- Boats for Sale

- Baltic Yachts

New and used Baltic Yachts for sale

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Netherlands

- Sint Maarten (Dutch Part)

- Baltic Yachts 37

- Baltic Yachts 43

- Baltic Yachts 46

- Baltic Yachts 51

- Baltic Yachts 55

- Baltic Yachts 62

- Baltic Yachts 66

- Baltic Yachts 78

Find your dream Baltic Yachts on TheYachtMarket today. We have Baltic Yachts brokers and sellers from around the world at great prices.

History of Baltic Yachts

Baltic Yachts is a world-leading yacht builder that's built on a strong heritage of design and engineering excellence. The company was founded in 1973 by a team of experienced yachtsmen and craftsmen who sought to create a range of high-performance, custom-made yachts that blended innovative technology with traditional craftsmanship. Since its inception, the Finland-based company has consistently pushed the boundaries of yacht design and construction, establishing itself as a market leader in the luxury yacht sector.

The boat manufacturer started operations in the village of Bosund on the west coast of Finland. The early years were focused on catering to the local market, but Baltic Yachts quickly gained international recognition, with its sailboats being praised for their advanced design, excellent performance, and superior build quality. Significant milestones in the company's history include launching the cutting-edge Baltic 141 Canova in 2019, which showcased the manufacturer's technological prowess with its innovative DSS foil system.

Today, Baltic Yachts continues its tradition of excellence at its state-of-the-art shipyard in Jakobstad, Finland. The shipyard is renowned for its advanced facilities and skilled workforce, excelling in carbon fibre technology to deliver some of the world's most advanced yachts. Despite progressing towards larger and more complex yachts, the company remains true to its core values, delivering boats of exceptional quality and performance that exemplify the best of Scandinavian design and craftsmanship.

Which models do Baltic Yachts produce?

Baltic Yachts produce a range of boats including the Baltic Yachts 51 , Baltic Yachts 66 , Baltic Yachts 62 , Baltic Yachts 37 and Baltic Yachts 46 . For the full list of Baltic Yachts models currently listed on TheYachtMarket.com, see the model list in the search options on this page.

What types of boats do Baltic Yachts build?

Baltic Yachts manufactures a range of different types of boats. The ones listed on TheYachtMarket include Sloop , Cruiser , Offshore cruiser , Cruiser/racer and Bluewater cruiser .

How much does a boat from Baltic Yachts cost?

Used boats from Baltic Yachts on TheYachtMarket.com range in price from £36,200 GBP to £2,150,000 GBP with an average price of £500,000 GBP . A wide range of factors can affect the price of used boats from Baltic Yachts, for example the model, age and condition.

Sign up to our newsletter

By submitting this form, you agree to our Privacy & Cookie Policy

Change units of measure

This feature requires cookies to be enabled on your browser.

Show price in:

Show lengths, beam and draft in:

Show displacement or weight in:

Show capacity or volume in:

Show speed in:

Show distance in:

- Frank Magazine

- Denison History

- Virtual Tours

- Alaskan Yachts

- Azimut Yachts

- Back Cove Yachts

- Beneteau Yachts

- Benetti Superyachts

- Bertram Yachts

- Boston Whaler

- Broward Yachts

- Buddy Davis Sportfish

- Burger Yachts

- Cabo Yachts

- Carver Motoryachts

- Center Console

- Chris-Craft Yachts

- Cruisers Yachts

- DeFever Trawlers

- Dufour Sailboats

- Fairline Yachts

- Feadship Yachts

- Ferretti Yachts

- Formula Yachts

- Fountaine Pajot Cats

- Grady-White

- Grand Banks Trawlers

- Hargrave Yachts

- Hatteras Yachts

- Hinckley Picnic Boats

- Horizon Yachts

- Hydra-Sports

- Intrepid Boats

- Jarrett Bay Sportfish

- Jeanneau Yachts

- Kadey-Krogen Trawlers

- Lazzara Yachts

- Luhrs Sportfish

- Marlow Yachts

- Maritimo Yachts

- Marquis Yachts

- McKinna Motoryachts

- Meridian Yachts

- Midnight Express

- Mochi Craft

- Neptunus Motoryachts

- Nordhavn Trawlers

- Nordic Tugs

- Ocean Alexander Yachts

- Offshore Yachts

- Oyster Sailing Yachts

- Pacific Mariner Yachts

- Palmer Johnson Yachts

- Pershing Yachts

- Prestige Yachts

- Princess Yachts

- Pursuit Yachts

- Riva Yachts

- Riviera Yachts

- Sabre Downeast

- San Lorenzo Yachts

- Sea Ray Boats

- SeaVee Central Consoles

- Selene Trawlers

- Scout Yachts

- Sunseeker Yachts

- Tiara Yachts

- Trinity Superyachts

- Viking Yachts

- Westport Yachts

Baltic Yachts

Baltic Yachts has been building high-tech, semi-custom sailing yachts, and custom superyachts since the early 1970s. While working for Finnish shipyard Nautor, five young builders decided to split from the firm and create their own legacy. Baltic Yachts was created to fill the niche of high-quality sailing yachts for racing applications. Baltic Yachts would continue to innovate with lightweight materials such as carbon fiber and new building techniques to reduce weight.

2 years later in 1975, Baltic Yachts would be acquired by Finnish shipbuilder Hollming Ltd., enabling expansion of its marketing efforts.

- Year Established 1973

- Shipyard Location Finnland

- Boat Construction

- Boat Category Luxury Yacht, Superyachts , Megayachts

Baltic Yachts For Sale

85' baltic 2018, barcelona, es-b, spain, 49' baltic 2002, fort lauderdale, fl.

- View All Baltics For Sale

Baltic Yachts by Vintage

- Baltic Yachts Older - 2004

- Baltic Yachts 2005 - 2008

- Baltic Yachts 2009 - 2013

- Baltic Yachts 2014 - 2017

- Baltic Yachts 2018 +

Baltic Yachts by Location

- Baltic Yachts in Florida

- Baltic Yachts in Michigan

- Baltic Yachts in Washington

- Baltic Yachts in New York

- Baltic Yachts in California

- Baltic Yachts in Massachusetts

Yachts Recently Added

- Within 1 Days

- Within 3 Days

- Within 7 Days

- Within 14 Days

- Within 30 Days

- Within 60 Days

Baltic Yachts by Size

- Baltic Yachts 65' - 80'

- Baltic Yachts 81' - 95'

- Baltic Yachts 96' - 115'

- Baltic Yachts 116' - 130'

- Baltic Yachts 131' - 150'

- Baltic Yachts 151' +

Baltic Yachts by Price

- Baltic Yachts Under $500,000

- Baltic Yachts $500,000 - $750,000

- Baltic Yachts $750,000 - $1,000,000

- Baltic Yachts $1,000,000 - $5,000,000

- Baltic Yachts $5,000,000 - $10,000,000

- Baltic Yachts $10,000,000 +

Speak to a Baltic Yacht Specialist

Fill the form below and let's talk about the right boat for you., market updates, be in the know.

Sign me up to receive market updates. . I'm interested in:-->

- Price Changes

- New to Market

- Current list of 's for sale

- An alert when 's are added to the MLS

Yachts for Sale

Selling a Yacht

Tenders & Toys

Recent Sales

NEVER SAY NEVER AGAIN

Yachts for Charter

Destinations

Experiences

Charter Management

Charter Guide

Yacht Marketing

How to Charter

Superyacht Management

Crew Structure

Crew Management

THE WELLESLEY

Superyacht Construction

New Yachts for Sale

Yacht Design

Yacht Shipyards

Custom Construction

Built on Trust

Heesen 55m Steel

Benetti Oasis

Yacht Shows

News & Blog

Baltic Yachts for Sale

Baltic yachts for sale.

Baltic Yachts are some of the finest built-in Finland. The yard started building yachts in the 80s and accumulated experience on the 20+ superyachts they delivered over the years. The yard has been delivering yachts of the utmost quality up to 66m and 340GT.

Whether you are taking the very first step towards Superyacht ownership or already have a fleet, a Baltic Yacht is a strong buy.

USED Baltic YACHTS FOR SALE

If there are no brokerage yachts available on the market, you can get in touch with our brokers to find an off market one or build a new one.

YACHTS FOR SALE

YACHTS FOR CHARTER

CHARTER MANAGEMENT

+377 97 77 67 57

Privacy Policy

SEO by The Agency

REQUEST OFF MARKET YACHTS

Leave us your contact detail and our team will be in touch shortly to provide you with your quick request.

