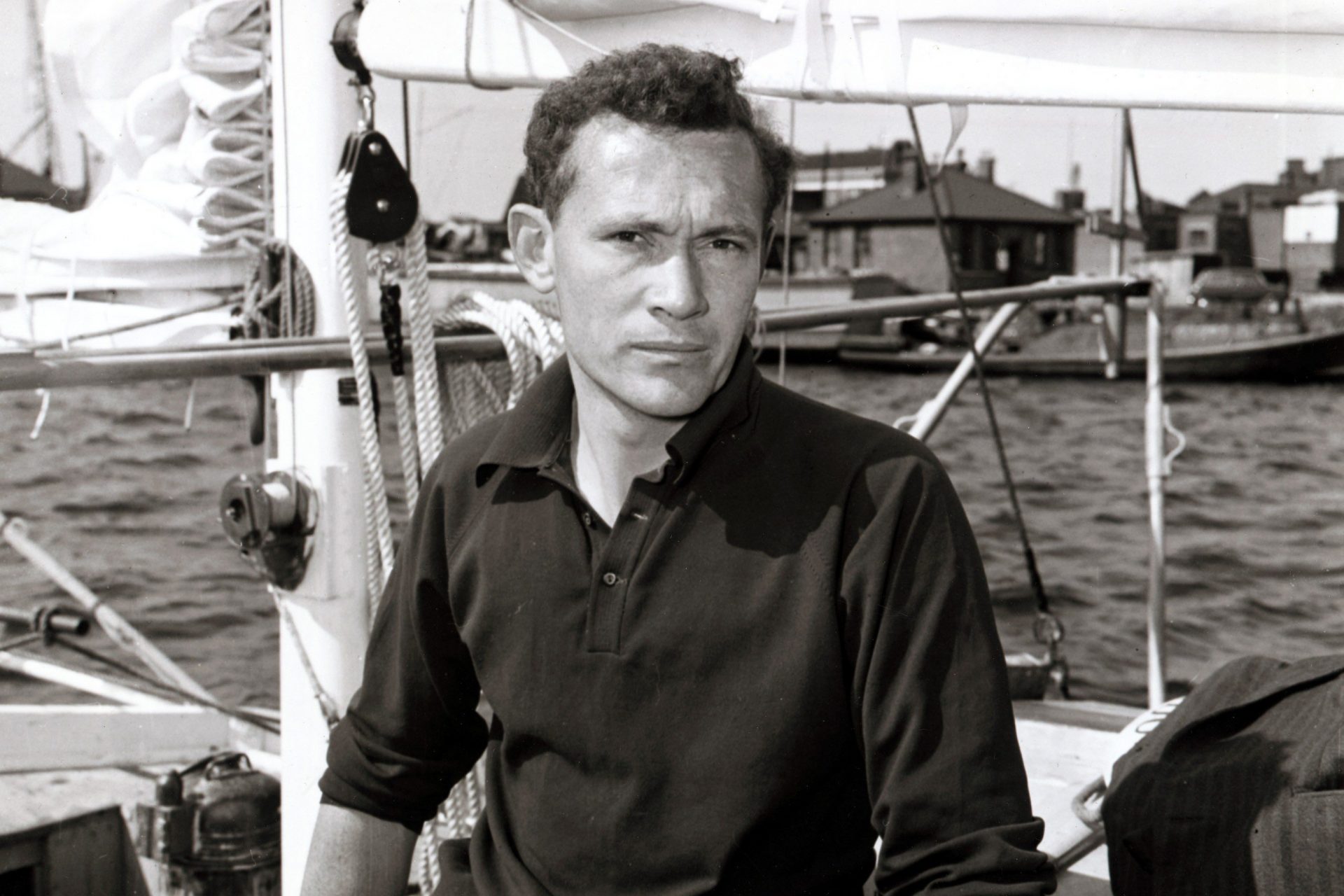

Robin Knox-Johnston

His story is best known - such is the fate of the winners. Finished the race Golden globe race ... Gave the money won to the family Donald Crowhurst ... He became a Knight of the Order of the British Empire, and then a knight. I went (and does!) A lot under sail. I recently celebrated my 80th birthday.

It was he, a native of the merchant fleet, who, according to journalists, was "a very weak contender for victory," on his old-fashioned but reliable keche Suhaili , the only one passed that crazy regatta to the end.

Many years, Sir Robin!

The legendary yachtsman, Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, remains today a hymn to the human spirit - and yachting!

John Ridgway founded School of Adventure , and in 1977-78. took part in Whitbread round the world race ... 1983-84 together with another yachtsman on a keche English Rose VI , made a non-stop circumnavigation, setting the record of his time - 203 days.

Charles Blies indeed returned to his circumnavigation in 1971, becoming the first person to go non-stop in 292 days against the trade winds and currents. For this he received the title of Commander of the Order of the British Empire. Walked a lot, participated in other races and set records.

Alex Carozzo built boats, wrote books, participated in ocean races of multihulls. In 1990 on a homemade boat Zentime passed the Atlantic along the Columbus route.

Bill king in 1973, after several attempts, he completed his circumnavigation. He died in 2012 at the age of 102, becoming the oldest submarine commander in a WWII veteran.

Bill King completed his trip around the world with several attempts and lived to be 102

Loic Fougeron returned to normal life, and continued to sell in a more relaxed mode. He wrote several books, died in 2013 at the age of 86.

Bernard Muatessier never got along with civilization. He defended nature, got to know himself, interrupted himself with various earnings, especially after he lost his ketch in a shipwreck in 1982. He has written several books, the most famous of which is - "Long way" ... Left the world in 1994.

Bernard Muatessier did not get along with the world of his day, remaining in the eyes of the majority of the "eccentric"

Nigel Tatley received a consolation prize of 1000 pounds for participation in Golden globe race ... But this was not enough to build a new trimaran. Tatley was looking for money, the book he wrote sold poorly. In February 1972, he left home and disappeared. He was found hanged three days later in the forest. The police left the conclusion open, finding no sufficient evidence for the suicide theory.

History Donald Crowhurst quite well known for the film "The Mercy" (in Russian translation - "Race of the Century"), in which Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz played

A boat Knox Johnston, Suhaili , still belongs to him and stands at the National Maritime Museum in Falmouth, UK. Restored boat Muatessier, Joshua , is in the Maritime Museum in La Rochelle, France.

