Great choice! Your favorites are temporarily saved for this session. Sign in to save them permanently, access them on any device, and receive relevant alerts.

- Sailboat Guide

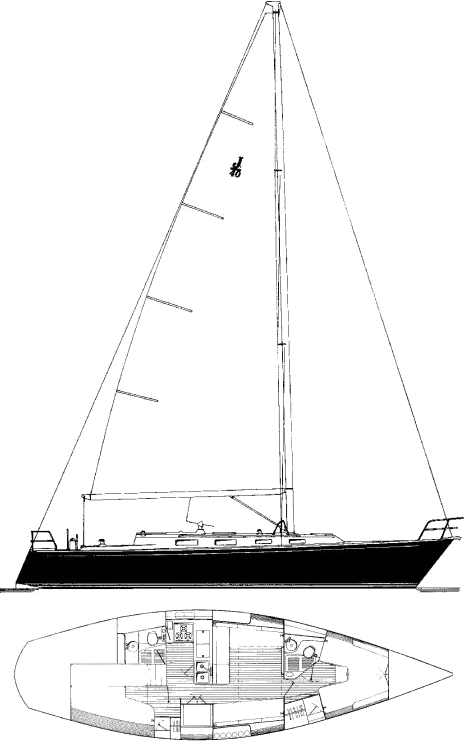

J/40 is a 39 ′ 11 ″ / 12.2 m monohull sailboat designed by Rod Johnstone and built by J Boats between 1984 and 1993.

Rig and Sails

Auxilary power, accomodations, calculations.

The theoretical maximum speed that a displacement hull can move efficiently through the water is determined by it's waterline length and displacement. It may be unable to reach this speed if the boat is underpowered or heavily loaded, though it may exceed this speed given enough power. Read more.

Classic hull speed formula:

Hull Speed = 1.34 x √LWL

Max Speed/Length ratio = 8.26 ÷ Displacement/Length ratio .311 Hull Speed = Max Speed/Length ratio x √LWL

Sail Area / Displacement Ratio

A measure of the power of the sails relative to the weight of the boat. The higher the number, the higher the performance, but the harder the boat will be to handle. This ratio is a "non-dimensional" value that facilitates comparisons between boats of different types and sizes. Read more.

SA/D = SA ÷ (D ÷ 64) 2/3

- SA : Sail area in square feet, derived by adding the mainsail area to 100% of the foretriangle area (the lateral area above the deck between the mast and the forestay).

- D : Displacement in pounds.

Ballast / Displacement Ratio

A measure of the stability of a boat's hull that suggests how well a monohull will stand up to its sails. The ballast displacement ratio indicates how much of the weight of a boat is placed for maximum stability against capsizing and is an indicator of stiffness and resistance to capsize.

Ballast / Displacement * 100

Displacement / Length Ratio

A measure of the weight of the boat relative to it's length at the waterline. The higher a boat’s D/L ratio, the more easily it will carry a load and the more comfortable its motion will be. The lower a boat's ratio is, the less power it takes to drive the boat to its nominal hull speed or beyond. Read more.

D/L = (D ÷ 2240) ÷ (0.01 x LWL)³

- D: Displacement of the boat in pounds.

- LWL: Waterline length in feet

Comfort Ratio

This ratio assess how quickly and abruptly a boat’s hull reacts to waves in a significant seaway, these being the elements of a boat’s motion most likely to cause seasickness. Read more.

Comfort ratio = D ÷ (.65 x (.7 LWL + .3 LOA) x Beam 1.33 )

- D: Displacement of the boat in pounds

- LOA: Length overall in feet

- Beam: Width of boat at the widest point in feet

Capsize Screening Formula

This formula attempts to indicate whether a given boat might be too wide and light to readily right itself after being overturned in extreme conditions. Read more.

CSV = Beam ÷ ³√(D / 64)

Draft-wing keel: 5.40’/1.65m Shallow draft fin: 5.00’/1.52m

Embed this page on your own website by copying and pasting this code.

- About Sailboat Guide

©2024 Sea Time Tech, LLC

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

- Types of Sailboats

- Parts of a Sailboat

- Cruising Boats

- Small Sailboats

- Design Basics

- Sailboats under 30'

- Sailboats 30'-35

- Sailboats 35'-40'

- Sailboats 40'-45'

- Sailboats 45'-50'

- Sailboats 50'-55'

- Sailboats over 55'

- Masts & Spars

- Knots, Bends & Hitches

- The 12v Energy Equation

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Build Your Own Boat

- Buying a Used Boat

- Choosing Accessories

- Living on a Boat

- Cruising Offshore

- Sailing in the Caribbean

- Anchoring Skills

- Sailing Authors & Their Writings

- Mary's Journal

- Nautical Terms

- Cruising Sailboats for Sale

- List your Boat for Sale Here!

- Used Sailing Equipment for Sale

- Sell Your Unwanted Gear

- Sailing eBooks: Download them here!

- Your Sailboats

- Your Sailing Stories

- Your Fishing Stories

- Advertising

- What's New?

- Chartering a Sailboat

- Cruising Yachts 40' to 45'

The J40 Sailboat Specs & Key Performance Indicators

The J40, a performance cruising boat, was designed by Rod Johnstone and built in the USA by Tillotson-Pearson.

Published Specification for the J40

Underwater Configuration: Fin Keel & Spade Rudder

Hull Material: GRP (Fiberglass)

Length Overall: 40'0" (12.2m)

Waterline Length: 34'0" (10.4m)

Beam: 12'2" (3.7m)

Draft: 6'6" (2.0m) - deep draft version, 5'6" (1.7m) - shallow draft fin keel version, 5'5" (1.6m) - wing keel version.

Rig Type: Masthead Sloop

Displacement: 18,000lb (8,165kg)

Designer: Rod Johnstone

Builder: Tillotson-Pearson

Year First Built: 1984

Year Last Built: 1994

Number Built: 86

Published Design Ratios for the J40

1. Sail Area/Displacement Ratio: 17.9

2. Ballast/Displacement Ratio: 36.1

3. Displacement/Length Ratio: 204

4. Comfort Ratio: 27.9

5. Capsize Screening Formula: 1.9

read more about these Key Performance Indicators...

Summary Analysis of the Design Ratios for the J40

1. A Sail Area/Displacement Ratio of 17.9 suggests that the J40 will, in the right conditions, approach her maximum hull speed readily and satisfy the sailing performance expectations of most cruising sailors.

2. A Ballast/Displacement Ratio of 36.1 means that the J40 will have a tendency to heel excessively in a gust, and she'll need to be reefed early to keep her sailing upright in a moderate breeze.

3. A Displacement/Length Ratio of 204, tells us the J40 is clearly a light displacement sailboat. If she's loaded with too much heavy cruising gear her performance will suffer dramatically.

4. Ted Brewer's Comfort Ratio of 27.9 suggests that crew comfort of a J40 in a seaway is similar to what you would associate with the motion of a coastal cruiser with moderate stability, which is not encouraging news for anyone prone to seasickness.

5. The Capsize Screening Formula (CSF) of 1.9 tells us that a J40 would be a safer choice of sailboat for an ocean passage than one with a CSF of more than 2.0.

More about the J40...

The J40 was designed by Rod Johnstone and built by J Boats between 1984 and 1993. It was the first bluewater offshore cruising boat built by J Boats, and it has a loyal following of owners who appreciate its performance, comfort and quality.

The J40 is a sloop-rigged boat with a fin keel and a spade rudder. The sail area is 765 square feet, which gives it a sail area to displacement ratio of 18. The boat is powered by a 43 hp diesel engine.

The J40 has a sleek and elegant hull shape that is optimized for speed and stability. The boat can handle a variety of wind and sea conditions, and it has a reputation for being fast, responsive and easy to sail . The J40 has also proven itself in offshore racing, winning several awards and trophies under the ORR and PHRF handicap systems.

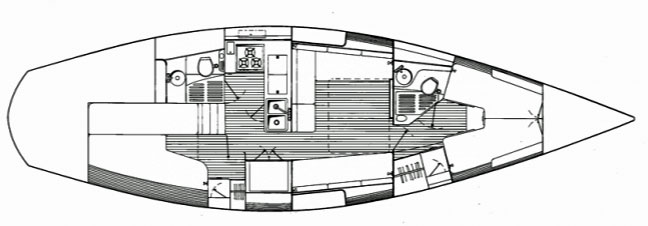

Accommodation The J40 can accommodate up to six people in two separate cabins and the main saloon. The forward cabin has a V-berth with storage underneath, a hanging locker and a private head with shower. The aft cabin has a double berth, a hanging locker and access to the second head with shower. The main saloon has a U-shaped dinette to port that can convert into a double berth, and a settee to starboard that can serve as a single berth. The navigation station is located aft of the settee, facing outboard. The galley is located aft of the dinette, along the port side. It has a three-burner stove with oven, a double sink, a top-loading refrigerator and ample storage space.