Yachts for sale

Selling a yacht

Recent Sale

BROKERAGE INSIGHT

Sailing yachts.

Register your interest in purchasing a sailing yacht and get our latest insights on the most exclusive yachts for sale, price reductions and special conditions on yacht sales.

Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Baltic 67 review: Finnish superyacht yard goes back to its roots with no-compromise cruiser

- Toby Hodges

- March 28, 2019

When a renowned superyacht yard builds a 67-footer for short-handed cruising you can be sure the result will be something special

Were money no object and you wanted the ultimate yacht for long-term cruising, what would you choose? How large could you go without needing a paid crew? What do you really need length and space for and how important is displacement and potential speed to you?

These were the sort of questions crowding into my head on first viewing the sensational new Baltic 67 at the Cannes Yachting Festival . It is truly striking. The quality of the yacht is undeniably world class, but it’s the precision of design and engineering that soon absorbs you.

The owner of this first boat is a highly experienced cruising sailor, boat owner and navigator, so joining him for a 24-hour trial from Mallorca proved the ideal way to get under the gleaming composite skin of this athletic new model.

The concept is about combining the pleasure of pure sailing with ease of handling for long-distance cruising at high average speeds. It is the alternative to a full custom yacht – all the engineering is already calculated – but a great deal of flexibility has been worked into the design, with options including single or twin rudders, a fixed or telescopic keel, multiple cabin layouts, and a carbon or epoxy sandwich hull.

Wanting to return to its mid-size fast cruiser roots, Baltic Yachts teamed up with designers and fellow in-demand superyacht specialists Judel Vrolijk and Design Unlimited. The result is this exceedingly attractive, modern-looking sloop, with a powerful hull shape, a flush foredeck and a low-profile coachroof.

Powered sail handling systems means Manyeleti can be sailed by just two

The Baltic 67 is very much at the luxury and custom end of the production yacht scale, so our light wind trial of the boat focused more on the various choices and details aboard and how they might be relevant to sailors in general. Hull number one in particular had a lot of owner input.

Manyeleti , the first 67, belongs to Erik Lindgren. It is his fifth yacht from Baltic after a string of upgrades that started with a used 39 in 1989. “It’s very different to design and build your own boat – in my case using nearly 30 years of offshore sailing experience,” Lindgren explains.

Swede Lindgren travelled to the yard once a month and was in daily contact with the project manager, Kjell Vesto.

The Lindgrens’ plan is to head off on another world cruise in a couple of years time, when Erik’s teenage children have finished school. His shakedown sail involved a 5,000-mile trip from Finland to and around the Mediterranean.

“Not a single thing broke,” he reports, saluting Baltic’s build quality. “I could literally go to El Corte Inglés, stock up, fuel up and sail across the Atlantic.”

CNB 76 boat test – more boat for your money

It may sound daunting, but it seems 60ft is no longer a big boat. In typical Philippe Briand fashion the…

Walk the course with Mike Broughton- navigator onboard the brand new Baltic 115 Nikata

Start date: Monday 22nd February 2016 Course: Approx. 600nm non-stop around 11 Caribbean Islands Organised by: The Royal Ocean Racing…

The Baltic 67 is as big as you can go without needing a pro crew, argues Erik Lindgren. “I’ve spent a lot of time on World ARC boats… it’s the details that make living on board easier. This is a technical boat, but is less dependent on systems than our old Baltic 56. On the other hand it’s great to have aircon and a lifting keel.

“Half the time spent aboard will be for long distance stuff and holidays for the two of us, but a lot of the time will be spent with friends and family too.”

Privacy at this size is a big benefit. “I have no need to have a big boat for show,” says Lindgren, “but I wanted to have the things I need.”

The retractable arm for the anchor roller is an engineering masterpiece. It rises from the anchor locker at the touch of a button

The most important features he wanted, which help explain the jump in size from his previous 56, were a furling boom, a large, practical galley, four cabins and a tender garage large enough to house a forward-facing dinghy. While his yachts have grown and become more complex, Lindgren maintains that the methodical way Baltic builds boats results in a lot fewer problems.

A carbon furling boom is an eye-watering investment, but it does make the hoisting, reefing and lowering of sails a quick and largely hassle-free procedure. It can make the difference to whether you go sailing or not. Within minutes of leaving Palma’s breakwaters, we had main and jib unfurled and were matching the 8 knot wind speeds.

Manyeleti is hull number one in the Baltic 67 series

Easy performance

The Hall carbon boom uses an electric mandrel motor that is synchronised with the halyard to avoid too much sail spilling out during a hoist. The traveller is also electric, while the sheet car pullers, backstay, vang and furlers are hydraulically-operated. The result is the ease of push-button sailing typically used on modern performance superyachts.

We spent the first few hours reaching across Palma Bay. Despite having 24 hours aboard, the most breeze we found was 11 knots, which translated to 9.5 knots boatspeed – very respectable under white sails only (fully battened main and non-overlapping jib). The majority of the time was spent close-hauled, matching the single-figure wind, even exceeding it when it dropped below 6 knots.

Neat details: the forward end of the jib car puller, which is hydraulically powered

I found myself gravitating to the side deck to sit and steer, instinctively wanting to sail the Baltic 67 like a cruiser-racer. There are good views over the low coachroof and flush foredeck, but nothing except freeboard height to prevent a wet backside if the decks ship green water.

The helmsman can also sit forward of the wheel and reach the two winches. I like the way the primary is mounted inboard, though the positioning of the turning block for the jib sheet creates an obstacle on the side deck. Baltic reasons that it helps provide the option to use either winch for the sheet.

Speed for oceans

A flying sail would have helped to get the most out of the conditions, but Lindgren was still awaiting delivery of a Code 0 and A3, both on top-down furlers. However, even when the evening breeze died to around 4-5 knots, the Baltic 67 still provided an enjoyable experience on the helm. It’s rare that you can say such a thing while only using main and jib.

The 67 is designed for potent offwind performance, to limit engine use on transocean voyages. The aggressive sail area to displacement ratio of 30.9 is possibly taking things too far: the boat has so much power to weight that it will need to be treated as a real performance cruiser and tamed accordingly (i.e. reefed early). But what our trial sail did show was how well the Baltic 67 fulfils its brief of being able to offer enjoyable sailing in light wind.

“Bluewater boats don’t usually sail in 10-15 knots downwind – and we had a lot of that,” Lindgren points out, with reference to their previous Pacific crossing. “At 150º true, this boat is sailing at 8-9 knots, which is a big difference. As long as you are over 8 knots you are properly moving through the water,” he reasons. “Below that you’re in the swell and not in control.”

The twin pedestals are well designed to site plotter screens and remote controls for powered deck functions and sail handling

With the relatively low coachroof and cockpit backrests and aft positioning of the helms, protection from the elements may be a concern. When you look at Baltic’s large new designs in build, the 142 and 146, both have lengthy deckhouses that provide plenty of protection. But it chose the more in-vogue deck design for this semi-custom size, so its solutions for cockpit protection depend largely on a retractable sprayhood and bimini. These can remain in place while sailing and have already been tested in up to 40 knots.

The cockpit area on this first Baltic 67 has been adapted according to the owners’ wishes, including a narrower space between benches and no fixed table. The Lindgrens like to be able to brace feet between benches and to be able to sleep on the sole between them when offshore. The table and carbon legs stow beneath the central saloon soleboards.

We anchored at dusk at Es Trenc beach, 25 miles to the south-east of Palma, in water so clear we could pick the spot to drop the hook between weed patches. The ability to anchor in less than 4m amply demonstrated the appeal of a lifting keel. The keel system, from the highly reputable Italian brand APM, raises the T-keel hydraulically up to 2.5m.

The anchor arrangement is another fine piece of engineering: the arm is concealed in a shallow locker and rotates over and into place at the push of a button. The roller then extends out to keep it clear of the stem. The second Baltic 67 will have a fixed roller incorporated into the bowsprit.

The furling jib and powered padeye are recessed neatly

Open transom choice

The garage houses a 3.2m dinghy stowed longitudinally, with the engine mounted, between the dual rudders. Lindgren chose an AB tender with aluminium hull (53kg). It has a 20hp outboard so can plane with four adults yet is light enough to be dragged up the beach. He also opted for an open transom that, although an unconventional choice for ocean cruising, gives easy access to the swim platform and dinghy.

There is copious stowage space throughout the Baltic 67. In addition to the tall sail locker in the forepeak, the aft quarter lockers easily swallow electric bikes, inflatable paddleboards, snorkel gear, waterskis, spare fuel and a liferaft valise. Here there’s also access to the steering gear with independent autopilots used on both quadrants.