Golden globe race became the impetus for other, less harsh, solitary circumnavigations: BOC Challenge (today - Velux 5 Oceans Race ) and Vendée Globe ... The second Golden globe race started 50 years after the first - July 1, 2018. We will write about it next time.

Dmitry BUSHUEV

News and articles

When it comes time to head out to sea, one of the perks of smartphones and tablets is that you can install a ton of useful apps on a tiny device.

The Naval Group has taken 3D printing a step further for the marine world by using it to produce a large propeller. An innovation that can come to the maritime and pleasure craft industries

A surprise for connoisseurs and admirers of true French and impeccable! The new catamaran Fountaine Pajot New 67. Aged in the best traditions of the company, the New 67 is the quintessence of excellence. Every inch of this catamaran breathes luxury. He is pompous, majestic, charismatic.

1968's infamous Golden Globe Race is being restaged and two Australians are competing

News ticker, election results.

Follow all the results of the Brisbane City Council election and Queensland by-elections at our full results page

Solo yacht races don't always go to plan. But the Golden Globe Race in 1968 went down in infamy, both for its test of the sailors' mettle and the tragic events that unfolded.

The race is being restaged for its 50th anniversary and two Australians are trying their luck on the open sea.

Former Navy officer Mark Sinclair was 10 years old in 1968 and captivated by the race. When he heard it was being held again, he knew he had to be part of it.

"There was no choice; I was compelled to participate," Mr Sinclair said. "The clock has been wound back 50 years and I have the opportunity to hop onto this time machine."

On Sunday, he joins fellow Australian Kevin Farebrother and 16 other skippers at Les Sables d'Olonne in France for the start of their 30,000-mile voyage which is likely to take about eight or nine months.

A race beset by tragedy

The 1968 Sunday Times Golden Globe Race was the first-ever non-stop solo circumnavigation of the globe. Nine men set out to compete, but only one would finish.

All but four contenders retired before leaving the Atlantic.

The last men in the running were Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, Nigel Tetley, Donald Crowhurst and Bernard Moitessier.

In the lead, and with just 1,100 miles to go, Tetley sank and had to be rescued.

Faced with the prospect of likely victory and the media circus that would no doubt ensue, Moitessier, a romantic and ascetic French sailor of some renown, slingshotted a note in a film canister onto a passing boat informing his wife and children that he'd had an epiphany at sea and he would not be back.

"Record is a very stupid word at sea. I am continuing nonstop because I am happy at sea, and perhaps because I want to save my soul," Moitessier wrote.

He continued sailing halfway further around the globe, on to Tahiti, becoming a prominent environmental and anti-nuclear activist.

Mental breakdown

Donald Crowhurst never left the Atlantic in the first place. In the windless mire of the Sargasso Sea, things began to unravel — his boat wasn't up to the journey and neither was he.

Faced with the prospect of financial ruin, he concocted a plan to try and fake having completed the full voyage, fudging the logbooks then planning to follow the others in as runner-up. This would allow him to avoid excessive scrutiny on the ship's log, but perhaps avert bankruptcy.

When he caught wind that Tetley had sunk, Moitessier had absconded and it became apparent he might win by default, his descent into psychological breakdown accelerated — something captured in the increasingly manic diaries he kept.

In a rambling manifesto, he scrawled mathematical formulas for what he called the "cosmic integral", ultimately reaching the conclusion that "man = 0".

He is believed to have jumped overboard; his body was never found. His boat, the Teignmouth Electron, was found in 1969 with both sets of logbooks aboard. He left behind a young family.

Mr Knox-Johnston was the only man to finish the race on his ketch Suhaili, though on the homeward stretch he spent 10 days doubled over with suspected appendicitis.

"Had I been close to a port, I would have gone in," he told the BBC earlier this month.

Mr Knox-Johnston has restored Suhaili and is leading the yachts out of the harbour on Sunday.

'Chance of a lifetime'

Mr Sinclair, who hails from Adelaide, has been busily preparing his boat, Coconut. A sailing veteran, he anticipates his biggest challenge will be returning to civilisation after it's over.

Mr Sinclair served 20 years in the Royal Australian Navy, at a time when celestial navigation by sextant was still the primary means of navigation.

This should set him in good stead: The skippers in this year's race will be limited to the technology available in 1968, with the exception of an emergencies-only GPS, and sporadic safety check-ins with the event organisers.

Mr Farebrother, a Perth firefighter, is no stranger adventure, having climbed Mt Everest three times.

"The race will be the chance of a lifetime that will test mind and body to the limits," he said.

"The major challenge will be being alone for such a long period with no one to bounce off thoughts and ideas when the going gets tough. I also expect some extreme weather conditions, particularly in the Southern Ocean."

Mr Farebrother heard about the race from a friend a little over two years ago.

"I'm more of a climber than a sailor, but after receiving my friend's message and reading Robin Knox Johnston's book I decided that this race was for me."

He sailed around much of the Australian coast in preparation.

"I sailed Sagarmatha the 6,000 miles from Sydney around the top of Australia to Perth, 2,000 of that was solo, and then I continued preparations for the race in 2018," he said.

Hypnosis of the sea

While there are better safeguards in place this year — including satellite tracking so the contestants' whereabouts will be known to race organisers — this year's entrants will find themselves locked in a relentless and elemental battle nonetheless.

The skippers have an unending list of things to contend with. They are at once a cook, watchman, plumber, navigator and captain — and the rest.

Quite apart from the physical exhaustion, there are psychological factors: combination of isolation and persistent white noise means hallucinations are commonplace among solo sailors. Convincing mirages may present.

The results of a 1972 transatlantic race survey gave a clear indication of just how widespread the phenomenon is: Of the 34 race participants who agreed to take part in the survey, 12 said they experienced a hallucination of some kind, whether visual, auditory or olfactory.

Calenture is a state of hypnosis that sailors may fall into while staring into the vast expanse of the sea — and is often accompanied by a strong urge to allow themselves to be swallowed by it.

In the Southern Ocean, the skippers will find themselves more isolated than anywhere on earth, some four days' in either direction from civilisation.

Mr Knox-Johnston once mused on what effect solo round-the-world sailing, if used as a punishment, might have on crime rates: "It's 10 months' solitary confinement with hard labour."