The interior of the J40 is spacious, bright and well-ventilated. It has large windows, hatches and ports that provide natural light and fresh air. The woodwork is made of teak, which adds warmth and elegance to the cabin. The upholstery is durable and comfortable, and the cushions are thick and firm. The layout is practical and functional, with plenty of headroom, storage space and access to the engine and systems.

Hull and Deck The hull of the J40 is made of fiberglass with balsa core for stiffness and insulation. The deck is also made of fiberglass with balsa core, except for high-stress areas where solid fiberglass is used. The hull-to-deck joint is bonded with adhesive and through-bolted with aluminum toe rail. The bottom is protected by an epoxy barrier coat to prevent osmosis.

The deck of the J40 is designed for safety and convenience. It has wide side decks, molded nonskid surfaces, stainless steel handrails and lifelines, and recessed hatches. The cockpit is large and comfortable, with high coamings, long seats, deep lockers and an integrated swim platform. The boat is steered by a single wheel mounted on a pedestal that also houses the engine controls, the compass and the instruments. The sail controls are led aft to the cockpit through organizers and clutches, making it easy to handle the boat single-handed or with a small crew.

The above text was drafted by sailboat-cruising.com using GPT-4 (OpenAI’s large-scale language-generation model) as a research assistant to develop source material; we believe it to be accurate to the best of our knowledge.

Other sailboats in the J-Boat range include:

Recent Articles

'Natalya', a Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 54DS for Sale

Mar 17, 24 04:07 PM

'Wahoo', a Hunter Passage 42 for Sale

Mar 17, 24 08:13 AM

Used Sailing Equipment For Sale

Feb 28, 24 05:58 AM

Here's where to:

- Find Used Sailboats for Sale...

- Find Used Sailing Gear for Sale...

- List your Sailboat for Sale...

- List your Used Sailing Gear...

Our eBooks...

A few of our Most Popular Pages...

Copyright © 2024 Dick McClary Sailboat-Cruising.com

The J40 is a 40.0ft masthead sloop designed by Johnstone and built in fiberglass by J Boats between 1984 and 1993.

85 units have been built..

The J40 is a moderate weight sailboat which is a reasonably good performer. It is stable / stiff and has a good righting capability if capsized. It is best suited as a coastal cruiser. The fuel capacity is originally small. There is a short water supply range.

J40 for sale elsewhere on the web:

Main features

Login or register to personnalize this screen.

You will be able to pin external links of your choice.

See how Sailboatlab works in video

We help you build your own hydraulic steering system - Lecomble & Schmitt

Accommodations

Builder data, modal title.

The content of your modal.

Personalize your sailboat data sheet

Weather Forecast

2:00 pm, 06/12: -11°C - Partly Cloudy

2:00 am, 07/12: -4°C - Clear

2:00 pm, 07/12: -7°C - Partly Cloudy

2:00 am, 08/12: -3°C - Overcast

- Cruising Compass

- Multihulls Today

- Advertising & Rates

- Author Guidelines

British Builder Southerly Yachts Saved by New Owners

Introducing the New Twin-Keel, Deck Saloon Sirius 40DS

New 2024 Bavaria C50 Tour with Yacht Broker Ian Van Tuyl

Annapolis Sailboat Show 2023: 19 New Multihulls Previewed

2023 Newport International Boat Show Starts Today

Notes From the Annapolis Sailboat Show 2022

Energy Afloat: Lithium, Solar and Wind Are the Perfect Combination

Anatomy of a Tragedy at Sea

What if a Sailboat Hits a Whale?!?

Update on the Bitter End Yacht Club, Virgin Gorda, BVI

Charter in Puerto Rico. Enjoy Amazing Food, Music and Culture

With Charter Season Ahead, What’s Up in the BVI?

AIS Mystery: Ships Displaced and Strangely Circling

Holiday Sales. Garmin Marine Stuff up to 20% Off

- Boat Reviews

J/40 Gryphon

About three years ago my wife Raine and I sailed our J/40 Gryphon down Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay under the Newport Bridge and south past Block Island. It was a fairly typical late season sail – blustery winds, scudding cumulus clouds, and chilly air – except that we never turned back. Now, 15,000 miles later, we’re sitting in Port Moselle Marina in Noumea, New Caledonia, having cruised the Caribbean, transited the Panama Canal, and crossed the Pacific.

Before leaving Rhode Island we had performed a fairly intensive refit of Gryphon, converting her from a weekend cruiser/racer into a blue-water, liveaboard boat. In the process – we added, we serviced, we rebuilt, and we replaced – nearly 100-plus projects, big and small, were completed. Altogether we felt we assembled a cohesive and sensible set of systems with which we could live safely and comfortably for some years to come.

Each of our decisions – my engineering background demands that I organize and categorize projects like these – fits neatly into one of two categories: “good” and, well, um, “other.” By describing some of the distinct winners and losers that hindsight now makes obvious as well as some generalizations based on our experiences, perhaps what we learned can benefit other long-term cruisers.

The first, and most far-reaching, decision we made was to do extensive open-ocean sailing in a J/40 – not the sort of boat that first comes to mind when people think of a liveaboard vessel. For us, it was – and still is – the right choice. Beyond the basic needs of safety, comfort, size, and budget, we wanted a boat that would be fun to sail. Gryphon has answered, and answered ably, in all of these categories.

There’s a single notable disadvantage to the J/40 as a liveaboard boat – a lack of storage volume. This means that the second cabin often becomes the repository for spare sails, bicycles, and other bulky items. We added storage space by modifying the aft berth, converting the centerline space to storage compartments and shelves, and by having a custom cabinet made for under the saloon table. And although the second head could be considered overkill, the two-cabin layout has allowed us easily and comfortably to accommodate friends during long passages.

THE TASK When we purchased Gryphon, she was fitted out as a weekend cruiser only. The electronics consisted of a VHF radio, radar, and sailing instruments; the GPS was dysfunctional. Three old gel-cell batteries were wired together and charged from an automobile alternator and regulator. The sail inventory seemed extensive at first but turned out to include two battered mains and several worn and worthless genoas. The words “ground tackle” would more accurately read as “dock lines.”

To convert Gryphon from a casual weekender to a safe and reliable floating home, we concentrated on making her sturdy and, to a high degree, easy to operate. Much of the refit took place at Warren River Boatworks in Warren, R.I., where their attitude of rugged and proper installations meshed exactly with our needs. Sturdy – as applied to both the equipment and the installation – implies reliability, an important characteristic when cruising beyond the reach of 1-800 service calls, and it means more time devoted to cruising, less to maintenance or repairs. Reliability also comes through redundancy, multiple pieces of equipment that can perform the same task independently. And operational simplicity suggests convenience and usefulness, without which equipment may go unused and thus be little more than excess ballast. Our mindset was, “Do it right, do it once.” Gear that we bought was high quality, or we found a way to do without it. A dodger, for example, that cannot stand up to the occasional boarding wave is worse than useless.

SAFETY SYSTEMS Certainly one area where reliability and ease of use is important is safety equipment. We discovered that the ORC Special Regulations provided handy guidance for the best equipment to carry and for specific safety improvements we could make to the yacht itself. The definition of a Category One race involves long distances offshore and requires self-sufficiency and preparedness for serious emergencies without outside assistance – exactly the conditions of blue-water cruising. These rules were born of years of racing involving countless boats and crews facing all types of conditions, and they have benefited from the hindsight of both success and tragedy – their purpose being to thwart the latter. We treated the rules as a checklist, and we feel confident in the results. Thankfully, I cannot testify to the worthiness of any of our safety equipment in extremis since we haven’t had to deploy any of it in earnest.

An important safety improvement that we made to Gryphon was the addition of storm ports to cover the opening portlights. The Bowmar ports on the J/40 are up to the task of keeping out spray or the occasional deck-washing wave over the bow, but the compression-gasket closure seems inadequate to stop a boarding wave that breaks against the coach roof. The storm ports are simple 3/8-inch Lexan plates that fully cover the portlights when attached. They are held to the coach roof by two bolts, one at each end, that are fastened to stainless-steel threaded receivers which in turn have been permanently mounted beside each port. Mounting or dismounting the eight storm ports takes less than ten minutes, and, having now been nearly knocked down by a breaking beam sea, we are convinced that these were a worthy investment for both comfort (never a leak) and safety.