I particularly like the way multiple Antal T-lock fittings are flush-mounted along the toerail and in the cockpit. These enable quick and easy swivelling toggles to be inserted for loops and blocks, or for harness attachments.

Weight versus noise

The following morning was windless, leaving us with a three-hour motor back to Palma. The 150hp six-cylinder Steyr was specified for its low noise and emissions, and drives a four-blade Bruntons prop via a standard shaft.

E-glass was chosen over the standard carbon hull. Lindgren’s previous Baltic 56 was carbon and he wanted the better noise insulation over the weight difference (up to one tonne). The 67 is a very quiet, relaxing boat under motor, with no need to raise voices under power.

The spacious saloon has enough room for both dining and coffee tables

Down below the Baltic is an aircon-cooled haven of charm and exquisite quality. The more time I spent aboard and the more I learned of the systems and engineering, the more I began to appreciate what sets this boat apart.

The Design Unlimited styling is elegant and tasteful, with a mahogany finish on this first boat. With four different layout configurations plenty of scope is allowed for owner customisation. But behind the scenes is what you really pay for with the Baltic. It’s the telling result of what happens when a yard goes down in model size – this 67 is built like a superyacht.

For example, the engine room, used for hot items like engine, genset and water-heater, links through to a proper mechanical/utility room abaft the galley, where equipment is mounted on three walls for easy access (including chargers, inverters, pumps, watermaker and compressors).

“The thinking is that everything should be in reach and that you should be able to maintain it easily,” says Lindgren, pointing to the Spectra watermaker (his fourth) mounted on one bulkhead.

The boat’s systems are beautifully laid out for ease of inspection and maintenance

Stowage throughout has been brilliantly conceived. The 2,000lt of water and diesel tanks, plus the batteries, are all mounted centrally, under the saloon, leaving cavernous practical stowage under the berths. Custom-made fabric bags are used under the saloon seats to maximise useable volume.

Lifting the carbon sandwich soleboards at the base of the companionway reveals the sea chests and main manifolds for fuel and water, a prime example of the meticulous and practical systems layout. The 1,440Ah of lithium gel batteries further forward have a reservoir surrounding them, which can cool the cells if necessary without flooding them. And there are custom-made drip trays below any filters to prevent mess or corrosion.

The keel uses a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) to activate the hydraulics, the cylinders for which can be replaced from within the boat. All other electrics are on manual relays. The fuse locker is a work of art and opens out for full access to the wiring, with every wire and fuse numbered and labelled.

Smart cabin choice

Manyeleti ’s owner’s cabin, with adjoining heads and shower in the forwardmost section, has an offset double berth positioned aft by the main bulkhead, a relatively central area of the boat to sleep. However, on passage, Lindgren says he sleeps on deck, or in the single cabin amidships. There are also leecloths on the saloon berths, a comfortable option if guests don’t want to share the twins.

The owner’s cabin is (purposefully) the only one aboard Manyeleti to feature a double bed

There is a good reason why there is only one double bed. Lindgren often sails with male friends, hence twin and single berths are a pragmatic choice. The use of a split heads and shower shared between the twin and single cabins is also sensible.

The central section of the interior is superb, with a traditional lower saloon, a navstation beside the companionway and a formidable U-shaped galley. It was important to the Lindgrens that the galley was large enough for two to work in yet still be seamanlike. The result is a very practical area with superb chilled, dried goods and crockery stowage. Ventilation ducts keep it nice and cool, though personally I’d want to have a hatch through to the cockpit.

Lindgren swears by the dishwasher, reasoning that it uses less water than washing up and helps keep the galley tidy. This and an induction cooker would be sensible options if you had sufficient power, and would avoid the need for gas.

The exemplary finish and smaller details help furnish the boat with a top quality feel. From the hinges, light switches and showerheads to the gas sprung hatches and overall joiner work, the Baltic 67 oozes quality.

The Baltic 67 has been designed with short-handed sailing in mind

Baltic 67: the verdict

Baltic has spent the last decade building some of the finest performance superyachts. You don’t receive commissions for yachts such as Hetairos , Pink Gin VI , or My Song without a top reputation, and to get that sort of quality on a 67-footer is truly special. Attention to detail and class of engineering and finish are hallmarks of this new model.

The Baltic 67 has the performance in light airs to match her on-trend looks and is a joy to helm. The choice of a comparatively unprotected cockpit and an open transom may not sit well with conventional bluewater sailors, but times are changing and this design is aimed as much at port-hopping from Portofino as at Pacific passagemaking . It is the solutions, stowage and systems employed throughout that help make it a valid option for distance cruising.

The Baltic 67 has the legs to outrun virtually any other cruising monohull and to keep sailing fast in light apparent winds. To know you’re buying the best in terms of design and composite build – and created by the same team involved in a yacht that costs tens of millions – must help compensate for the significant initial outlay. For the rest of us, we can but dream.

Specification

LOA: 20.52m (67ft 4in)

LWL: 19.20m (62ft 12in)

Beam (max): 5.45m (17ft 11in)

Draught (max): 3.90m (12ft 10in)

Draught (telescopic): 2.50m (8ft 2in)

Displacement (lightship): 24,400kg (53,792lb)

Ballast: 9,000kg (19,841lb)

Sail Area: 255.6m2 (2,751ft2)

Berths: 7-8

Engine: 150hp

Water: 1,000lt (220gal)

Fuel: 900lt (198gal)

Sail Area/disp ratio: 30.9

Disp/LWL ratio: 96

Price: €3.95 million (ex. VAT)

Design: Judel/Vrolijk & Co and Design Unlimited

Half a century at the cutting edge

Fifty years ago in Finland five young men shared a controversial idea and an ambitious plan. They quit their jobs at Nautor and set out to create a new style of offshore cruiser racer – lighter, stiffer and faster than almost anything else on the market.

‘We just got together one day and the idea came up,’ says Per-Göran “PG” Johansson, one of the five founding fathers of Baltic Yachts back then and still one of its directors today. ‘We were not alone thinking “light is better” but most boatyards and naval architects favoured heavier designs. Some of our competitors published studies for marketing purposes arguing that heavy was better. One of their claims was “heavy does not stop in waves due to the inertia of the mass”. Another was “the client gets more kilos for his money”. We remained convinced and carried on with our lightweight, hi-tech way.’

History soon proved Johansson and his colleagues to be absolutely correct and the company they founded became a world leader in the production of large, high-performance sailing yachts.

Before any of it could happen, first they had to clear a patch of pine forest at Bosund near Jakobstad and build a shed in which to do it.

Still in use as a joinery workshop, that first shed is finally about to be decommissioned along with the whole facility that grew up around it. This year, Baltic Yachts is moving all operations to Jakobstad where a new state-of-the-art building will more than double the size of its existing waterfront location.

There’s a world of difference between the series-produced Baltics of the 1970s and the full-custom superyachts that have become the yard’s primary focus alongside its ongoing small-series, semi-custom production.

However, from the first Baltic 46 Diva (now Queen Anne) all the way to its current projects via some of the most advanced sailing yachts in each of the last three decades, the core DNA is arguably unchanged.

‘Baltic Yachts is still very much true to its original values,’ Johansson says. ‘We started as a series production yard but with more flexibility built in than most competitors, using hi-tech methods to achieve better sailing performance and handling characteristics. With time we moved over more and more to full custom projects, which required changes in our approach.

‘The projects became more individual in concept, in styling and in materials and methods used.

In that process you lose some of the things that originally earned your company its reputation. However, even our cruising projects have been very hi-tech and in that sense they’ve followed our original philosophy, “lighter is faster and better”. Some of the high-performance projects challenged us to take technology much further, increasing our know-how and potential.’

Eagerness to embrace technology prompted the founding of Baltic Yachts in the first place. Johansson was project manager of the Swan 65 when he tried and failed to convince his managers that it could be built lighter, stiffer and better using sandwich construction with unidirectional fibres instead of a single laminate with woven rovings.

The five who left Nautor – boatbuilders Jan-Erik Nyfelt and Nils Luoma, purchasing manager Ingmar Sundelin, designer Tor Hinders and Johansson – became the nucleus of Baltic Yachts.

Baltic Yachts – major milestone boats 1974-2022

1974 Baltic 46 Ahead of its time: tank tests, sandwich construction, unidirectional fibres, balanced spade rudder, epoxy bonded teak deck…

1977 Baltic 39 Most popular model, 74 in six years. From 1980, one of the first yachts to have computer-generated VPP

1979 Baltic 51 Notable for interior design innovations. First double-berth cabin under an aft cockpit, slanted bulkheads for optimal use of space

1982 Baltic 80 Midnight Sun Baltic Yachts’ first maxi racer and one of the first maxis with full glassfibre composite construction.