- X (formerly Twitter)

'It is the mercy'

Donald Crowhurst's last diary entry before he disappeared overboard. Carving by Tacita Dean

07 Feb 2018

The Mercy starring Colin Firth portrays Donald Crowhurst's tragic attempt to sail around the world single-handedly in the first race of its kind. Maritime specialist Jeremy Michell sheds light on the perils of sailing alone, the progress of yacht racing, and the importance of remembering failure.

By Kate Wilkinson

Visit the National Maritime Museum

The thrill of the race

Fifty years ago, the Sunday Times Golden Globe became the first solo non-stop round-the-world yacht race. Building on the international celebrity of Francis Chichester’s circumnavigation in 1966-67, the UK newspaper launched a sailing event to capture the world’s imagination – the ultimate competition of skill and endurance, and open to anyone, amateurs included.

'Yacht racing in this country has always been big, but it tended to be fairly elitist in the past,' says Jeremy Michell, a sailing instructor and part of the National Maritime Museum’s curatorial team, 'The Golden Globe opened up in a more popular mind the idea that people who are not wealthy could go and take part.'

Yachting really began when King Charles II brought his enthusiasm for the activity to England on return from exile in 1660 and raced yachts down the Thames against his brother for huge wagers. In the late 1870s, Lord Brassey achieved the first circumnavigation by a private yacht, building himself a steam-assisted three-masted schooner called 'Sunbeam' and sailing round the world with his family. The boat's figurehead is on display in the National Maritime Museum.

The Golden Globe opened up in a more popular mind the idea that people who are not wealthy could go and take part.

Struggling businessman and sailing amateur Donald Crowhurst was the classic underdog when he entered the 1968 competition. Putting everything into the race, he had signed a contract with his sponsor whose penalty clause meant that he would forfeit his house and business if he didn’t finish.

A doomed adventure

Crowhurst waved goodbye to his wife and four children on the race’s last eligible day aboard the Teignmouth Electron, a trimaran he had barely sailed before setting off. He had planned to equip the vessel with his own safety features, the success of which he hoped would revive his business in maritime navigational technology, Electron Utilisation Ltd. But he hadn’t completed the work before leaving British shores, leaving him in the process of tweaking while sailing.

It didn’t take Crowhurst long to realise how perilously ill-equipped he would be to tackle the waves of the Southern Ocean. If he continued he could die, but quitting would ruin him financially.

For a while it seemed like the plucky amateur could steal the race when Crowhurst started reporting false coordinates showing incredible gains in distance. The deception ended when after weeks alone at sea under immense physical, personal, and financial pressure, he committed suicide. This seemed the most likely cause of his disappearance: when rescuers found his abandoned trimaran, they discovered log books and reams of diary entries showing a collapsing mind.

Crowhurst’s tragedy caused a worldwide sensation. The Sunday Times Golden Globe didn’t run again, and its winner, Robin Knox-Johnston donated his £5,000 winnings to Crowhurst’s grieving family. Knox-Johnston was the only entrant to complete the race, with the other entrants forced to retire along the way.

Solitude at sea

Crowhurst’s behaviour was seen by many as foolish and reckless. He was certainly underprepared, and his false reporting put unnecessary pressure on his fellow competitors. One bad decision followed another, and he was soon lost in a nightmare predicament. How could he let things go so wrong?

Michell says it’s important not to underestimate both the physical and mental challenge of a solo voyage: 'Unless you have done that sort of race, it’s very difficult to make a judgement call as to what the trigger points are to make someone lose their mind in that way and potentially commit suicide.'

Alone at sea, you might catch about 20 minutes of sleep before you’re up again doing something. Performing the roles of a whole crew, you have to be mentally alert all the time. A small change of sound on the boat might wake you up.

Unless you have done that sort of race, it’s very difficult to make a judgement call as to what the trigger points are to make someone lose their mind in that way and potentially commit suicide.

Not only that, without anyone to talk to, 'you’ve got no one to relieve any emotional issues you might have, whether that’s frustration, anger, sadness, loneliness.' Michell knows those who have sailed long distances on their own. During one transatlantic voyage, a friend would call any ship he saw just for the sake of another voice (as well as to confirm his position with their navigation): 'He said you could end up in tears over the most stupid things because it’s the only emotional release you have.'

Though at home it might seem bizarre, when you’re on your own it’s a very different emotional experience, Michell says.

21st Century racing

Though the stakes are high, sailing around the world single-handedly continues to present an appealing challenge. Yachting is as popular as ever and there have been numerous successful racing events world-wide.

What has changed in yacht racing between now and Crowhurst’s day?

Michell lists the improvements to on board technology: the use of hydraulics to keep the yacht stable, electronic equipment for winches, hoisting and dropping sails. Most importantly, there’s the communication. Satellite telephones and beacons allow people to know where you are. In short, 'there’s a lot more of a safety net,' Michell says.

Today it would be unimaginable for a sailor of Crowhurst’s limited experience to take part in such a demanding voyage. The Vendée Globe, a single-handed non-stop round-the-world race founded in 1989, requires its entrants to undertake survival training before participating.

Commemorating failure

Royal Museums Greenwich plays host to some of the most dramatic, awe-inspiring, and successful maritime stories through the objects on display and in conservation. John Harrison’s 18th Century marine timekeepers in the Royal Observatory were the first instruments to solve the problem of finding longitude at sea.

Also in our collection is Donald Crowhurst’s ‘Navicator’ , which he produced and took with him on his doomed voyage. On free display in the Queen’s House is a series of striking photographs by artist Tacita Dean, of Crowhurst’s abandoned trimaran on the coast of the island Cayman Brac. In the National Maritime Museum you can find the artist's carving, of the words 'It is the mercy', which refer to Crowhurst's final diary entry.

So why do we preserve the memory of such a sad event in maritime history?

'It’s always good to remember that life isn’t one long successful winning streak,' Michell says, 'it was never obvious that Britain would be a top maritime nation: it happened through incidences, setbacks, circumstances, failures and successes. In terms of sailing and our yachting industry, it’s exactly the same.'

Crowhurst’s story is a useful reminder of the dangers of yachting, and would have made an impact on the regulation of similar racing events since 1968. 'Out of failure can come some kind of success that makes it safer for other people,' Michell says.