GROUND TACKLE Ground tackle is a frequent topic of conversation among cruisers. Our choice is a 45-pound Bruce anchor with 200 feet of 5/16-inch, hi-tensile chain. The Bruce, which we used on a previous cruising boat and on several charter boats, has served us extremely well, and we’re still happy with our pick. Speaking honestly, though, a casual dock survey shows that the CQR (and derivatives) is the most popular anchor out there. The 200 feet of chain may be overkill – perhaps 150 feet would be sufficient – but anchoring in depths of 80-plus feet with plenty of scattered coral heads has been common ever since we sailed into the Society Islands. While we do carry two complete rodes on the bow, we could count on one hand the number of times that we used both anchors. A stern anchor would be many times more useful.

The windlass that we added is the Lewmar Ocean Two with gipsy and capstan. It has been 100-percent reliable (although the “waterproof” circuit breaker turned out not to be) and has required only minimal maintenance. It does have one significant inherent drawback that took us some miles to understand and circumvent – the hawse pipe is insufficiently protected from boarding seas and tends to ship large quantities of water. As Gryphon’s anchor locker drains directly into the deep bilge, this is a major disadvantage. Even on a boat with a watertight anchor locker, the amount of water shipped will damage quickly the electric motor and corrode the transmission and mounting. We fabricated a plastic-and-leather panel that is bolted in the place of the normal hawse cover and that completely seals the hawse pipe during offshore passages. Since we usually move the anchor off the bow during long passages anyway, it’s no additional inconvenience to close off the hawse pipe in this manner.

THE ELECTRICAL SYSTEM Most cruisers these days have hefty electrical requirements demanding large-capacity battery banks and charging systems adequate to the task. Gryphon is no exception with our PUR 80 watermaker and Glacier Bay 12-volt refrigeration system. The two house batteries are 8-D absorbed glass mat Lifeline batteries from Concorde. We have been very pleased with the operation of these batteries, including the sealed aspect of them and their high-acceptance charge rate. The two house batteries are normally kept electrically paralleled to provide maximum capacity. In the event of a battery failure, however, this redundancy allows the failed battery to be taken offline and the boat to be operated completely on the remaining healthy battery. Further redundancy is provided by a small maintenance-free wet cell, which is used only for engine starting.

We have four distinct means of charging the boat’s batteries – solar, wind, engine, and shorepower – all of which can operate independently and/or concurrently. Our assumption was initially that the solar and wind sources could produce sufficient energy to meet our daily needs. While this is probably true on average, it does not take into account the exceptionally high current drain of the refrigeration system (35 amps), and we have found that running the engine for the (roughly) 45 minutes per day required by the refrigerator satisfies that system’s demand and tops off any other accumulated deficiency. Other normal daily electricity consumption is usually offset by the solar and wind sources. That said, however, on a passage with a fresh breeze or in an anchorage in trade-wind conditions, the wind generator will produce a constant 10-12 amps and can easily keep up with all of the electrical needs. The equipment we installed is as follows:

• Solar – Siemens high-efficiency panels. Two panels are bolted permanently to the coach roof in a way that one is nearly always in full view of the sun, while the other may or may not be shaded by the boom. We chose to install the panels in a manner that would require no attention from us, especially in preparation for rough conditions. The trade-off is that our panels are not oriented optimally for maximum output, but, alternatively, they exhibit zero windage and have weathered all wind and sea conditions faultlessly.

• Wind – Fourwinds II generator. This generator produces high-current output, especially in trade-wind conditions (12-18 knots). The suggested benefit of some (small) output even at low wind speeds is superfluous in a system with loads like DC refrigeration and watermaker. The generator was purchased secondhand; the rebuild was simple, and the company’s service excellent. • Engine – Hamilton Ferris 120 amp alternator with Heart Incharge three-step regulator. Flawless. Operates as advertised. Need I say more?

• Shorepower – Heart Freedom 10 (combination inverter and charger). Ditto. While the 1,000-watt inverter output may seem excessive for a boat with no microwave oven or TV, it has been used innumerable times for power tools including a drill, sander, and heat gun. When traveling outside North America, 110-volt AC power is only available if we generate it ourselves.

A couple of noteworthy items regarding shorepower include, one, that we had to purchase a step-down transformer in New Zealand in order to use the domestic 220 VAC supply. It’s the same here in New Caledonia. If I were preparing the boat today I would include a transformer as a permanently wired component in the shorepower system. And two, every country (and sometimes each marina!) seems to have its own “standard” AC plug and socket. A 100-foot extension cord can be refit at each location with a local plug from an equally local hardware store.

Having mentioned a couple of the significant DC loads on the boat, I should elaborate that both the Glacier Bay DC refrigeration system and the PUR 80 watermaker have performed well for the past three years. The refrigerator, in particular. It was switched on in Rhode Island in October 1998 and not switched off until our short haul-out in New Zealand in November 1999. The PUR 80 has accumulated over 1,000 hours of operation with consistently excellent results. I recently serviced the pump, replacing the seals and changing the gear oil (a normal 1,000-hour requirement), and was particularly impressed with the thoroughness of the PUR documentation and the ease of the service procedure.

Finally, a few generalizations with regard to the electrical system:

• Electrical demand only rises. In my observation, most people only add or upgrade equipment during their cruising tenure and electrical demand only goes up. Plan for spare capacity initially.

• Systems with DC motors are less efficient at lower voltages. Quoted production rates are always given for some specified operating voltage that is often the higher voltage seen only during charging. Running on batteries alone will reduce output below specification. Plan accordingly.

• While we never expected to spend significant time at docks, we have done so during the South Pacific cyclone season in New Zealand and now in New Caledonia. A DC-powered refrigerator has turned out to be an apparent (albeit quite circumstantial) stroke of genius. While other cruising boats endure the noise and smoke of engine-powered systems, ours just hums along on demand directly from shorepower (via the charger and batteries).

ELECTRONICS Here is a category that will undoubtedly engender strong opinions and reactions. I’ll limit my discussion to only two systems – the biggest winner and the biggest loser. When we purchased Gryphon, she already had a basic Nexus instrument system, consisting of windspeed, depth, and speed transducers, and two multifunction displays. Given this base we chose to elaborate on the system and added displays, an integrated autopilot, and a GPS interface. After some initial problems with autopilot/instrument software incompatibilities, the system has turned out to be incredibly stable and convenient.

A J/40 is commonly steered by sitting outboard at the helm. At each of these positions we have one multifunction display. There is a third display above the companionway in sight of the helm and everywhere else in the cockpit. The beauty of the multifunction display has been that the most pertinent data can be displayed in a manner that is most effective for wherever the helmsperson is situated, whether that be at the helm itself or elsewhere in the cockpit while the autopilot drives. If sailing on the wind, or perhaps downwind, wind angle can be prominently displayed. When sailing on an easy reach, navigation data (bearing to waypoint, cross-track error) can be shown. While navigating in soundings, depth can be shown. In each case the helmsperson can decide which information is displayed where and can easily cycle through the entire suite of data.

Belowdecks at the chart table, a Nexus remote control provides total access to the instrument data as well as control of all system operations – including the autopilot. The remote is on a long cord that allows the helmsperson to move to the companionway in the protection of the dodger and still steer. The Nexus system has turned out to be a delight to operate and in every way has met our needs.

On the other hand, every mariner has his or her albatross and ours is a SGC 2000 single-sideband radio. Our first bad experience with the radio occurred less than six months after installation when the transmitter failed in the Caribbean. It was there that we discovered that SGC’s “No compromise” warranty was limited to the United States and that we would have to pay the not inconsequential shipping charges to and from St. Maarten. SGC’s explanation for the failure was simply “component failure” and that it was in no way related to usage or installation.

I understand fully the meaning of statistical data, and anecdotal examples should not condemn completely. Yet, since our problems with this radio started, I’ve made a point of questioning every SGC owner that I come across regarding the reliability of their radio. Without exception each owner has had to return his or her radio at least once to the factory for servicing. A few additional, random discoveries that we’ve made over the past 15,000 miles:

• You can never have too many tie-down points on deck. • You can never have too many lights. • You can never have too much shade in the tropics. • A stern arch will accommodate a dozen additional items initially forgotten. • Leaks suck. • Big lures attract big fish. •And, finally, in big bold print, underlined, and embossed – Know Thy Systems.

Cruising aboard Gryphon since October 1998 has been delightful. We have entertained friends and family on short passages and on long. We have met some wonderful people, made friends for life, visited exotic islands and anchorages, and, just in general, made a life of this lifestyle. We give a lot of credit for our pleasure to Gryphon – her heritage as a J/Boat, her solid construction by TPI, and our own attitude of reliability and low-maintenance throughout the fitting out process – and we look forward to more pleasure-filled years cruising and exploring. LOA 40’ 4” (13.0 m.) LWL 35’ 0” (11.3 m.) Beam 12’ 2” (3.9 m.) Draft 6’ 5” (2.1 m.) Displ. 21,000 lbs. (9,545 kg.) Ballast 7,500 lbs. (3,409 kg.) Sail Area 733 sq. ft. (24.4 sq. m.) SA/D 16.2 D/L 219

Author: Blue Water Sailing

Leave a reply cancel reply.