1985 Baltic 43 Bully The first offshore sailing yacht in the world built entirely with epoxy resin

1996 Baltic 67 Aledoa The first cruising yacht built entirely in pre-preg carbon

1996 Baltic 87 Anny First Baltic with a lifting keel, complex hydraulics and push-button sail controls

1997 Baltic 70 Vittfarne First Baltic yacht to combine classic appearance with hitech construction and modern hydrodynamics

1997 Baltic 70 Loftfari The first yacht with a fully fitted interior built entirely in pre-preg carbon and Nomex honeycomb, all invisible under the teak veneer finish

Baltic 78 Super Baltic 5 Canting keel with its entire mechanism under the cabin sole; 3.5kts faster than the same yacht with a fixed keel

2002 Baltic 147 Visione The first superyacht capable of planing at 30 knots. Packed with unique innovations, ultra-light displacement (105T) and almost literally no expense spared

2003 Baltic 141 Canica A very complex build and fitout with hi-tech materials, construction techniques and systems. The first Baltic ‘super cruiser’

2011 Baltic 197 Hetairos Largest carbon composite sailing yacht in the world at 221ft LOA. Classic look, superb finish. Hi-tech build and hydrodynamics

Baltic 175 Pink Gin The largest full carbon sloop in the world to date. Unique fold-down, through-hull platforms in the saloon and owner’s suite

2019 Baltic 142 Canova First DSS foil on an ocean cruising superyacht. First hybrid drive with full regeneration. Advanced composite engineering. A giant leap into the future

2022 Baltic 68 Pink Gin Verde First Baltic yacht built with 50% flax fibre. Advanced electric/hybrid propulsion, super efficient systems

‘They had a strong belief in themselves, courage to swim upstream and test new ideas,’ Baltic Yachts’ marketing manager Elisabet Holm explains. ‘They all had a passion for boats, a strong driving force to learn new things and research technology, and they were always ready to meet new challenges.’

The original Baltic 46 was far ahead of its time. At a time when nearly all new designs simply relied on the naval architect’s eye, experience and intuition, several different hull models were tank tested across a range of speeds, at various heel and leeway angles before the design of the 46 was finalised and only then was it built. It had a balanced spade rudder and solid rod rigging, which were then used only on hi-tech racing yachts and its teak deck was laid with epoxy resin. But the hull laminate itself was the key innovation.

‘In those days most yards building larger yachts used woven rovings with fibres bent, not straight, hence not structurally optimal and they also resulted in resin concentration,’ Johasson explains.

‘You could see the roving patterns on the surface, due to resin shrinking, so before applying the rovings they used several layers of chopped mat, which has very low structural value, especially on larger yachts, but added a lot of weight.

‘We used a very thin surface cloth and the rest of the laminate was unidirectional fibres, oriented in the direction of the stresses and perfectly straight, hence stronger and stiffer.

‘The fibres we used did not create resin concentration so there was less print-through on the hull surface. Unidirectional does not build up thickness like woven rovings so we used them with a core material in sandwich construction. This achieved much higher panel stiffness than a single laminate and gave us more flexibility for panel sizes.’

End grain balsa was the core for the 46 but Baltic soon switched to foam cores with a variety of densities and strengths. Carbon fibre was used from 1979, initially in rudder posts, beam tops and to reinforce high-stress areas of the hull where extra stiffness was needed. As stabilised foams for high-temperature cures and then Nomex for pre-preg carbon construction became available, Baltic pioneered the use of those materials.

Baltic Yachts’ early achievements belie the fact that it faced strong headwinds right from the start. 1973 was a bad year to launch a new brand of sailing yachts, with the global oil crisis looming.

The yachting industry as a whole was hit hard and by 1977 Baltic had to seek outside investment to stay in business. Ironically that same year saw their first major commercial success, selling 12 Baltic 39s at the Hamburg Boat Show, which was unheard of at the time.

Hollming, a Finnish shipbuilder, acquired Baltic. Two of the founders, Nils Luoma and Ingmar Sundelin, quit but the takeover turned out to be a positive move. Hollming provided stability and investment to help Baltic grow. A huge production hall was built, funds were provided for new model development and marketing.

An unusual aspect of Baltic Yachts that undoubtedly worked in its favour was the dual role of Johansson. It’s rare that the technical guru of a major boatbuilder is also its head of sales and marketing, yet he combined both jobs with great success for 40 years.

Even now, though officially retired, he still frequently offers a guiding hand in the development of new projects and the current EVP, Henry Hawkins, describes him as ‘an unbelievably useful sounding board and wise head’.

Baltic’s in-house designer Tor Hinders made his mark by changing the way boats are fitted out down below. His stand-out innovation, which was met with hostility when introduced in 1979 on the Baltic 51 but has since been copied by almost every sailing yacht builder in the world, was to put a double-berth cabin under an aft cockpit.

Another key factor in Baltic Yachts’ early success was its partnership with the Canadian naval architects C&C Design, whose chief engineer Rob Ball was among the first in the industry to start using computers. From 1980 he supplied VPP – polar curves and tables of numbers – for the Baltic 39, 51 and 37, with detailed instructions on how to use them. Despite being generated by 2D computing (as 3D models were not yet available), Johansson says those first VPP numbers were accurate and useful.

The yard was quick to develop its own computing expertise. ‘As soon as programmable calculators and then the Epson HX-20 computer became available we saw their potential and started to use them,’ Johansson says. ‘There was no software so we did our own coding.’ By the early 1980s they were already using these tools for displacement, flotation and trim calculations, laminate design and rating optimisation.

A huge quantity of data has been compiled since then and the initially simple programs have evolved into a sophisticated suite of software that enables the technical team to make extremely detailed weight and load calculations for the hull and rig of any new design, study engine power, prop pitch and range for electric and conventional propulsion systems, and much more. The yard has never had any ambition to design its own yachts, but is quite often asked by clients to do preliminary studies before a naval architect is appointed.

The 1980s were the peak of series production but Baltic Yachts but they also began pushing the boundaries of performance with custom builds with more scope for creative technical development.

‘A series production model is always to some degree a compromise,’ Johansson says. ‘On custom projects you can take things much further. For very knowledgeable clients looking for performance we have taken things to the edge.’

The 80ft Midnight Sun was one of the first maxis with full composite construction, launched in 1982. ‘The forward part was a large, empty sail store and we used specially designed longitudinal bulkheads and framework in the upper corner between hull and deck to create the required stiffness,’ Johansson recalls.

The Baltic 43 Bully was the first offshore yacht built entirely in epoxy resin, in 1985. In technical terms this was a spin-off from an earlier R&D project, developing ultra-strong vacuum-infused sandwich laminates for a Soviet deep-sea submarine, which ruffled diplomatic feathers when the Americans found out about it. ‘The main unit was solid steel; we built a streamlined cover around the equipment,’ he says. ‘If you send a normal laminate down to 6,000m it will not be the same afterwards. We learned a few things from that project.’

In 1990, Baltic regained its independence. Finland’s industrial sector was in recession and Hollming needed to focus on its core business. ‘They asked us to arrange a management takeover,’ Johansson explains. ‘The yard was an important workplace for the local community and to shut it would have been very destructive. We were 32 employees who got together, took over and continued the business.’

Marketing manager Lisbeth Staffans stepped up to be managing director and led Baltic Yachts for two decades from a challenging start. ‘With a bad order book and uncertain future there were sleepless nights at the beginning of this new era,’ Johansson says. ‘Lisbeth was a very good person for that job. We couldn’t afford to make any mistakes and she made sure we didn’t. But this period is the one I’m most proud of. We did a good job, moved up in the size of our projects and stayed profitable.’

Innovation continued apace with production manager Christer Lill running a remarkably tight operation as the yachts ramped up rapidly in sophistication and size. In 1996 they launched 67ft Aledoa, the world’s first pre-preg carbon cruiser, and 87ft Anny – their first with a lifting keel, twin rudders and complex hydraulics. She had full push-button sail controls and a tender could be driven straight into the automatic opening-andlowering garage in her stern.

The following year, the Baltic 70 Vittfarne heralded a new style of yacht combining classic appearance and fine traditional craftsmanship with hitech construction, light displacement and modern hydrodynamics. ‘Bill Dixon’s team did a fantastic job on the design and our carpenters performed magic in building it,’ Johansson says.