The race’s revival

2018 marks the 50th anniversary of that first ill-fated race. Following a number of books and documentaries over the years, Colin Firth plays Crowhurst in the upcoming film, The Mercy, which is set to fascinate audiences anew. In an earlier preview of the film last year, Robin Knox-Johnston expressed his satisfaction with the film in an interview with Yachting & Boating World magazine.

Later in the year, the Golden Globe race will be re-launched to test sailors under the same circumstances that Crowhurst and Knox-Johnston faced. No modern satellite technology is allowed for navigation – instead competitors must use their skills with instruments such as sextants to make the necessary calculations to steer a good course.

As a safety measure, the race’s website states that:

'All entrants will be tracked 24/7 by satellite, but competitors will not be able to interrogate this information unless an emergency arises and they break open their sealed safety box containing a GPS and satellite phone.'

Also unlike the original race, entrants must show prior ocean sailing experience of at least 8,000 miles and another 2,000 miles solo.

In July the competitors will set off for a challenge like no other.

Even after 50 years, the events of 1968 continue to both haunt and inspire the world’s imagination.

Banner image: 'It is the mercy' by Tacita Dean, courtesy of the artist and Frith Street Gallery.

- Become a member

Member benefits include events such as the exclusive preview screening of The Mercy on 8 November, arranged with STUDIOCANAL, a day before the official cinema release.

Find out more

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

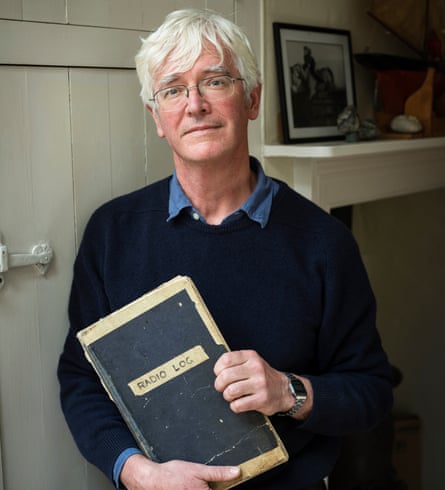

'The boat's been found and he's not on it': tragic sailor Donald Crowhurst's final voyage, by his son

Simon Crowhurst recalls the day his father left on his fateful trip, and explains his reservations about The Mercy, a new film about his story

S imon Crowhurst was eight when he saw his father for the last time. He remembers going out with the rest of the family in a motor boat, to the yacht his father was sailing around the world. “On the deck of the Teignmouth Electron, he kissed us goodbye. I think he said something like, ‘Look after your mother’, and then he was off,” Simon says, nearly 50 years later. “I remember seeing the sail getting smaller and smaller, and disappearing over the horizon. We didn’t think then that we wouldn’t see my father again.”

Simon was nine when he learned his father had died. “My memory was two nuns coming down the drive and speaking to my mother, and my mother taking us to the bedroom I shared with my younger brother, Roger. She sat us down on the bed, said the boat’s been found and he’s not on it. Then she broke down in tears.”

The tragic story of Donald Crowhurst’s last voyage is well-known. On 31 October 1968, the last day the rules allowed, he set off in the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race , a competition to be the first person to sail nonstop single-handedly around the world. He was underprepared and underfunded; his 35ft boat was unsuitable and leaky, no match for the monster waves of the Southern Ocean .

He never reached the Southern Ocean. After being beset by problems and slipping farther and farther behind his competitors, Crowhurst was faced with an impossible choice: to continue to his death, or to return in humiliation and financial ruin (he had staked everything, including his house, on the race). He found a third way: he began to report false positions, fabricating a voyage he wasn’t making, pretending to circumnavigate the globe when in fact he never left the Atlantic.

His yacht would rejoin the race on the return leg – not to be the first to arrive, or to record the fastest time, but to save face. And his house.

Robin Knox-Johnston was first in, and first to circumnavigate the world alone. Another sailor, Nigel Tetley, looked as if he was going to come next and claim the prize for the fastest time, but then he sank (and was rescued). Suddenly, Crowhurst, the only other competitor left in the race, was going to be fastest, claim the Golden Globe and become a national hero. And his log books would come under serious scrutiny.

But Crowhurst never did come home. The Teignmouth Electron was found drifting and abandoned. On board were the log books that charted his actual voyage, together with records that showed how he had made a false speed claim, and indications that he had worked on a false navigational account. They also contained evidence of his psychological state, a rambling, scribbled, crossed-out philosophical interpretation of the human condition. The last page contained the words: “I have no need to prolong the game”; and “It is finished – It is finished IT IS THE MERCY.”

His story has since captured the imagination: there have been books, documentaries, an art installation, an opera, a nod to it in Blackadder, even. And now a new feature film, The Mercy , starring Colin Firth as Crowhurst.

Simon, now 57, understands the obsessive levels of interest in his father’s story. “People can identify with a situation where they feel their options are closed and they’re led into a course of action they wouldn’t normally have anything to do with,” he says, sitting at the kitchen table of his Cambridge home.

I know Simon Crowhurst, who works for the earth sciences department at Cambridge University. He is married to my cousin Alex, which is why he has agreed to talk to me, and why he wouldn’t speak to a journalist who turned up at the door shortly before my visit.

That, incidentally, is how Simon’s mother, Clare, 85, found out there was to be a film with Firth playing her husband: a journalist knocked on the door to ask what she thought about it. She was to be played by Kate Winslet, though Rachel Weisz now plays her opposite Firth.

If it was up to the family, no feature film would ever be made, because it tells the story of events that have affected them deeply, in a range of ways. Because it is disturbing to see the death of your father or husband portrayed on the screen. Because it is a family tragedy, and it has been taken out of their hands. One detail that upset them was that there are three Crowhurst children, rather than four; a brother was cut.

Simon and Alex have written a play about the experience – just for themselves, as a way of letting off steam. It’s very funny, particularly a bit about Firth spending a day with Simon’s mother and sister on an appeasement mission. (Of course it worked: he’s Colin Firth.)

But Simon sees the film-makers’ point of view, too. “Here’s an interesting story, they’ve acquired the film rights, why can’t they tell it? It’s out there, or some of it. But to my family it’s different. It appears intrusive, a kind of violation.”