× You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

We Ship Worldwide! | FREE SHIPPING! for US Continental orders over $99. Click for details.

Shopping Cart

Your cart is currently empty..

FREE SHIPPING! for US Continental orders over $99 click for details

J/40 - Sailboat Data, Parts & Rigging

Sailboat data, rig dimensions and recommended sail areas for J/40 sailboat. Tech info about rigging, halyards, sheets, mainsail covers and more.

Sailboat Data directory for over 8,000 sailboat designs and manufacturers. Direct access to halyards lengths, recommended sail areas, mainsail cover styles, standing rigging fittings, and lots more for all cruising and racing sailboats.

MAURIPRO Sailing offers a full range of sailboat and sailing information to help you find the correct sailboat part, one that properly would fit your sailboat and sailing style. Our sailor's and sailboat owner support team are ready to talk with you about your specific sailing needs, coming regatta, or next sailing adventure.

From all at MAURIPRO, let's Go Sailing!

Copyright © 2024 MAURIPRO Sailing LLC.

- Forum Listing

- Marketplace

- Advanced Search

- About The Boat

- Boat Review Forum

- SailNet is a forum community dedicated to Sailing enthusiasts. Come join the discussion about sailing, modifications, classifieds, troubleshooting, repairs, reviews, maintenance, and more!

J-40 for Long Distance Cruising ?

- Add to quote

I haven''t seen much discussion on this forum re J40 and it''s long distance potential. I notice that "Gyrphon" is currently listed for sale after a fairly quick circumnavagation. My initial thinking is that J40s sail very well, should be well constructed but lack needed storage. The admidship head could be converted into wet locker/storage pantry while keeping the actual head for seagoing usage. Does anyone have experience with a J40 in a seaway. How is the motion, do they sail on their ears, do they pound up-wind, etc? Is there an issue with the rudder bearing? Would greatly appreciate any input on these issues as well as current thinking for a short handed boat in the 37 to 40 range that can sail yet hold up to the rigors of long distance cruising.

not alot of help but i believe that there is a J-40 in this month''s Soundings Magazine that is for sale that has recently completed a multi-year cruise. You might want to speak with the owner regarding his/her experiences.

D, GYRPHON is only one example of J40''s used for extended cruising. There''s a J40 website with some useful info on conversions and construction issues that I''m sure Google will produce; sorry that I don''t have the URL handy. Still, it''s a relatively small volume hull and I think load carrying and storage issues, as you mention, would be one of its liabilities. E.g. we saw a J40 that was being cruised down in Bequia. Because the crew had decided that the boat absolutely had to have all the ''normal'' cruising gear (acres of canvas, solar panels, wind generator, wind surfer, on-deck jug farms due to its limited tankage, and oodles of other gear), it was down on its lines and looked like it had horrid windage. It seemed to me at the time the choice of the boat was made well before decisions about what the crew thought they needed from their boat. Jack

Since the introduction of the J-40 I have always viewed these boats with a mixed emotions. There is a whole lot about these boats that I really love. They sail well and have a very workable deck plan. They have a simple but nice interior layout. They are reasonably easy to handle in a wide range of conditions although I would prefer a fractional rig for offshore use. From my perspective, they represent a good compromise between performance and comfort. But if used for extended cruising they need to be pretty extensively adapted. As they came from the factory they lack adequate water supplies, seaberths and gorund tackle handling gear for example. Boats like the J-40 need to be viewed differently than is popular when thinking about distance cruisers. Extended cruising in a boat like the J-40 requires a very different mindset. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, if you size the J-40 by its a 16,700 lb displacement, this is a pretty small boat. In other words distance cruising in any 16,700 lb boat whether it is 32 feet or 40 feet is bound to be a little spartan. There is only so much payload weight in gear and supplies that a 16,700 lb boat can carry. You do not have the luxury of carrying anything that you might want to drag along. You do not have the luxury of carrying the kind of fuel supply to have ''all of the comforts of home''. It means that you have to be willing to limit the amount of gear and stores that you bring aboard. This is not so much a short-coming of the boat as it is a decision that one makes about what is important to them. The only other gripe that I have about the J-40 is that they just were not all that robust and I would want to beef up the rudder/rudder post, keel sump and transverse framing. Jeff

Thanks for the feedback, especially so as from Jeff. My previous voyaging was on a heavy 32 footer, with about 40 gallons of water, sextant, timex quartz ch., 2 burner kerosene stove and small poorly insulated icebox. I can get by without most of the current goodies, but don''t know if I can leave the windsurf board behind.

D, there''s another way we can look at the J40 if we''re willing to ignore the price issue. For a 9 ton boat (fully loaded, provisioned & equipped), it''s fast, easily sailed and with a functional layout that''s open, airy & suitable for a tropical environment. As Jeff suggests, when prospective buyers compare it with other 40 footers, they may find storage and tankage significantly smaller and they may wonder where they''ll be putting their huge collection of systems & add''l hardware. But when compared to most 8-9 ton boats, it''s probably a better performer while carrying the same load, and more comfortable as a home. And so we once again get to the nub of the issue, which is more about you, what you want out of the boat (performance vs. systems/cabins/tankage), and where you intend to do your cruising. If you can live comfortably on 100 amp/hrs/day, avoid the 5 gal. shower and invest the time and effort to provision thoughtfully and without carrying along the butcher shop from back home, this boat is more than adequate to the task re: volume. It may just cost more than many 8-9 ton boats. Jeff brings up a good question about the rudder and its bearing & structural set-up, and as I recall GYRPHON had to replace their bearing while in SoPac waters. All these boats with spade rudders can see a huge loading at sea in a blow. I''m not sure how feasible it is to strengthen that further, altho'' a call to TPI and/or J Boats would be a good idea if you get serious about this boat. Jack

The J-40 is a cruising option that has appealed to me as well. Jeff and Jack have both touched upon the subject of boat selection criteria, which is a multi-faceted equation that must be understood and calculated by each sailor individually. Most of us view boats by length overall. No less an authority than Steve Dashew has recommended purchasing the longest boat you can afford, reasoning that waterline length has the most impact on speed and comfort as well as safety. The J-40 is demonstrably fast, relative to nearly any other cruiser its length. It has an easy to handle sail and deck plan which includes a large powerful mainsail with traveler and sheets located handily for the helms-person. It has an easily driven narrow beam hull form, which I suspect would contribute to reasonably comfortable motion characteristics, except for heel angle and tenderness which they have been accused of, especially in shoal draft versions. Here the compromises of the selection process begin to arise. It has been rightfully pointed out that space for equipment and provisions is limited relative to boats with larger volume hull forms. Loading up this 17,000# sailboat will have greater impact on performance than it would on a heavier displacement vessel. If another boat is examined with a larger volume hull form, a wider beam and/or fuller sections will cause displacement to go up along with wetted surface area. In order to achieve anything like the performance of a J-40, sail area would then have to be vastly increased and handling of the greater loads will become a bigger chore. Ultimately, this vicious circle simply produces a bigger boat. Even if it remains 40’ LOA, it ends up 20,000#, or wherever you wish to call it quits. It is a logical and preferable alternative to primarily select the displacement first of the sailboat one is comfortable handling, given individual crew constraints and sailing intentions. Considering all available 17,000# sailboats to take cruising, the J-40 must be considered near the top of the list in my view. Certainly there are numerous other factors to consider such as those pointed out by others, and it may be determined that a larger displacement vessel is needed to provide the desired comfort and capacity, but if the alternative is to choose a boat of shorter length at the same displacement it is doubtful that much increase in comfort or capacity will be achieved. There may well be more recent design developments that improve upon the sailing qualities, durability or accommodations of the J-40, but then the cost element is also introduced. Newer boats usually cost more. If they don’t then we must look hard to find out how they achieved cost savings, why they are less well regarded, and what are the other trade-offs. Here we must compare boats of a given price and displacement. Displacement has traditionally been considered to have a greater impact on price than length does anyway, though they are inseparably related. Ballast ratio, construction and hardware technology, power resources and tank capacity all literally weigh into this, making the value factor the most difficult element of the boat selection equation to calculate, especially as it is compounded by differences in individual priorities. Sorry for the long winded commentary. Since I am no mathematician, this has probably resulted in no solution, but it’s a subject I’ve been thinking about as you see. I personally think the J-40 is a reasonable alternative if you like a boat for going places and sailing well too, which is all I needed to say in the first place. -Phil