Another Baltic 70, also launched in 1997, took carbon composite sandwich construction to a new level. The fully fitted interior of Loftfari was built almost entirely in pre-preg carbon/ Nomex honeycomb as well as her hull and deck, saving a large amount of additional weight.

It looked traditional, though, with thin veneers and fillets of teak covering all of the composite surfaces. Most Baltic yachts are now fitted out in a similar way.

The 78ft Super Baltic 5, delivered in 2000, was a major feat of engineering with a canting keel whose entire mechanism was installed in the shallow bilge beneath the saloon sole. She was calculated to be at least 3.5kts faster than an identical yacht with a fixed keel.

At the turn of the millennium Loftfari’s owner came back to Baltic with an impossible design brief, ‘or so it seemed at first,’ Johansson says. ‘To build a yacht in excess of 140ft capable of planing at 30 knots or more.’

The project was an immense challenge, not least because their largest build up to then was a 97- footer. Two years of development work followed before the owner gave the green light for the build to proceed. Remarkably the yacht was delivered six months ahead of schedule and exceeded all expectations.

Packed with unique innovations and with almost literally no expense spared, the Baltic 147 Visione was far ahead of her time and despite being 20 years old she is still quite capable of taking line honours in superyacht regattas today.

In build at the same time, the 141ft Canica challenged the yard in different ways. Performance was key but a lot of equipment and systems were also required to ensure a very high level of comfort on board. ‘That was the first yacht we built with a full floating interior,’ Baltic sales director Kenneth Nyfelt, son of founder Jan- Erik, explains.

‘We installed a highly complex Siemens PLC monitoring and control system, and it was the first project where we used noise and vibration consultants.’ With half the displacement of a typical 140ft cruising yacht, the performance targets were achieved and Canica can now be regarded as the first in a gradually evolving style of high-performance Baltic ‘super cruisers’ that continues to this day. A similar and parallel evolution of successful cruiser-racers began with Nilaya in 2010.

A stand-out project delivered in 2011, at 221ft LOA the Baltic 197 Hetairos is largest carbon composite sailing yacht in the world. A true wolf in sheep’s clothing with an incredible sail area : displacement ratio and a regular winner in superyacht regattas, the 60-metre ketch is classic on deck but thoroughly modern below the waterline with a unique lifting rudder as well as a lifting keel.

Around this time, the people who had staged the 1990 management takeover began to retire so new owners were needed. Two local investors bought shares in 2010; three years later an 80 per cent stake in Baltic Yachts was acquired by the German family-owned company Otto Bock – led by Professor Hans Georg Näder, a longstanding client of Baltic Yachts – and its future was secured. Henry Hawkins, a yacht captain with vast practical experience including many thousands of ocean miles as skipper of Näder’s yachts, joined Baltic, taking on a large part of Johansson’s role.

Näder’s own 175ft Pink Gin VI is one of the most notable recent builds and currently the world’s largest carbon composite sloop with a rig 16m taller than a J Class. Her key features include fold-down platforms in her topsides just above the waterline that are large enough to walk through, one amidships in the main saloon and one forward in the owner’s suite.

While relatively easy to build on a large motor yacht, putting large apertures in highly stressed parts of a sailing yacht hull without reducing its stiffness was a major engineering challenge, solved by mechanically locking the platforms firmly in place to become structural parts of the hull.

Another recent showcase of Baltic’s innovation is the 142ft Canova, which made headlines in 2019 as the world’s first superyacht with a DSS foil to reduce pitching and heeling, plus a host of other advanced features such as an immensely strong coachroof with a featherlight look and an electric drive system that provides enough regeneration capability under sail to cross the Atlantic without using any fossil fuel – with both sailing and hotel systems running.

After four years of cruising, a wide range of what used to be bleeding-edge technologies are now proven to work reliably.

To mark Baltic Yachts’ 50th anniversary, the first Baltic 46 Queen Anne returned to the yard last spring for a refit. Two of the men who built her – Johansson and Jan-Erik Nyfelt, whose grandchildren now work at Baltic – were delighted to find her in excellent condition, which a survey duly confirmed.

‘No structural works are needed, the hull appendages are sound, as is the mast,’ Hawkins says. ‘It’s also interesting that the original propulsion setup was still operational and in good order. The enjoyment at our end was the size of everything compared to today, from fibre technology to deck fittings. There are 18 winches on that boat; a modern 100-footer uses just seven or eight!’ She will be relaunched in June after a cosmetic refit, with a new engine.

What direction is Baltic Yachts likely to take in the future? The 68ft cruiser-racer Pink Gin Verde might hold a few clues with its 50 per cent flax fibre hull and micro-turbine hybrid propulsion system, but as Baltic’s CEO Anders Kurtén puts it, ‘That all depends on where our customers want to take us.’

‘We are fortunate and honoured to build some of the most exciting, groundbreaking custom sailing yachts in the world which means the next major milestone will forever be the next launch, summer 2023 being a perfect example,’ he says. ‘My best guess for the future is ever increasing sustainable practices and yachts with diminishing lifecycle emissions, as well as quantum leaps in terms of pure sailing performance.’

Click here for more information on Baltic Yachts

The global authority in superyachting

- NEWSLETTERS

- Yachts Home

- The Superyacht Directory

- Yacht Reports

- Brokerage News

- The largest yachts in the world

- The Register

- Yacht Advice

- Yacht Design

- 12m to 24m yachts

- Monaco Yacht Show

- Builder Directory

- Designer Directory

- Interior Design Directory

- Naval Architect Directory

- Yachts for sale home

- Motor yachts

- Sailing yachts

- Explorer yachts

- Classic yachts

- Sale Broker Directory

- Charter Home

- Yachts for Charter

- Charter Destinations

- Charter Broker Directory

- Destinations Home

- Mediterranean

- South Pacific

- Rest of the World

- Boat Life Home

- Owners' Experiences

- Interiors Suppliers

- Owners' Club

- Captains' Club

- BOAT Showcase

- Boat Presents

- Events Home

- World Superyacht Awards

- Superyacht Design Festival

- Design and Innovation Awards

- Young Designer of the Year Award

- Artistry and Craft Awards

- Explorer Yachts Summit

- Ocean Talks

- The Ocean Awards

- BOAT Connect

- Between the bays

- Golf Invitational

- Boat Pro Home

- Pricing Plan

- Superyacht Insight

- Product Features

- Premium Content

- Testimonials

- Global Order Book

- Tenders & Equipment

Path: On board Baltic's award-winning 45m sailing yacht

Inspired by an experienced sailor, the World Superyacht Award-winning sloop Path is a real standout, as Sam Fortescue finds out in Palma...

It takes an effort to stand out from the crowd in Palma. There are so many metres of gleaming superyachtery lined up on the quays that everything starts to look the same. Not so the latest launch from Baltic Yachts . It has the advantage of a mast, which naturally helps in a world dominated by motor yachts. But it is really the sleek, quiet purpose of 44.6 metre Path that distinguishes her. That and the flame orange crew uniforms.

With a German designer, an obsessive Finnish builder and an engaged owner, nothing on this boat has been left to chance. I am immediately grateful for the owner’s foresight as I step aboard on an uncharacteristically grey morning. With the leaden threat of rain, we congregate under the truly vast hardtop he requested, which protects the dining and lounging areas of the cockpit. It is a continuation of the coachroof, which sweeps aft a further seven metres.

“The owner took all the experience he gained from sailing round the world and put it into the new boat,” explains Henry Hawkins, executive vice president of Baltic Yachts. “His previous boat was a Baltic 112 which we call Old Path . He’s a hugely passionate sailor and competes in a couple of sports boat classes. So he was adamant he wanted a cruising boat with performance.”

And what the hardtop lacks in pure elegance, it makes up for in sheer practicality. It is just one part of the owner’s philosophy of choosing reliability over elaborate technology or flashy styling, as designer Rolf Vrolijk notes. “This owner knows very well what he wants. There was no need to go to an external designer to make a statement.”

Ease of handling was the other key brief for the judel/vrolijk team. Path has twin rudders, for instance, and a hydraulic lifting keel. This reduces her draught to 3.4 metres – enough to get into many smaller ports and anchorages, including much of the Bahamas. She also features a roller boom system from Carbo Link to make light work of furling or reefing the 558-square-metre mainsail.

On the mechanical side, she is equipped with a saildrive pod system that can rotate through 340 degrees beneath the boat to give optimum thrust and torque at almost any angle. Coupled with the bow thruster, this flexible system simplifies close quarters manoeuvring. A four-blade variable-pitch propeller also adds to efficiency across long passages under power or when motor sailing.