He’s also generous about the film, and about Firth’s performance. “It captures some of the emotions. Other things are more complex and difficult to put across. In particular, the way my father’s thoughts became very confused.”

This is what you see when you open Crowhurst’s log books, as Simon has. They’re extraordinary artefacts, and to be shown them is like a strange voyage in itself, into the soul of Donald Crowhurst, steered there by his son.

Some of it is routine, functional: sunsights and calculations of positions – both real and imaginary. But then he reports a sudden increase in speed, a new sailing record – 243 nautical miles in a day – a record that never happened. The deception has begun. (Actually, that speed record did sort of happen: later, when Crowhurst was heading back to Britain, he sailed almost exactly that distance in a day. That was typical of him, Simon says. “I think he always hoped and believed that he could make things true eventually, even if they weren’t true at the time.”)

When Crowhurst is delivering his insights on the meaning of life, the universe and everything – that through imagination, humans can become godlike and translate themselves into another dimension – the writing becomes wild and erratic. “In that extreme psychological state, what came to his mind appears to be the Solution, in big flashing neon lights,” Simon says.

Does he understand what his father was trying to get across? “I think there’s a kind of coherence to it, but most of that relates to how he sees his situation at the end of the voyage. His guilt – a lot of it is, by implication, his sense of guilt. And sins – the sin of concealment, of not being where you’re supposed to be, hiding, which is what he’d done.”

How does he feel, reading it now? “I feel very sorry for him. He’s actually somewhere in the margins of the philosophy of madness, you know, sailing over the edge of the world.”

The final page of the log – “It is finished IT IS THE MERCY” – has been torn out, though Simon has the page. He thinks it was the captain of the ship that found the Teignmouth Electron who ripped it, because he felt it would be unbearable for Crowhurst’s wife and children to see.

One of the disturbing things about the new film is that Simon worries his own memories are being overwritten. “You wonder which is true, the memory or the reconstruction.” Does he think about it a lot? “Certainly in times of stress: is this what my father was feeling? Is this what was going on in his head when he was making these decisions that ended so badly?”

And what does it tell him about the meaning of life? “That many questions are still open. On the face of it, we’re a chemical disruption on the surface of a small rock in an obscure part of the galaxy. But, in a way, the profundity of human suffering makes you think: is that all it is?

- The Mercy is released in the UK on 9 February.

- Colin Firth

Clipper Round the World yacht race sets off from London

UK and Ireland commemorate 1979 Fastnet race disaster

Dinghy sailors close in on Great Britain circumnavigation record

Simon Speirs' family fear more lives could be at risk in Clipper race

Michelle Lee becomes first Australian woman to cross ocean solo in a rowboat

Australia's Wendy Tuck wins Clipper Round the World yacht race

‘Shoestring sailor’ Rose’s round-the-world epic still enchants, 50 years on

Ben Ainslie gets America's Cup funding from backer of Brexit and fracking

Rob Mitchell obituary

Hero's welcome for Robin Knox-Johnston - archive, 1969

Comments (…), most viewed.

Sports Unlimited News

Lost At Sea: The tragic story of Donald Crowhurst and the Golden Globe Race

Posted: 8 April 2023 | Last updated: 29 February 2024

The Sunday Times Golden Globe Race

The Sunday Times Golden Globe Race was a non-stop, single-handed circumnavigation race, held in 1968. This was the first ever round-the-world yacht race proposed to the greater public, which sparked a lot of interest amongst sailors worldwide. Arguably one of the most thrilling yet controversial yacht races that took place in the 20th century.

Open to the public

The British Sunday Times newspaper sponsored the event and designed the race to capitalize on the content produced by each voyage. There were no qualification requirements and all competitors were welcome to join the race any time between June 1st and October 31st.

Good prizes

The Golden Globe trophy would be offered to the first person to complete an unassisted, non-stop single-handed circumnavigation of the globe, and a $6,000 prize offered for the fastest time. The prize money would amount to the equivalent of $55,000 dollars today!

Single-handed sailing and its origin

Long-distance single-handed sailing became popular during the 19th century, as numerous sailors would achieve notable crossings of the Atlantic. Joshua Slocum was the first to single-handed circumnavigate the globe during his 1895-1898 voyage. Many sailors have since followed in his footsteps for leisure, glory, or fame.

Nine sailors

Nine sailors started the race; John Ridgway (UK), Chay Blyth (UK), Robin Knox-Johnston (UK), Loick Fougeron (FRA), Bernard Moitessier (FRA), Bill King (UK), Nigel Tetley (UK), Alex Carozzo (ITA), and Donald Crowhurst (UK). Only one sailor made the finish line.

Robin Knox-Johnston

The Sunday Times had their money on young sailor Robin Knox-Johnston and decided to sponsor his race. His determination alongside his experience out at sea made him an ideal candidate. Out of all the people rumored to be preparing for the voyage, Knox-Johnston was most likely going to be the winner.

Experienced sailor

Robin Knox-Johnston, a 28-year-old British merchant marine officer, realized a non-stop solo circumnavigation around the world was “about all there’s left to do now”. Knox-Johnston was born and raised in London where he joined the Merchant Navy in 1957-1968. He was an experienced sailor who was well-traveled for his age, but above all, he was determined to be the first to complete the race.

Built his own ship

Knox-Johnston built a 32ft wooden ketch with his friends in India, naming it Suhaili. The two-masted sailboat could be compared to a sloop, designed to perform well upwind.

Getting ready for the race

Two of his friends sailed the boat to South Africa, where Knox-Johnston would collect the ship and sail it single-handedly to London.

Bill King was another strong contender, as a former Royal Navy submarine commander, many thought he was going to cross the line first. He built a 42ft junk-rigged schooner and named it Galway Blazer. The ship was designed for heavy conditions and its rigging was designed to sustain strong winds.

The army couldn’t miss out either!

John Ridgway and Chay Blyth, two British army officers who also joined the race, had proven worthy in their 20ft rowboat in 1966. The two crossed the Atlantic Ocean and made it back all in one piece.

Rough oceans

Despite their rowing achievements, they were hampered by their lack of sailing experience. Adding to their issues, their 30ft vessels were designed for calmer waters and were not suitable for Southern Ocean conditions.