Hi there, we sailed our J-40 Argonaut from SF to Sydney in 2003. To make it short, I loved the boat. The rudder bearing did go out on us, and I had to replace it in Hawaii. Wasn''t fun (or cheap). She will outsail most anything you come up against, handles BIG seas fine, goes to weather very well (which we did much more than I ever expected). We did convert the fwd head into storage. Also, the lazarette holds oodles of stuff. We had 5 headsails and 3 chutes with us (no furler on purpose). If you dropped one or two of the headsails and 1 or two of the chutes, you''d have plenty of stowage. Having all these sails, though, permitted us to do the crossing with around 40 gallons of diesel, start to finish (the tank holds about 33 gallons). We had no gerry cans, so what was in the tank had to suffice. ...Chris

Chris, thanks for the first-hand comments...which are always more valuable than we arm-chair commentators. I''m hoping you could follow-up by offering your answers to two key questions raised in the other posts: 1. What was your boat''s actual fully-loaded/equipped displacement when making your passages, as compared with the 16,700# design displacment quoted above? And how did you find that add''l load affected her sailing abilities (when, how much - to give us a sense for how the boat dealt with the weight abuse, whatever it was)? 2. Along with the rudder bearing, were there other signs of structural issues with the boat? Or were your passages such that there really wasn''t any opportunity for those to show up? Thanks for whatever (add''l) light you can shed on this discussion! Phil, I liked how you expressed several of your points. My reaction is that Dashew''s expressed view that one should consider length as the ''primary criterion'' is pretty typical of what surfaces in an ''expert book'' when the writer ends up being theoretical more than realistic. The real world ''pimrary criterion'', and one Dashew probably wouldn''t quibble with except around the edges, would better be stated something like ''longest boat that meets minimum structural requirements for the money you have to spend''. This is as opposed to the most length you think you can handle, or the most features offered by the length, or the most systems that can be comfortably placed and serviced on the boat - all of which seem to end up being competing criteria by the boat-as-RV cruising contingent. Good discussion. Jack

Hi Jack, not sure how much we loaded her down - it was about 1'''' at the waterline. We were used to racing the boat (no furler, peels for sail changes), and the fingertip control of the absolutely phenomenal steering-setup the J40 has. This fingertip control, by the way, holds true as much in 35 or 40 knots of wind (and seas) as in 10-12 knots. If not, something''s wrong with the trim setup. Makes it of course easy for the autopilot. Now we went for a testsail after loading the boat completely the first time, and I just about broke down crying. Sluggish, difficult to keep in a groove (still better than most boats, but nothing close to her potential). We had 300'' of chain and a bruce 45 on the bow. So we cut the chain into 2x120 + 1x60 feet, spliced 3strand to the 60 feet, and kept that on the bow, while moving the 240'' amidships. It''s hard to describe the huge difference this made. So for every passage we''d switch to the short-chain version, and the connect a 120'' section in once we had made landfall. The one time we didn''t do this for a passage, I regretted it. BTW, I believe that LOTS of cruisers suffer from way to much weight in the bow. When we were making landfall in Australia (part of a loose ralley), we were in our 3rd front of the passage, and doing 7+ knots beating into the seas (~55 degrees apparent) in the high 20''s/low30''s windwise. The boat was well balanced (reefed, #4 jib), and I was having fun as we rode the waves. Now this other boat we passed very quickly would climb up a wave, then the bow would smash down the backside, submerge, the next wave washing over bow and deck, and pretty much completely stopping the boat. Then slowly, he''d gain speed again, just to climb up the next wave, crash/submerge/and stop again. This all under power, because with sails alone he didn''t have the strength to fight the seas. On the VHF he was wondering what kind of amazing engine we had ;-). So I think that weight distribution is maybe even more important than total weight. BTW, this guy it turns out had 500'' of chain in the bow. I guess a fundamental question to ask yourself is do you like to sail, or to hang out at anchorages with lots of stuff. The two are nearly incompatible, unless you are amazingly wealthy. Just know that you''ll have to trade off one for the other. In regards to structural strenght on the 40, we didn''t have any problems, despite repeatedly beating into nasty waves. Off Samoa we kept on launching off waves an crashing down so bad that everything just shook to the bones. In that case, we reduced sail and slowed down, which fixed the prob. But no structural stuff. Only creeks we had were under the staircase. I had re-located the batteries there from the lazarette to center the weight better, and should probably have strenghted the thin ply-wood a bit before doing that (that section just wasn''t conceived/built as a battery compartment - did help with the weight distribution though ;-). ....Chris P.S.: I''ll be giving a talk about our trip at a SF Bay area yacht club in January, so if anyone''s interested, mail me at [email protected]

Are you saying that you used 40 gals of fuel from SF to Sydney? How many days did you spend on this trip? What did you use for self-steering/auto-pilot? Paul

I am not sure how relevant this is to your question, when I was researching my boat I exchanged email with a fellow who single-handed a Farr 11.6 (Farr 38) from South Africa to the Carribean (a much shorter trip). The boat was set up with a windvane and minimal electronics. He said he came up on one tank of fuel (something less than 17 gallons). Of course that kind of low fuel useage is only possible with the absense of refrigeration and electronic autopilots. He thought that his biggest draw was running his tricolor at night. Regards, Jeff

Chris, thanks for the informative, lengthy reply. Neat info and a good reminder for those of us who prefer all-chain rodes, too. Jack

Great post Chris. Many sailors forget the fact that boats behave quite differently when loaded and that the balance of the load out can be critical to her motion at sea. Carrying too much weight on the bow is typical and your example is very helpful. Recently was aboard a 36'' cat someone was cruising and living aboard. It was loaded up with so much that its waterline was 3 inches higher. That basically killed any performance gain. Higher displacement boats have a greater carrying capacity. That is one advantage. Given all the high tech gear we have today though ....smaller electronics, multifunction electronics, ultra light cold weather and foul weather gear, better designed ground tackle....cruisers who need to can lose a lot of the weight. It all adds up. Best John s/v Invictus Hood 38

John I think that is only partially true. In a general sense, I would think that the payload that any boat can carry in supplies and gear before it begins to lose performance is generally in a range somewhere around 15-20% of its overall displacement. That is true even of very light race boats which will often carry that much in crew and spare sails. (Think of a 14,000 lb 40 footer with a 9 man crew and all of their gear.) If you compare a longer boat with the same displacement as a shorter boat, the longer boat will have much greater carrying capacity with smaller impact on performance than the shorter boat. Even if you compare equal length boats, the lighter boat may lose more of its ultimate speed advantage but it still may be faster than the heavier boat when each is carrying the same payload. Respectfully Jeff

Hi Jeff Good point on boat length and performance. I agree. LOA and LWL being equal, the boat with the greater displacement should have a greater carrying capacity. Displacement being equal, the boat with the greater LOA or LWL should be able to carry more. I was really trying to address the issue of overloading. Many cruisers I have witnessed recently are carrying tremendous amounts of...just stuff. Every possible electronic, more ground tackle than the titanic as well as all the comforts of home with a nice heavy genset thrown in. The result is more and more boats being used as barges and not sailing vessals. I understand the reason for this, to each his own. But...in my mind, I think a lot of the ''stuff'' is needless and wasted. Much will hardly ever be used, much could be replaced perhaps even less expensively with more modern, lighter equivalents. I do think many of us in this forum in particular are alike. No matter whether we cruise or not, we got our boats because we want to sail them. I believe one can and should reasonably match the load out requirements to the performance parameters of the given vessal (not just take a given vessal and load it up without regard). People should give this thought to this as they do route planning etc. The J/40 issue might be a good exemplar. Here is a boat made for sailing. A pleasure to sail. It can be loaded out for reasonable cruising but overloaded, it becomes the leaded pig that any boat will. There are two more attractive alternatives. Either plan the fitting out and loading out with careful consideration as to weight carried. Or get a boat more suited to being loaded down. It is essentially the same thing as making an energy budget. Everything you could think of taking on a boat has specs you can look up. Look forward to chatting with you soon. John

I very much agree with you about the idea of picking a boat that will meet your needs in terms of what you personally need aboard. That is at the heart of my arguement for sellecting a boat by the displacement that you need. Weight only breeds more weight so unless you have an idea about how much weight needs to come aboard, it gets harder to achieve performance as more stuff creeps down below. Looked at another way, you pay a price for performance in terms of either going a little spartan for given length and lighter displacement, or else going longer to get the comfort and performance. There is nothing worse than sailing a boat that is way overloaded in terms of decreased motion comfort, seaworthiness and performance. I also like your point about the an energy budget. All to often you see boats that are compromised by the fuel cans lashed to the deck and bilges and lockers filled with spare tanks syndrome that comes with stuffing too many comforts of home into too small an envelope. Regards, Jeff