“When manoeuvring under power, you can set it to a high engine speed to provide hydraulic power to the thruster via a PTO,” Hawkins says. Only one thruster is needed with the rotating saildrive, he explains. “We can then add a little pitch to the blades to move forward or backwards or even sideways as needed, as this leg rotates.”

Path rows somewhat against the current with its engine. The capable 550hp Scania unit is certainly up to the job, but the power system eschews hybrid or battery-assisted technology. It is an old-fashioned mix of iron, oil and diesel with enough grunt to pull the boat along and turn the winches, while a pair of 55kW Northern Lights generators pick up the hotel loads. Of course, that is exactly what the owner wanted.

“We looked at electric propulsion, as with the majority of our boats,” Hawkins says. “But Path is set up as a world cruiser and the cornerstone had to be proven reliability.” Similarly, the Hundested main thruster pod is theoretically capable of retracting into the hull to reduce drag under sail. “The owner chose not to take the folding ability for the sake of simplicity,” he adds. “While the pod and propeller hydraulics can all be driven mechanically to return to port.”

Before anything else, though, this boat is a Baltic, and that means a fast hull with a meticulous layup in carbon fibre. By making ample use of Sprint and pre-preg materials from Gurit, Baltic has limited the displacement of this 44.6-metre yacht to 172 tonnes. Pre-preg means that precisely the right amount of epoxy resin is already right where it needs to be in the layup, eliminating the wastage of wet systems.

The lines by judel/vrolijk are as sleek as you would expect from a team that has done so much work with racing yachts. Despite her length, her beam tops out at 9.35 metres, giving Path naturally efficient proportions. The architecture is closely related to that of the Baltic 112 Canova . “These are families of hulls developed through feedback from the crew,” Vrolijk says.

A powerful masthead sloop rig gives the crew plenty of options, and again, the emphasis is on ease of handling. “We didn’t want to go too big with a square-head main, because that creates too much complexity for a cruising guy,” Vrolijk says. No fewer than two fixed and two removable headstays permit a range of sails upwind, plus a three-metre bowsprit for setting the gennaker or dedicated reaching sail. Baltic describes the set-up as a homage to the Imoca 60, whose multi-headsail configuration make short-handed racing a reality.

Vrolijk says that the boat sails well with two headsails set – jib and staysail or storm jib and staysail, as conditions dictate. The main is reefed by putting turns on the boom, but in order not to overstrain the mandrel, the sail still has three reefing points on the luff and leech that take the strain. After sea trials in Palma, he described Path ’s handling in typically dry fashion. “It was, of course, quite nice,” he told me. “She has a balanced rudder feel, and the boat tracks very well.”

Path is designed to sail at between 11 and 16 knots in typical conditions, but she had already hit speeds approaching 20 knots on the passage down from Finland, according to Captain Daniele Cesaro. In Palma, the boat handled 35-knot gusts under full main and a staysail jib.

Sightlines from the two wheels are well thought out, with a clear view ahead down the windward side. Each helm station has its own little hardtop with a glass panel for gazing at the sail. It feels a little like the bridge of the USS Enterprise sitting here with six big Sailmon screens for boat data and six huge glass-bridge displays.

Step inside, though, and you instantly return to a past where wood, not carbon fibre, was king. With decidedly classic styling, the interior is all about panelled walls and solid furniture. Elegant cabinetry is well endowed with fiddles – this is an owner who understands the need to steady yourself as you cross the saloon on a 20-degree heel. From sofas to a robust wooden swivel chair at the navigation station, it seemingly adds weight, but says Hawkins, the furniture is foam core with a wood veneer, which allows keeping the weight under control.

Margo Vrolijk led the styling team, making it a full house for judel/vrolijk. She drew on a visit to the owner’s home and a good look at his previous Baltic. “The concept is inspired by how the family lives ashore and translating that into an easily controlled sailing yacht,” she says. “The timeless style of the interior has been achieved through symmetry in geometry and balancing the choice of neutral and natural colour palettes with classic, colourful patterns like stripes and paisley shapes.”

This approach has created a very liveable environment below, with deep, inviting sofas, plump mattresses and comfy chairs. Despite the suede and natural fabric finishes, the upholstery has been designed to be easily maintained when off the beaten track. Most surfaces are in warm teak, while the floors are in a dark stained oak that will conceal wear and tear. “You can spill anything on the fabrics and it will still remain the same colour,” says Margo Vrolijk.

More than the materials, though, it is the spaces created by the design team that intrigue. Beneath that huge main saloon lie the owner’s quarters, bang amidships. The cabin spans the full beam but is partially divided near the middle by a glass screen. Twin beds lie to starboard, with access to a large bathroom with both a shower and recessed full-length bathtub.

To starboard is a wonderful kind of parlour or snug sitting room, with two Poltrona Frau recliners and a host of convenient features within reach. Touch a button and the glass panel turns opaque, becoming a screen for projecting charts and nav information. Pull open a low cabinet and there’s a custom-built recess for a decanter of whisky and weighted crystal tumblers. The glasses are inlaid with a magnet on the base to keep them from sliding off when set down. Pilot guides and reference books line the walls – a library for settling down with a drink to figure out where to head next.

Upstairs you reach the office, on a kind of half level. A huge array of electronics is concealed behind the panelling here, while twin VSAT domes can keep the owner as connected on board as he would be if he were sitting in the office. “The system is Starlink ready,” Hawkins says. “Then there’ll be no need for those big domes – the eggs in the rigging will disappear.”

As this space lacks a hull window, the owner requested an LED wall, the first I have seen aboard a yacht. Running the length of the hull in the office, it normally displays an aquarium scene, but can naturally be programmed to show anything. Vrolijk mocked up a full-size office and owner’s cabin to check every detail.

Although naturally on a smaller scale to the owner’s cabin, three en suite guest cabins offer heaps of space. A VIP cabin in the bow converts between double and twin and includes its own sofa area for privacy. The double just aft has an even larger snug seating area opposite. And a final guest double is in the aft accommodation. Though this puts it next to the crew area, it has its own private companionway to the saloon.

There are lots of little features which are a pleasure to discover. I liked the way that a navigation display folds up out of a burnished chart desk in the main saloon, for instance. Another display in the crew mess slides down out of an overhead cabinet to create a barrier between the navigator and the mess. It’s a smart idea that creates two distinct spaces when necessary. I also like how the doorknobs are leather bound.

With her huge aft deck and a big bathing platform for catching the sun, plus a tender well on the foredeck that serves as a pool when the Ribeye YT600 has been craned out, Path can hold her own in Mallorca and the world’s other yachting hotspots. But she won’t be here for long. Though she’s registered in Malta, this boat has no home port – no marina berth with her name on it. Her calling is as an ocean wanderer. She is going to find her own path around the world.

First published in the June 2022 issue of BOAT International. Get this magazine sent straight to your door, or subscribe and never miss an issue.

More about this yacht

Similar yachts for sale, more stories, most popular, from our partners, sponsored listings.

- Service & Refit

- Baltic Yachts Rendezvous

LEGENDARY BALTIC 39 PANGAEA

19 november 2021.

Record-setting Baltic ownership in Washington State

Mac Madenwald has owned his Baltic 39 Pangaea from new since 1978 and at the age of 81 he and his wife Wendy still race and cruise 90 days a year from their home port of Anacortes

When Mac Madenwald was trading up from his Gary Mulldesigned Ranger 33 back in 1977 his intention was to buy a C&C 40, but a strike at the boat builder and a chance sighting of the new Baltic 39 in a brochure at his local brokerage office set him on another course.

Mac on Pangaea’s foredeck anchored in the Broughton Island archipelago in British Columbia

Friends in Europe checked out the 39 at the Düsseldorf Boat Show and following rave reviews Mac bought hull number five unseen. Pangaea was shipped to Vancouver, British Columbia before being transported to Seattle for commissioning – after a telephone call to say his new yacht was on its way, he even followed the truck down the local highway as Pangaea headed for her new home port!

There’s clearly something about longevity which attracts Mac, a retired orthopaedic surgeon. He and his wife Wendy, who he met when she was crewing on another Baltic, are members of the second oldest yacht club in Washington State. The Anacortes YC was founded in 1891 making it the 4th oldest on the US west coast. And he named Pangaea after the supercontinent which eventually divided to form the geographical world we know today, 335 million years ago.