Bernard Moitessier

Bernard Moitessier was another recognized sailor within the community and was an experienced sailor in the Southern Ocean. His previous nautical expeditions had proven to be a success after his two books achieved international recognition. The French sailor had a custom-built 39ft steel ketch named Joshua for the race.

Donald Crowhurst

The most peculiar competitor in the race was Donald Crowhurst, a British businessman and amateur sailor who challenged himself by joining the race independently. Crowhurst was discharged from the Royal Air Force for unknown reasons, but would later start his own business named Electron Utilisation in 1962.

Born in India

Born in 1932, in Ghaziabad, British India, he experienced many hardships during his childhood. His mother dressed him like a girl until the age of seven, as she longed for a daughter. The family was forced to move back to England after facing severe financial problems in India, following the Partition of India.

A love for engineering

Crowhurst was a weekend sailor who enjoyed his ventures out at sea and was intrigued by electronics. He designed and built a radio direction finder called Navicator, a handheld device that allowed the user to take bearings on marine radio beacons. He mainly sold navigational equipment, but his business began to fail.

Sailing a trimaran

He decided to join the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race to revive his business. He aimed to build a fast ship that would accommodate a series of electronics to enhance the ship's voyage. Crowhurst designed and built a Trimaran for his voyage.

Grave financial situation

His main sponsor came from Stanley Best, who had invested heavily in his failing business. Crowhurst mortgaged his house and his business to continue his race preparation, placing him in a grave financial situation.

The race starts!

While most sailors began their race early in June, Crowhurst scrambled to set sail on the last day, the 31st of October. He encountered immediate problems with his boat, equipment, and his lack of open-ocean sailing skills caused him to make less than half of his planned speed.

Crowhurst's logs

According to Crowhurst's logs, he gave himself only 50/50 offs of surviving the voyage. The British businessman was sailing aimlessly around the South Atlantic for several months while the other boats sailed the Southern Ocean. He faced the choice of either financial ruin if he quit the race or committing to a race that might result in death.

Waiting game

While Crowhurst lingered around the Southern Atlantic, he would go on to write a 25,000-word manuscript in which he jots down thoughts and inner conversations with God around mathematics and logic. As the race continued, radio contact was less frequent, and Crowhurst entered a very negative mental state due to his isolation out at sea.

Bernard Moitessier dropped out of the race in March after facing strong storms in the Southern Ocean. The experienced French sailor was a strong contender for the race but was forced to sail back to Tahiti. Out of all nine sailors who started the race, only Knox-Johnston, Tetley, and Crowhurst were left.

All hope is lost

Knox-Johnston and Tetley were almost past Cape Horn, and into the final stretch of the race. Crowhurst's false reports drew the media's attention which only piled up more pressure on the inexperienced sailor. When reading his logs, one can sense Crowhurt's pressure and how he was on the verge of a tipping point.

Down to two

There would be no honorable finish for Crowhurst, as there would be no way of sneaking in 4th or 5th into the London docks. To make matters worse, the media claimed he was catching Tetley! This forced Tetley to push his boat until it broke down on the 30th of May, leaving Knox-Johnston and Crowhurst as the last two competitors.

Mental breakdown

Crowhurst reached his tipping point after eight months alone at sea. His writings depict a lonely tortured man, hinting at a serious mental breakdown.

Last log entry

Crowhurst ended radio transmissions on the 29th of June and his last log entry was July 1st stating: "It is finished, it is finished, it is the mercy." Teignmouth Electron was found adrift and unoccupied, on July 10th by a British Mail ship headed to the Caribbean. The boat now lies rotting in Cayman Barc after being refitted twice. Crowhurst, or his remains, have never been found and nobody knows exactly what happened to him.

312 days out at sea

Knox-Johnston was the only one to finish the Golden Globe race after 312 days out at sea. He spent five months passing the Southern Ocean, surviving a couple of series of scares onboard Suhaili. The British sailor was back to port by a large fleet of fans. He would go on to win the Golden Globe race alongside the $6,000 price, which he donated to the Crowhurst family.

20th century sailing icon

Knox-Johnston would go on to complete the same journey three more times before being knighted in 1995. He would go on to become a 20th-century sailing icon, still sailing today.

More for You

District attorney’s former lover withdraws from Trump’s election interference case

I'm abrosexual - it took me 30 years to realise

Diane Abbott refused to go on antisemitism course to rejoin Labour

Alligator twice the size of a man seized after being kept illegally in home

Emma Raducanu warns of ‘really bad’ problem in tennis as Iga Swiatek adds to her argument

Russian Volunteer Corps captured over two dozen Russian soldiers

Judge delays Donald Trump’s hush-money criminal trial for 30 days

Dentist reveals common mistakes people make that will ruin your teeth

Putin’s opposition know his election is a sham. They have a plan for change

Manchester United manager Erik ten Hag addresses Marcus Rashford exit

TV tonight: a gripping murder mystery with a beautiful New Zealand backdrop

How Ovo is driving its customers to despair

No room for Never Trump Republicans in US conservative media

Boeing plane loses panel mid-flight and pilots didn’t realise

Jimmy Kimmel's best Oscars 2024 jokes, from Donald Trump to Barbie snubs and Christopher Nolan

‘Your job is to referee the game’ – Heated exchange between Wales coach and referee during Six Nations clash

Rishi Sunak’s leadership on the brink following dismal polls and ministerial resignations

Sacked, reprimanded, and forced to resign: hundreds of judges censured for misconduct, new figures show

Former VP Pence says will not endorse Trump in upcoming election

Cancer breakthrough sees brain tumour almost disappear in just five days

- CLASSIFIEDS

- NEWSLETTERS

- SUBMIT NEWS

The Golden Globe Race is as tough as it gets

Related Articles

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

In 1969, or 2019, Sailing Round the World Alone Is Vexing

By Chris Museler

- Feb. 22, 2019

In 1968, nine sailors set out to compete in the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race, the first organized, solo, nonstop, round-the-world race. They were heading into the unknown, with no idea how their sailboats or their minds would cope with almost a year in isolation.

Some boats broke down, forcing them out of the race. Sailors crumbled under the emotional strain. One competitor, Donald Crowhurst , attempted to fake his circumnavigation, and then simply disappeared , abandoning his boat in the Atlantic.