Yep, I am saying 40 gal for roughly 8000 miles and 9 months worth of cruising. Basically, with the tank holding 30 gallons (roughly 250 mile range), you don''t turn on the engine when you are becalmed on a 2000 mile passage, because it really wouldn''t help anyhow. So you use the engine to get into and out of anchorages. Even then, we tried often to sail in/out, just to keep in practice. Having light-air sails, and doing frequent changes, is part of the game though in this case. You might wonder why we did this. Here''s a short story to illustrate. We were loosely part of a HAM net. At one point, the engine of this particular boat died, while at anchor. So he is sitting there for days on end, and can''t get out, because its either blowing to hard and he''s worried about the reefs at the entrance, or it''s not blowing enough (and he''s worried about the reefs at the entrance). Now to make matters worth, when it''s blowing really hard, he gets injured (literally the coat-hook in the eye thing), and he still can''t get out. Finally, someone else sailed to the anchorage and towed him out. Then he caught a flight to Australia to have his eye looked after (the anchorage was, I think, in Papua New Gunea) - it all turned out well. For me, this gets at two things: boat''s too heavy to sail in light air, and many sailors stay comfortable and don''t push themselves to the edge (my wife and I had more than one friendly argument about sailing into tight spaces, until this ham-net thing unfolded real-time for over a week with us watching)

John, Jeff & the Group: I sure wish the recent discussion you two are sharing on how a boat is equipped, energy budgets, and how it sails had a higher visibility in the long-term, long-distance cruising venue than it does. Simply put, it''s just very common to find overloaded boats in today''s anchorages, and I''m convinced that in most cases the owners/crews really don''t have any concrete notion of how their boat''s sailing qualities have been incrementally effected. And the issue isn''t just ''weight'', either. The windage inherent in a dodger, bimini, weather cloths, easy-drop mainsail cover, radar arch, solar panels and jug farm(s) looks to my eye like it not only spoils the inherent aesthetic appeal a boat may have (''tho many cruising boats seem to be built ugly) but this windage must surely retard sailing ability to windward significantly. (Jeff, have you ever seen any empirical data on this in your design work? It would be interesting to know if it were quantifiable in some way). I have noticed this incremental degradation in performance becomes noticable when Ma & Pa Kettle return from their Caribbean Thing, offload the boat to the point where it''s ready to be sold, and then they do a sea trail with a prospective buyer or daysail her for fun. Oh Lordy, are they surprised... That SSCA Panel I was on this year, if I didn''t mention it before, was a real eye opener: 6 panel members representing 5 boats, all of whom had crossed at least one ocean and been out for some years now. The average boat, WHOOSH excluded, was 45'' LOA, between 16-20 tons (yet in each case, only 2 crew), ''needed'' 250-300 amp/hrs/day in DC consumption, had every system known to the CW advertising staff, had 2 dinks and 2 outboards (''one might break, you know...'') and of course every conceivable kind of canvas. Most had generators. As the panel began, I hadn''t thought of Patricia and I as the ''minimalists'' in the group; after all, we make big/clear/hard ice cubes, get real-time wx info and do email onboard, use lots of electronic thingies and have what we consider all the comforts of home. Hah! When I mentioned we used 70-80 amp/hrs/day and haven''t so far needed a water maker, eyes rolled and we might as well have been Lyn & Larry Pardey. John''s caution about selecting a boat that''s not going to be *too* overburdened by a given crew, given each crew''s own tastes in systems and personal effects, is right on...but there are several reasons why I don''t think it occurs often. First, folks start out with little experience and so can''t imagine the loading issue being as significant as it is. Second, systems (and also sheer boat junque) are acquired incrementally, without a thought about their collective impact. Third, boats are viewed as RVs these days, with the entitlement notion that a boat really should provide all the comforts of a condo simply because it can. Fourth, I wonder how many of us actually like and seek out good sailing, when our motivations are often in other areas. And I suspect the biggest reason is represented in the old saying ''The best boat to go cruising in is the one you have'' and so folks make do with what they have, and just ''load her up''. I remember when we were in the shopping mode that led us to WHOOSH (a Pearson 424 ketch), I used Dave Gerr''s Nature of Boats and estimated the #/inch immersion measurement for her - it was roughly 1 ton, which I liked. Even so, one of our winter projects while in our berth is to - once again - pull every single thing out of every locker and see what we can whittle down or eliminate altogether. (It felt very silly to be out sailing this past summer with a dehumidifer bubble-wrapped and tied down in the forward cabin). When flying home for the holidays, our bags were loaded with only one change of clothes but we sure had a lot of boat ''stuff'' in there. Without consistent effort, the weight just keeps getting added...much like what happens to all of us around the holidays. <g> Jack

Jack and Jeff, I think those were two very very important posts. Hope many will read carefully more than once. Jack - glad you are back. You raise many important points. Cruising boats have gotten larger...for a certain segment of the cruising world. It is something that is getting some press and enters into the long debated topic of what is the perfect boat. This in itself bears another topic thread for some lengthy discussion. As Jeff points out, you pay for capacity one way or another. A larger boat means more expense, much much more work, heavier mainsail to haul, heavier ground tackle etc etc. A smaller boat can take less without encountering its own penalty. Case in point. I sailed a boat similar to mine in FLA once. The owner was a liveaboard and had fit the boat out for convenience at the dock and not sailing. He made up some monster davit/arch setup for the stern himself. Unreal. And then hung everything you can imagine off of it. RIB, outboard, TWO wind gens, solar panels and radar. Unreal. We sailed and the heeling moment of this boat was almost scary. I really felt that the owner had created a potentially dangerous situation for cruising. Sailing a sistership in Annap later that was set up for serious cruising...with sailing in mind...was a completely different experience. They could have been two different boats. It was a good lesson. The same boat with a rib on nicer lighter davits (which are also lower to the water), ob hung on the transom, two newer (lighter higher capacity) solar panels fitted to the bimini, no wind gen and radar off the backstay sailed just great. In fact, at the risk of being prideful, I will say that SAILING this boat ...for me at least...is the thing that adds joy to cruising (that and my new sea kayak :O). There is no perfect boat. There are plenty of choices, however. Each optimal for a different approach. Great discussion. My best to all John s/v Invictus Hood 38

Great forum. I am new here. I agree with that. Ocean crossing with a j40 certainly would be fast and uncomfortable, and you would have to travel light, even if the boat has an AVS that gives tranquility. Not a family boat, or a living aboard, unless you live alone and are a sportsman.

I think that''s a pretty impressive feat - you must have been a real tight-wad on the engine use*g* You must not have had to use the engine to charge the batteries much. What type of wind vane steering did you use? How well did it drive down wind? I assume you had no refrigaration and didn''t use the auto-pilot much? My J/37 has about 25 gals fuel (close to 290 miles) and currently has a larger holding tank than a fuel tank. I''ve been considering replacing some of the holding tank with a 2nd fuel tank to avoid having tank farms on the deck. Not sure how much fuel I really want to carry. Paul

Have you ever sailed on a J/40? It isn''t spartan or uncomfortable. Paul

why is it that some folks always seem to generalize fast with uncomfortable. I would rather miss some clutter on the boat and go full out ( whatever that means) than to sit like a duck with all the crap on board swinging in the waves ... There are pages of pages very well written stuff in front of that post. And than comes something like this....... Thorsten J 30

No, but I have sailed some cruiser-racers that are not very different in shape and performance. Don''t get me wrong, I like the J40 a lot, and I even would have fun doing a fast and sporty oceancross in it, with a competent crew. But for cruising with the family it is another matter. I am sure I would have a lot of complaints, cause what is fun for me is (unfortunately) not fun for my family. I am talking not only about not having regularly fresh water baths, but also of a significant heel of the boat, of the fast pounding against the wind, with water flying around, I am talking about taking care alone of those big sails. Yes, like a lot of families, they are there for the sun and the beaches, I am there cause I like to sail, so they sit inside and read or play games, I take care of the boat and a cruiser-racer is not the easiest boat to handle alone, or with a very short crew, in an oceanpassage. It is in that sense that I say that it is uncomfortable. About the water, my "family crew" wastes 300 liters of the stuff in around 4 days, so even being conservative and cutting that in half, I will need a lot more than the water carrying capacity of a J40, the same with the fuel, if I choose to use a watermaker. Sorry if I didn''t make myself clear. Paulo

I think that Paulo''s answer is really in line with the topic as we have been discussing it. Paulo sounds like he understands the needs of his family and given those needs the limited tankage, etc would be a problem. It is exactly to the point that boats like the J-40 are not made for everyone and that they may only make sense for people who are willing to live with some trade-offs for a additional performance. That said, I am not sure that I agree with all of Paulo''s comments. For example "I am talking about taking care alone of those big sails." Handling a boat like a J-40 should actually be easier than handling a heavier displacement boat. While the J-40 has a lot of sail area for its weight, it does not have a lot of sail area for a 40 footer. A typical, heavier displacement 40 footer would normally have an even larger sail plan than the J- and would not have the high quality sail handling hardware that is typically found on boats like the J-40. J-40''s actually are designed to be great short/single-handers. The same thing applies to heel angles. While a J-40 with its full racing sail plan is indeed biased towards lighter air performance and so has a lot more sail than would be ideal as windspeeds build, in the big picture the easier driven hull of the J-40 allows it to get by with a smaller sail plan relative to stability when in cruising mode. More specifically the comparatively small need for sail area to over come drag combined with the J-40''s comparatively higher vertical center of buoyancy relative to its comparatively low center of gravity means that the J-40 in cruising mode may actually heel less than a heavier displacement cruiser. Respectfully, Jeff

- ?