Mac and Wendy sail 90 days a year in the yacht Mac bought back in 1978

To cap it all, when Mac was invited to Jakobstad on occasion of Baltic Yachts’ 30th anniversary party in 2003, he was recognised as the longest continuous owner of a Baltic yacht worldwide. And it’s an accolade he has no intention of giving up any time soon!

Mac and Wendy continue to take part in the yacht club’s Wednesday evening ‘beer can’ races, they have completed two 2500nm Victoria to Maui races and they take advantage of the fantastic cruising grounds in the San Juan Islands, further north in British Columbia’s Salish Sea and south towards Olympia in Puget Sound.

The fabulous backdrop of Mount Baker, 10,800ft, in the Cascade mountain range in Washington State, as Pangaea sails in waters close to her home port of Anacortes

“We’re a social kind of boat and love having people aboard,” said Mac who is particularly keen to get younger people afloat so that they can experience sailing and learn. In fact, so many people have sailed with Mac that some friends presented him with a licence plate which read “Honk if you’ve sailed on Pangaea”. And as a family yacht Mac says: “She’s brought up two children, three grand-children and counting!”

Sharing their enthusiasm for sailing with the next generation, Heath and Yarrow Voegtlin, two o of their grandchildren

Mac and Wendy keep Pangaea afloat in the Port of Anacortes Marina all year round and are out cruising or racing 90 days a year. “The boat has remained in great condition and the only item that might need attention soon is the teak deck – we’ve replaced the cockpit seating teak, but the rest is original,” said Mac.

One mishap occurred at the beginning of Pangaea’s life when the Saildrive leg completely corroded away due to a commissioning mix up. “We hadn’t seen many Saildrive legs out here back then and the leg wasn’t protected by an anode,” explained Mac. “But Baltic and Volvo were great and they came over here and sorted everything out – we haven’t looked back!”.

Mac and Wendy spend a lot of time cruising in the beautiful San Juan Islands archipelago in the State of Washington lying between Anacortes and Vancouver Island

We’re constantly updating our website to bring you news of launchings, new commissions and Baltic inspired innovation.

Lifestyle I

A family affair: the baltic yachts rendezvous 2023, words: tide | images: oli riley.

September saw a special spectacle take place just off the shores of Sardinia: a vision of the latest Superyachts sailing alongside modern classic 1970s sailboats. The occasion? A four-day celebration of everything that Baltic Yachts has achieved in its half-century history so far. More guests than ever before came together, including owners, service and refit friends and industry figures – such as ourselves at TIDE – for a long weekend of sailing and feasting on fantastic Italian food, in this, the culmination of Baltic’s extended anniversary event, known as the Rendezvous.

Baltic Yachts has generated such a large, loyal client base thanks to the fact that the Finnish brand is one of the last purely custom yacht builders that works with owners and architects, incorporating modern approaches and the latest technology. Strong family connections within the yard also resonate with owners, providing a sense of community and an enjoyable build experience, as showcased by the fact that so many of them wished to both support the company and spend time with each other.

The location? Porto Rotondo, a yacht club enveloped by lush landscapes and white-sand beaches, leading to cobblestone streets and towns fizzing with energy. However, the dock was the most important place to witness during this weekend, lined with Baltic’s latest builds alongside its heritage designs, offering a one-off window into 50 years of sailing innovation. Twenty-six yachts graced the event, to be exact, spanning from the vintage Baltic 33’ of 1976 to the ultra-modern Path, a 146’ built in 2021.

Mingling between owners and crew kicked off during registration, before everyone sat down together to a welcome dinner that extended into the evening. While the Captains’ Meeting the following day hinted at the competitive spirit within the Baltic family, the atmosphere shifted to smiles and cheers as everyone headed to their yachts. The first day unfolded with a light air, and the boats presented a stunning scene as they sailed through the course. Day two brought a stronger breeze and heightened action, creating ideal conditions for enjoyable, all-level sailing. Attendees then celebrated the winners under the Sardinian stars, honouring the Baltic team. Although PG, Baltic’s founder, couldn’t be there in person, his inspiring speech played out via a screen, in which he emphasised the unity he knew was being experienced throughout the weekend and beyond.

Sunday began with a packed breakfast scene, the espresso machine working overtime, followed by a long and lazy beach barbecue. The common conversation? When would all those at this Rendezvous, rendez-vous once more? A talking point that underlined the authentic and social spirit of this special weekend away with the loyal and far-reaching Baltic family.

Further Reading

Travel I number 07

The kamalame cay.

Under the careful watch of the Hew family, an untouched strip of sand in the Bahamas was transformed into Kamalame Cay, a laidback private-island resort

Design I number 07

From land to sea.

Featuring a contemporary, warm and crafted look by Swedish architects Andreas Martin-Löf Arkitekter, the 34m sailing yacht ZEMI is a fine example of how shore-side designers can adapt to create stunning, boundary-pushing yacht interiors

Environment I number 07

Dominica and the whales.

With a massive decline in the global Sperm whale population caused by a combination of hunting, pollution and climate change, the species is in grave danger. But things are set to change thanks to an ambitious plan by an unlikely ally

- Destinations & Hotel Guide

- NEWSLETTER Sign up!

- MAGAZINE Subscribe!

Baltic Yachts | What’s going on in Finland

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]irst presented at the 2017 Düsseldorf Boat Show, Baltic Motor Yachts is a new division of Baltic Yachts, the shipyard situated in Ostrobothnia, Finland, a region steeped in eight centuries of fine ship and yacht building history. Baltic Yachts, renowned for its sailing yachts and exceptional levels of engineering and build technology, with light displacement, quiet running and true seaworthiness at the heart of luxury comfort and ease of operation, is now ready to extend these attributes into the luxury motor yachting sector and for the occasion introduces two new ranges of individually tailored motor yachts: the Motor Yacht range with the 27-metre Baltic MY88, 34-metre Baltic MY112 and 41-metre Baltic MY135; and the Day Boat range with the 15-metre Baltic MY49 and 17-metre Baltic MY56.

This new range development is driven by requests from current owners seeking diversity and requiring the same high-end finish detail and craftsmanship, and is also inspired by Baltic’s recent, restoration of the delightful 25m/82ft motor cruiser Sunny Day for the company’s owner, Professor Hans Georg Näder, a serial Baltic yacht owner himself. This new programme comes also at a time when Baltic Yachts has a full forward order book for sailing yachts, so marks a significant new capital investment and development in the company’s growth.

“We are leaders, not followers,” says Professor Näder . “The Baltic Yachts name conveys quality, prestige and performance, and Baltic Motor Yachts extends this experience and reputation into a new area of yachting. The refit of our family motor yacht, Sunny Day, stimulated me also to initiate our own Ligurian styled motor yacht line, using our superb facilities and state of the art technologies for safe reliable motor cruising with superb quality, as we have done for decades in sailing.”

As to the sailing yachts production, orders for three new carbon composite performance sailing yachts measuring between 85ft and 142ft have filled the order book at Baltic Yachts as the company prepares to launch Pink Gin VI , the biggest carbon composite sloop in the world.

Baltic Yachts CEO Henry Hawkins said that in tough market conditions over recent months the company had appealed to a number of clients. “This success is a result of a dedicated Baltic Yachts team effort building on our expertise in the custom sailing yacht arena,” he said. The new projects (Baltic 85 Custom, Baltic 112 Custom, Baltic 142 Custom) , which will start building in 2017, involve world-leading designers and stylists some of whom are new to Baltic Yachts, among them award-winning naval architect Malcolm McKeon and renowned interior specialists Mark Whiteley and Lucio Micheletti. The Baltic Yachts Family very much looks forward to working with this new injection of talent now and in the future.