Robin Knox-Johnston was the only finisher, returning on April 22, 1969, after 312 days at sea.

To mark the race’s 50th anniversary, another Golden Globe Race was planned. Organizers thought this one would be different, but the modern Golden Globe Race has proved to be no easier.

Last July, 17 36-foot sailboats departed from Les Sables-d’Olonne, France. Two sailors have made it back there for the finish. Only three remain racing ; one is still months from the finish line. Others abandoned their boats 15,000 miles away in the Indian Ocean and are still coming to terms with their dramatic ocean rescues.

“We haven’t had as many finishers as we thought,” Don McIntyre, a founder of the race and a circumnavigator, said.

The Golden Globe Race was created to promote ocean sailing for the average sailor, in small boats with modest budgets. Competitors are not allowed to use electric autopilots and instead use wind vanes for self-steering as in the first Golden Globe. Only radio communication is allowed; sextants are used for navigation.

Around 100 people have sailed solo, nonstop, round the world beneath the three great capes — the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, Cape Leeuwin in Australia and Cape Horn in Chile, the standard course for a solo circumnavigation. Many of these sailors have competed in the Vendée Globe, a solo round-the-world race started in 1989.

Unlike the high-speed, modern boats of the Vendée, which can outrun storms by sailing at speeds of 30 knots, the small, full-keeled Golden Globe boats are regularly overrun by depressions, especially in the Southern Ocean.

McIntyre said the 36-foot sailboats use modern masts designed to handle the impact of heavy ocean waves. Yet several boats in the race have been rolled or dismasted, most in the Indian Ocean.

Abhilash Tomy, an Indian Navy pilot, severely injured his back when his boat was rolled and dismasted halfway between the Cape of Good Hope and Australia, one of the most remote places on the planet. Another competitor was dismasted in the same storm, which had 70-knot winds and 45-foot waves.

Susie Goodall was rescued in early December after her boat went end over end and dismasted 2,000 miles west of Cape Horn. With her boat flooded and no engine or electronics, she called for rescue and was lifted off her foundering boat by the crane of a passing cargo ship.

Goodall has yet to talk publicly about her experience.

“Susie was in a desperate situation,” said McIntyre, who spoke with all the stricken sailors throughout the race to coordinate rescues. “She put her whole life into this. Then she’s picked up by the hook of a crane, and everything leaves instantly.”

McIntyre said he had spoken to Tomy about his accident and rescue, but “there were boundaries — it was too early.”

Mark Slats, one of the two sailors who has finished, said that the storms seemed to have no end and that the competitors looked to one another for support, a luxury Knox-Johnston did not have in the first Golden Globe.

“There was a real human aspect to the race,” said Slats, who tried to help advise Gregor McGuckin over the radio on handling his boat in large waves during a storm before McGuckin was dismasted days later. “We were really pulling ourselves through this together over the radio.”

McIntyre said many of the sailors were not mentally prepared for the isolation of the race.

“These sailors are coming from a different world than in 1969,” he said. “We are so used to being connected. This knocked some people out. It’s an amazing race, and if you’re not there for the right reasons, your mind will find a way to retire from the race.”

Those involved also said global weather patterns are producing stronger storms.

“I don’t want to hide behind bad luck, but the reality appears to be true, that the conditions in the Southern Ocean are changing and the weather is stronger,” McIntyre said.

Knox-Johnston, who now runs the Clipper Race, a round-the-world sailing race with stops for amateurs, said the effects of climate change could limit these types of races.

“We know with the heating of water, the atmosphere becomes less stable and there are more storms,” he said. “If we want people to cross oceans, we have to study this. Will things eventually be too unsafe weatherwise?”

Jean-Luc Van Den Heede of France, who has competed in several round-the-world races, won the Golden Globe trophy on Jan. 29, finishing in 211 days 23 hours 12 minutes. At 73, he is the oldest person to complete the course solo and nonstop, taking the mantle from Knox-Johnston, who was 67 when he completed the Velux 5 Oceans Race in 2007.

“Your mind is never the same after this,” Van Den Heede said in an interview the day he finished the race. “You learn to be an optimist, to take life as it arrives. Alone you have plenty of time to think, to look at your life. You don’t have time in the current life with pressures and meetings. Here you’re your own master.”

Slats, a 42-year-old Dutchman, finished three days behind Van Den Heede. He moved into second in the extreme cold of the Southern Ocean and came within 50 miles of Van Den Heede at one point in the North Atlantic.

“Sometimes I would drop a sail and have to go inside to boil water and warm my hands before rehoisting the new sail,” he said.

Despite the accidents, Knox-Johnston said, lessons learned from the race will benefit sailors.

“I’m talking to all the contestants as to why they were dismasted,” he said. “We’ve learned enough to make it safe for you to sail across an ocean. This will open up so many horizons. It’s got to be right. It’s good for our sport.”

Uku Randmaa and Istvan Kopar are expected to complete the race in mid-March. Tapio Lehtinen, who passed Buenos Aires in the past week, should finish in late June. All but Lehtinen, hindered by massive goose barnacle growth on his boat’s bottom, are expected to beat Knox-Johnston’s time of 312 days.

The Golden Globe Race is now planned for every four years. Though some of the boats in this edition were identical, the 2022 race will feature an open class and a class for replicas of “Joshua,” the bright red boat Bernard Moitessier sailed in the first Golden Globe. The Frenchman, after circumnavigating the world once, decided not to finish the race and kept going, landing in Tahiti.

Despite their accidents at sea, McGuckin and Tomy are still planning to compete in the 2022 race. McIntyre said there would be a maximum of 20 boats allowed, and 12 entries are confirmed for the next race.

Even Goodall said she was interested in racing again.

“Some people just live for adventure; it’s human nature,” she said in a statement after she was rescued. “And for me, the sea is where my adventure lies.”

You are using a very outdated website browser. Upgrade your browser or install Google Chrome to better experience this site.

Latest News: Fickle First Week for McIntyre Ocean Globe Race

days hrs mins secs

The Ocean Globe Race (OGR) is a fully crewed retro race in the spirit of the 1973 Whitbread Round the World Race. It marks the 50th anniversary of the original event.