- 173.8K members

Top Contributors this Month

J/40 Detailed Review

If you are a boat enthusiast looking to get more information on specs, built, make, etc. of different boats, then here is a complete review of J/40. Built by J Boats and designed by Rod Johnstone, the boat was first built in 1984. It has a hull type of Fin w/spade rudder and LOA is 12.19. Its sail area/displacement ratio 17.89. Its auxiliary power tank, manufactured by Volvo, runs on Diesel.

J/40 has retained its value as a result of superior building, a solid reputation, and a devoted owner base. Read on to find out more about J/40 and decide if it is a fit for your boating needs.

Boat Information

Boat specifications, sail boat calculation, rig and sail specs, auxillary power tank, accomodations, contributions, who designed the j/40.

J/40 was designed by Rod Johnstone.

Who builds J/40?

J/40 is built by J Boats.

When was J/40 first built?

J/40 was first built in 1984.

How long is J/40?

J/40 is 10.36 m in length.

What is mast height on J/40?

J/40 has a mast height of 13.47 m.

Member Boats at HarborMoor

Attainable Adventure Cruising

The Offshore Voyaging Reference Site

- Q&A—Sailboat Performance, When The Numbers Fail

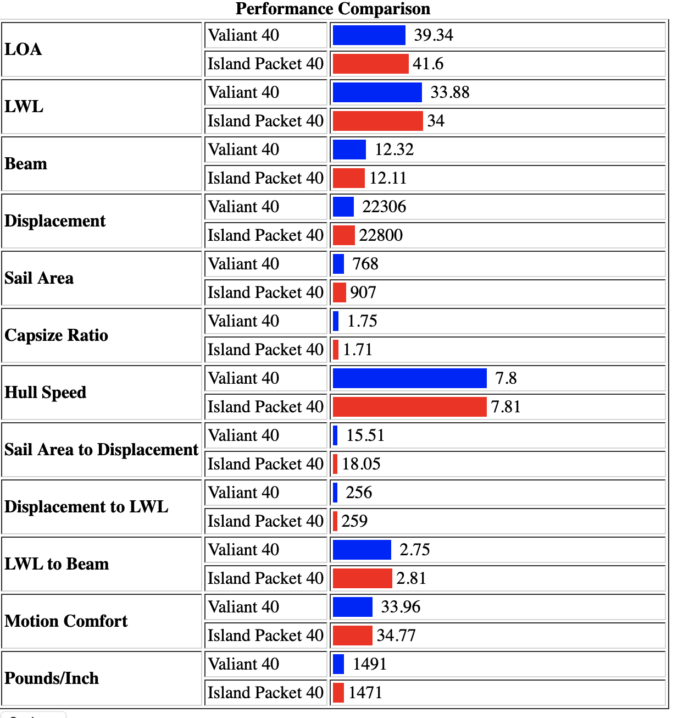

I’ve compared a Valiant 40 to an Island Packet 40 using Tom Dove’s Sail Calculator and it appears to me that the IP 40 beats the Valiant in almost all categories. And yet the IP is slower based on its PHRF rating. And of course the IPs also have a reputation for being slow. Wonder what’s going on here? Does the additional wetted area of the IP’s keel make the difference?

Login to continue reading (scroll down)

Please Share a Link:

Boat Design/Selection Child Topics:

- "Morgan's Cloud"—J/109 Fibreglass Fractional Sloop

- "Morgan's Cloud"—McCurdy and Rhodes 56-foot Aluminum Cutter

- Adventure 40

- Colin on Good Design

- Offshore Motor Boats

- Online Book: How To Buy a Cruising Boat

- Outbound 46

More Articles From Boat Design/Selection:

- Colin & Louise are Buying a New Sailboat

- Talking About Buying Fibreglass Boats With Andy Schell

- US Sailboat Show Report—Boats

- Some Thoughts On Smaller Older Cruising Boats

- Wow, Buying an Offshore Sailboat is Really Hard

- Hull Design Torture Test

- Of Dishwashers and Yacht Designers

- Which Is The Best Boat For Offshore Cruising?

- Meeting Up With Steve and Linda Dashew

- Cruising On Less Than $15,000/Year, Including The Boat—What It Takes

- How Not To Buy a Cruising Boat

- Where Do We Go From Here?

- The Boat Design Spiral

- Spade Rudders—Ready for Sea?

- Trade Offs in Yacht Design

- We Live in Rapidly Changing Times

- Long Thin Boats Are Cool

- Beauty and The Beast

- Q&A: What About Ferro-Cement Boats?

- Thinking About a Steel Boat?

- Your Boat Should Forgive You

- New Versus Old

- Rudder Options, Staying In Control

- “Vagabond”—An Extraordinary Polar Yacht

- Learning The Hard Way

- The Real Story On The MacGregor 65

- An Engineless Junk Rigged Dory—Another Way To Get Out There

- S/V “Polaris”, Built For The Arctic

- Boats We Like: The Saga 43

- Designers of “Morgan’s Cloud” Have A New Website

- Q&A: Interior Layout And Boat Selection

- A Rugged Boat For The High Latitudes

- Q&A: Homebuilding A Boat

- Q&A: Sailboat Stability Contradiction

- Are Spade Rudders Suitable For Ocean Crossings?

- There’s No Excuse For Pounding

- Q&A: Tips On Buying A Used Boat For The High Latitudes

- Used Boat For Trans-Atlantic On A Budget

- QA&: Is A Macgregor 26M Suitable For A Trans-Atlantic?

- Q&A: Used Colin Archer Design Sailboat

We cruised alongside an IP40 for several months in the Caribbean. We were in our Morgan 382. We generally outperformed the IP everyday, but… going to weather? They might as well have not even tried – we skunked ’em every time. I understand that this doesn’t really have a whole lot to do with this article, but it’s a fun memory nonetheless. 🙂

Sure, that makes sense.

Hi John and all, A very interesting comparison. I have always thought Valliants sailed “above their numbers” and that Bob Perry had nailed some sweet spots. But I am clearly not an uninterested party. Since there is a frequent confusion that often comes my way, I will clarify that a Valiant 42 (which I have sailed for 20+ years), while having the same (or very similar hull) as the Valiant 40, has a taller rig with more sail area, an upgraded underbody with a newly designed keel, and a 2-foot anchor handling platform (hence the “42”) allowing the jib to be farther forward. These were among numerous cosmetic changes. Both are great boats that have many miles under their keel. (And may hold the record for circum-navigations among production [semi-custom] boats). My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Yes, that was my point about being careful of variants when comparing boats.

I’d like to make a couple of points that will clear up this “mystery“.

1. Carl’s Sail Calculator, hosted at the Tom Dove website is a wonderful tool, BUT It’s subject to the same problem any calculation tool is vulnerable to: Garbage In = Garbage Out. In this case the source of garbage is that users supply the data on various boats. I have submitted quite a few myself, mainly because I was unable to find an existing entry with anything like correct numbers. I can remember looking at three different entries for the same production sailboat, with numbers that were all over the place. Some are so far off that you couldn’t even blame fat finger data entry, somebody just had to make some numbers up! You simply cannot rely on the data for any given boat without vetting it thoroughly yourself. There are lots of sources for doing that: Sailboat Data, scans of owners manuals and, sometimes, a factory website… Which brings us to my second point: the curious case of Island Packet.