It’s an eight-month adventure around the world for ordinary sailors on normal yachts. Racing ocean-going GRP production yachts designed before 1988, there will be no computers, no satellites, no GPS, and no high-tech materials. Sextants, team spirit and raw determination alone in the great traditions of ocean racing are allowed on this truly human endeavor. These will be real heroes pushing each other to the limit and beyond – in a real race!

Following the success of the 2018 Golden Globe Race , the concept of retro, fully crewed, traditional ocean racing around the globe has returned.

Don McIntyre – 8 minutes on ‘Who What How When Where and Why of the OGR’

Yesterday and Today

The 1968 sunday times golden globe race was the first ever around-the-world yacht race..

It was an adventure to determine who could be the first to circumnavigate the globe solo, nonstop without assistance. Nine sailors started, only one finished. It was an epic tale won by the least expected to win – Sir Robin Knox-Johnston in the 32ft timber ketch Suhaili . He established a world record in the same year that footsteps first appeared on the surface of the Moon. A few years later, the British yachting establishment organised the first ever fully crewed yacht race around the world. With backing from Whitbread Breweries and following in the wake of the great clipper ships, the legend that became known simply as ‘The Whitbread’ was born in 1973.

18 yachts lined up for the start on a sunny Saturday morning in Portsmouth England on 8 September 1973. Two more would join for later legs. It was an adventure, a family affair even, in yachts from 45ft to 74ft.

The race would take them first to Cape Town, South Africa and on to Sydney Australia, before heading deep south around the infamous Cape Horn to Rio de Janeiro and finally back up to Portsmouth – 27,000 miles later. A total of 324 crew were involved. Sadly, three would never return; lost overboard during Southern Ocean storms. Five yachts retired and three were dismasted. This race was also won by the least expected to win; a family crew with friends, sailing a standard production Swan 65 yacht, Sayula II , skippered by Mexican Ramón Carlin.

It was a fantastic race. A true adventure filled with real stories of human endeavour, colour and challenges on the high seas.

For the next 20 years the adventure continued with a Whitbread Round the World Race staged every four years. Sailors of all levels, ages and backgrounds were able to follow their dreams. They signed on and circumnavigated the globe – in a race.

Yachts became steadily faster, and costs began to climb. The fifth edition in 1989 saw one entry spend £6million in an unsuccessful bid to win. The 6th edition in 1993 brought huge change and sadly the end for most sailors hoping to be part of this ultimate challenge. By then, the Whitbread Race had evolved into a fully professional event. In the words of the organisers, it was now the Formula 1 of Grand Prix ocean yacht racing. Ordinary sailors with their dreams could only spectate.

A growing international audience, advancing technology and huge budgets led eventually to Volvo taking over the race. They transformed the event into a nautical extravaganza of stunning proportions with elite sailors that we have all grown to respect. Peak athletes all, sailing a few grand prix, state of the art, one-design yachts, driven by computers, all with comprehensive shore support ready to pick up the pieces. These spectacular Volvo yachts left the clipper ships in their wake in every sense!

Today, these high budget boats chase records across the planet to dazzle at race villages and big budget spectacles. Currently in a state of transition, the newly renamed Ocean Race is stepping up again, reinventing itself in exciting ways with IMOCA 60 yachts sailed by just five elite crew and autopilots now helming for the first time.

On the 50th anniversary of the original Whitbread Round the World Race, McIntyre Adventure (organisers of the Golden Globe Race ) and the Globe Yacht Club are proud to announce, that after 30 years of spectating, ordinary yacht club sailors and owners everywhere, once again have a chance to race around the globe! We are going back to that first great Whitbread Race and sailing like it’s 1973. The Ocean Globe Race (OGR) is for sailors with a dream and a sense of adventure – pure and simple! Is it YOU?

O°G°R Latest News

Technical Partners

Official suppliers.

Associations

You are using a very outdated website browser. Upgrade your browser or install Google Chrome to better experience this site.

Latest News: €213 Million Golden Globe Race 2022 Media Value

days hrs mins secs

× Why not try the live tracker on your phone? Click here for a video tutorial of how to download and use the app.

Title Partner

Major partners, premium partners, technical partners, les sables-d'olonne host port partners.

Associations

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The Sunday Times Golden Globe Race was a non-stop, single-handed, round-the-world yacht race, held in 1968-1969, and was the first round-the-world yacht race. The race was controversial due to the failure of most competitors to finish the race and because of the apparent suicide of one entrant; however, it ultimately led to the founding of ...

North Atlantic 1 July 1969. 1968 Sunday Times Golden Globe Race entrants. There was only one finisher - Robin Knox-Johnston and his 9.75m traditional ketch-rigged double-ended yacht Suhaili who, at the start, were considered the most unlikely boat and given no chance. The rest either sank, retired or committed suicide.

Donald Crowhurst. Donald Charles Alfred Crowhurst (1932 - July 1969) was a British businessman and amateur sailor who disappeared while competing in the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race, a single-handed, round-the-world yacht race held in 1968-69. Soon after starting the race his boat, the Teignmouth Electron, began taking on water.

Enter the Golden Globe Race, sponsored by the Sunday Times. It was 1968 and much of Great Britain was in a frenzy about sailing. Adventurer and millionaire Francis Chichester had just sailed his yacht, the Gipsy Moth, around the world by himself in record time the year before. Chichester came home to a hero's welcome.

In 1968, The Sunday Times Golden Globe Race was the first ever around-the-world solo yacht race. Known at the time as a voyage for madmen, lives were forever changed - yachts sank, a suicide occurred and of the nine entries only one man finished - Sir Robin Knox-Johnston becoming the first person ever to sail solo, nonstop and unassisted ...

The Sunday Times Golden Globe Race was a non-stop, single-handed, round-the-world yacht race, held in 1968-1969, and was the first round-the-world yacht race. The race was controversial due to the failure of most competitors to finish the race and because of the apparent suicide of one entrant; however, it ultimately led to the founding of the BOC Challenge and Vendée Globe round-the-world ...

The Return of the 1968 Sunday Times Golden Globe Yacht Race. Retro, Solo, Non Stop, Around the World. Latest News: €213 Million Golden Globe Race 2022 Media Value. ... The original sign and logo advertising the 1968/9 Sunday Times Round the World Race. Suhaili was a slow, sturdy 32ft double-ended ketch based on a William Atkins ERIC design. ...