2. Both the Valiant 40 and the IP 40 are cutters, and have similar sail areas. Wait, what did he say??? The graphs above show the IP 40 with a much greater sail area and a much better SA/D ratio! Yes, they do. And the numbers for the IP 40, seem to be drawn directly from information provided by Island Packet. But there’s one very big problem. The conventional, accepted way to measure sail area is to measure 100% of the fore trangle,. Stay sails on cutters are NOT counted. This makes a huge difference when comparing a boat designed by Bob Perry, who is very scrupulous about using accepted values, and a company that, let’s say, likes to provide numbers that present their products in the most favorable light. Plug in the accepted measurements for the IP 40 and you get a SA of 774 sq. ft., just about the same as the numbers given for the Valiant 40. This results in a ripple effect of other values and, when coupled with the reasons given above as to why the Valiant 40 should be faster, you quickly see why the V40 will be faster on almost every point of sail. QED

Hi Gregory,

Yes, very good points. (I delve into cutter sail area here: https://www.morganscloud.com/2015/09/17/12-reasons-the-cutter-is-a-great-offshore-voyaging-rig/ )

That said, the point I was making is not just one of data entry failure, but also to point out that even if the data entry were perfect a boat with the same numbers could be far faster because of other factors like a fin keel.

I guess this comes from Sailing Atticus given their recent videos. I’ve had a quick look for our Rival 38 to see how it might compare (with a reputation for being slow in light airs). PHRF 141 which is right in the range of values for a Valient 40.

Sadly the RYA system called NHC which replaced the Portsmouth Yardstick for cruisers doesn’t have the IP or Valient in its base list (which is now 6 years old so not sure if it is being maintained) https://www.rya.org.uk/racing/Pages/nhc.aspx

I guess there might be some with an IRC rating but from here http://www.phrfne.org/page/handicapping/asdg it looks like we can’t get a comparison without knowing the name of an IP40 or Rival with a rating.

Plus ours is the ketch version of the R38 (possibly the only one still rigged as a ketch) so everything is going to be different.

Thanks for the explanation.

Another thing I was thinking about for the older boats is that there will be a very variable take up of different technologies, particularly in terms of sails. So how many boats have retrofitted in-mast furling without battens? How many have invested in asymmetric downwind sails, in code zero upwind? I would imagine that there will be a much wider spread among these older classes now then there would have been when they were built.

I used to race my Cal 35-2 (modified fin 5’) and in my fleet there were 3 J 30’s. They always, always ate my lunch. HOWEVER, the last time I raced with them the wind was blowing 15-20 minimum. We were going upwind against some current/tide and 2-2.5’ waves. I did not reef and they could not stay with me. If you could’ve seen the look of WTF? in their faces, it was, to me, a very satisfying afternoon. I built up a large enough lead that they couldn’t catch me downwind ( broad reach, where my boat excels) and I took 1st place….I stopped competitive racing on my boat that afternoon, on top. Yea haaaaa.

Sailing a stumpy-masted, cutter-rigged steel motorsailer, I can relate. I was able to get 3.3 knots SOG in 8 knots of apparent wind sailing through a race course off Toronto on the most favourable point of sail for me, and the gap in the fleet was enough to make it through without affecting the race. I got unusual pleasure from seeing the racers looking at the boat, and then looking at the stern for the telltale sign of prop wash, and then looking at the boat’s serene progress. The point is that any boat can sail up to, and occasionally beyond, its “numbers” if the situation and the skill set permit, which is why I don’t think they should ever be taken as gospel, merely a set of probabilities. There’s too many club fleets dominated by old boats driven by canny skippers and a generous rating to really argue otherwise.

My understanding of PHRF ratings is they are based on past racing performance rather than design…… if you do well racing, your handicap changes so you do less well.

How this applies to a series of production boats as compared to one-off’s maybe reflects what type of sailor as well as the racing ability of the sailors that buy them.

Hi Dennis, That’s a common perception. But, as a past PHRF handicapper, I can tell you that is not the intent of PHRF, or in most cases the practice. The core premise of PHRF is that only the boat is handicapped, not the crew, and that is done assuming that said boat has good sails, a clean and faired bottom, properly tuned, and in all ways optimized within the rules to race.

In practice, classes that have a lot boats in PHRF spread over several fleets are very fairly handicapped and the best sailors win consistently, just as they would in a one design fleet. With rare boats and custom boats it’s more difficult, but overall PHRF is surprisingly good at taking the crew effect out of the final number.

Hi John, In 2002 I had the hull of my steel 45 ft motorsailor Delta Wing , faired, and I modified the rudder for slightly increased area. My next race was the 400 mile Lord Howe Island race which I won on performance handicap. As a result my handicap was increased. The next race 2 months later was the Sydney Hobart and we enjoyed a following wind for the entire race varying from 20 to 43 knots. Despite blowing out our only spinnaker and resorting to the much smaller MPS for the last 200 miles, we also won that race on performance handicap. Our handicap was really upped then.

Hi William,

Getting your handicap raised is always disheartening, but that does not mean that the handicappers were handicapping your sailing skills rather than the boat. I’m guessing that your boat is custom, which is always the hardest for PHRF to handle fairly. That said I would suspect the handicap committee looked at a heavy motor sailor that came out and won two important races back to back and concluded she was faster than they initially thought she was, regardless of crew skills. The fact that you won the S-H after blowing out your big spinnaker would have been a factor too, if the committee knew, and I bet they did.

If I were doing this comparison where the usual suspect parameters and ratios s tell a counter-intuitive story, I’d be inclined to also look at the hull lines and other particulars like prismatic coef. and wetted surface. I would venture a guess that the IP is considerably higher on both accounts. I also think published displacement numbers are merely suggestions. With boats like these that have 1500lb per inch immersion (which suggests waterplane areas are about equal), you are looking at a very considerable increase in displacement sitting only a few inches down, which is usually not perceivable to the untrained eye. Lastly, those IPs tend to use in-mast furling which produces a terrible mainsail shape. Just as good sails are unrated speed, bad sails are unrated drag.

40' 1989 J Boats J40

Accepting cash offers until the end of the month. Welcome to show it anytime. Boat is in rough shape and needs alot of tlc but the bones are a Jay.

Specifications

Basic information, dimensions & weight, tank capacities, accommodations, vessel details.

Share This Yacht

Presented By: Reggie Mason 813.477.2102 813.773.6595

Contact A Yacht Specialist Fill out the form below and one of our yachting specialists will get in touch with you.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Find detailed information about the J/40 sailboat, including hull type, rigging type, dimensions, displacement, ballast, sail area, and more. See also sailboat calculations, rig and sail particulars, and sailboat forum topics.

The ballast displacement ratio indicates how much of the weight of a boat is placed for maximum stability against capsizing and is an indicator of stiffness and resistance to capsize. Formula. 36.11. <40: less stiff, less powerful. >40: stiffer, more powerful.

The J40 accommodation layout. The J40 is a sloop-rigged boat with a fin keel and a spade rudder. The sail area is 765 square feet, which gives it a sail area to displacement ratio of 18. The boat is powered by a 43 hp diesel engine. The J40 has a sleek and elegant hull shape that is optimized for speed and stability.

1 Sailboats / Per Page: 25 / Page: 1. 0 CLICK to COMPARE . MODEL LOA FIRST BUILT FAVORITE COMPARE; J/40: 40.00 ft / 12.19 m: 1984: ShipCanvas. KiwiGrip. Bruntons ... We use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. We do this to improve browsing experience and to show (non-) personalized ads. ...

The J40 is a 40.0ft masthead sloop designed by Johnstone and built in fiberglass by J Boats between 1984 and 1993. 85 units have been built. The J40 is a moderate weight sailboat which is a reasonably good performer. It is stable / stiff and has a good righting capability if capsized. It is best suited as a coastal cruiser.

Today, well-equipped J/40s can be bought for under $130,000, which is a lot for a used 40-foot boat, but close to $100,000 less than the new J/42 that has been designed to replace it. Compared to other boats in this size and price range (the Tartan 40, Nordic 40, Bermuda 40 and Bristol 41) the J40 is notable for its simplicity, speed and ease ...

18. 18. Dspl/L. 204. 204. J/40 Offshore Cruising Sailboat Technical specifications & dimensions- including layouts, sailplan and hull profile.

The J/40 was the first bluewater offshore cruising boat built by J/Boats. Many J/40s are still sailing actively today with a very supportive and helpful J/40 Owner's Association. Since the mid-1980's the J/40 has enjoyed success racing under the ORR and PHRF handicap system, particularly in offshore events.

The J/40 was offered with a shoal draft keel drawing 5' and a deep draft keel drawing 6' 5". The rig is a low aspect sloop with 773 square feet of sail area. The larger mainsail and smaller headsails are more easily managed by a short-handed crew. The rudder is a large, partially balanced spade that provides excellent steering control.

Complete Sail Plan Data for the J/40 Sail Data. Sailrite offers free rig and sail dimensions with featured products and canvas kits that fit the boat.

The J/40 was my favorite boat for 1985. It might be fun to compare the J/40 with my design, the Valiant 40. Both boats show similar dimensions with identical waterlines and I dimensions. The major difference is that the J/40 weighs 15,500 pounds and the Valiant weighs 23,000 pounds. This works out to a D/L ratio of 176 for the J/40 and 261 for ...