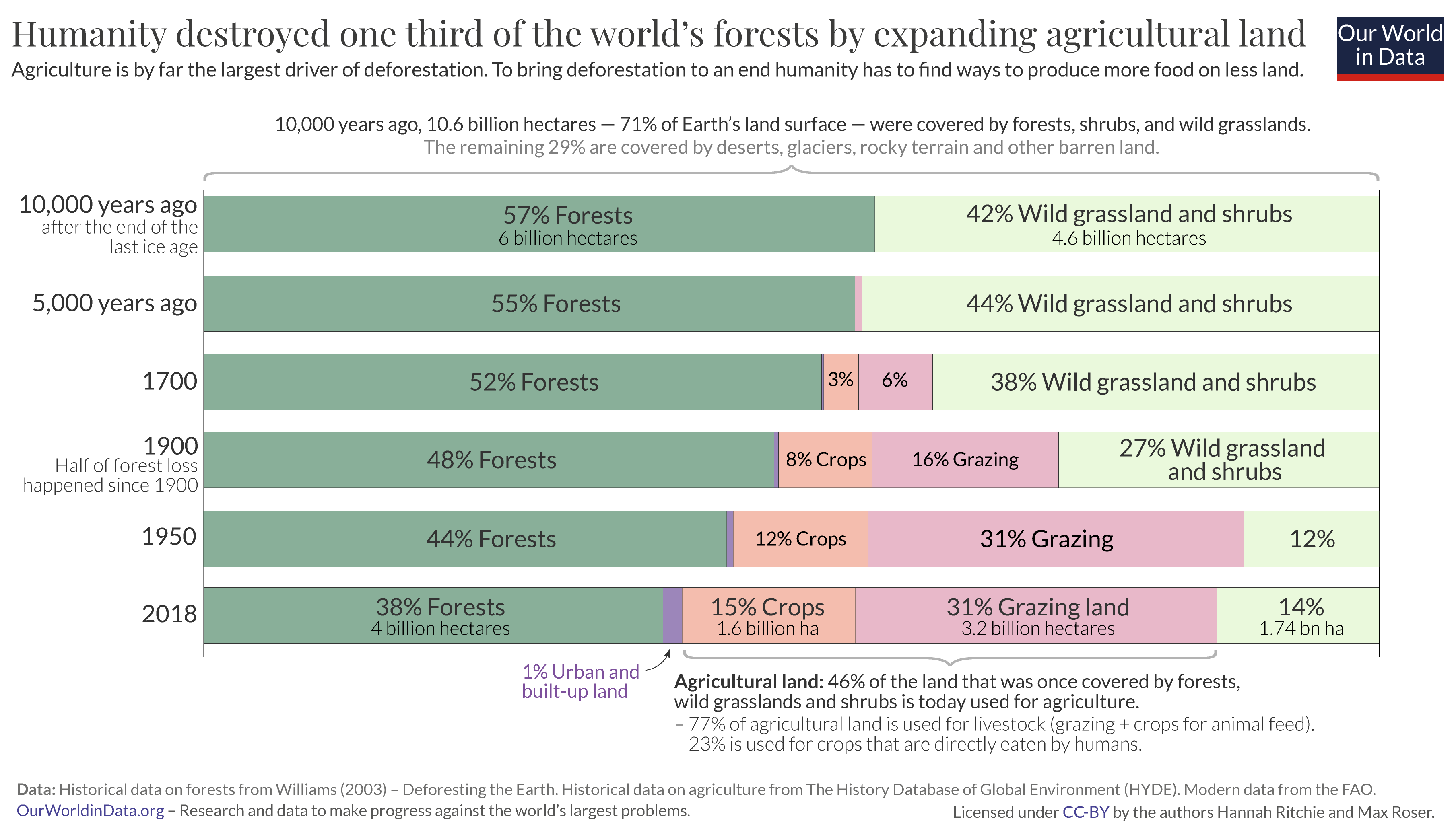

presentation about deforestation

Encyclopedic entry.

Deforestation.

Deforestation is the intentional clearing of forested land.

Biology, Ecology, Conservation

Trees are cut down for timber, waiting to be transported and sold.

Photograph by Esemelwe

Deforestation is the purposeful clearing of forested land. Throughout history and into modern times, forests have been razed to make space for agriculture and animal grazing, and to obtain wood for fuel, manufacturing, and construction.

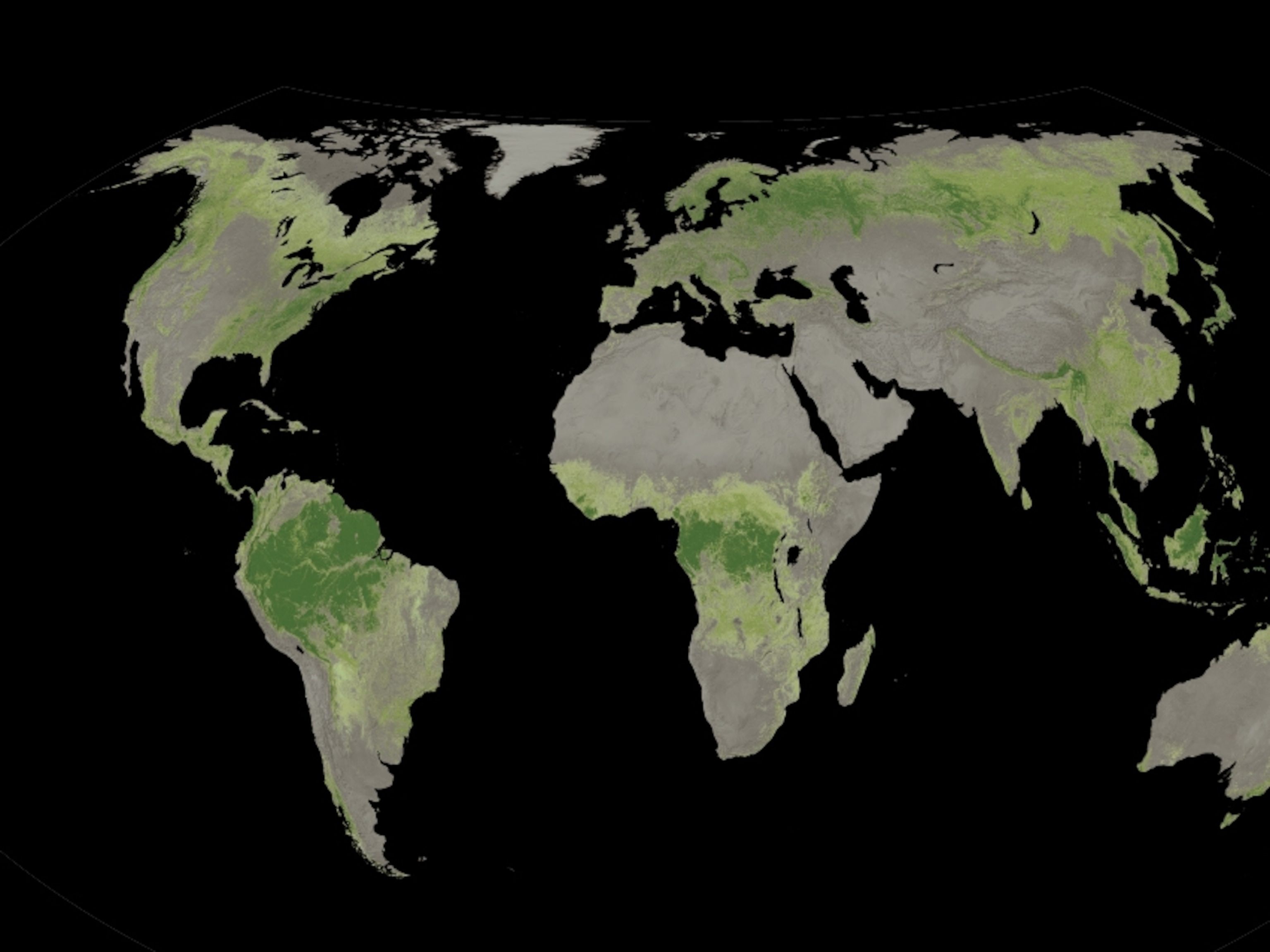

Deforestation has greatly altered landscapes around the world. About 2,000 years ago, 80 percent of Western Europe was forested; today the figure is 34 percent. In North America, about half of the forests in the eastern part of the continent were cut down from the 1600s to the 1870s for timber and agriculture. China has lost great expanses of its forests over the past 4,000 years and now just over 20 percent of it is forested. Much of Earth’s farmland was once forests.

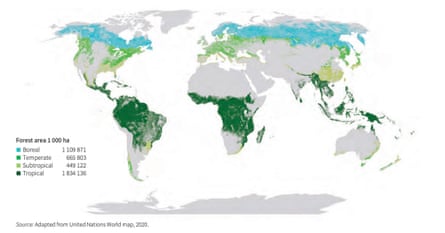

Today, the greatest amount of deforestation is occurring in tropical rainforests, aided by extensive road construction into regions that were once almost inaccessible. Building or upgrading roads into forests makes them more accessible for exploitation. Slash-and-burn agriculture is a big contributor to deforestation in the tropics. With this agricultural method, farmers burn large swaths of forest, allowing the ash to fertilize the land for crops. The land is only fertile for a few years, however, after which the farmers move on to repeat the process elsewhere. Tropical forests are also cleared to make way for logging, cattle ranching, and oil palm and rubber tree plantations.

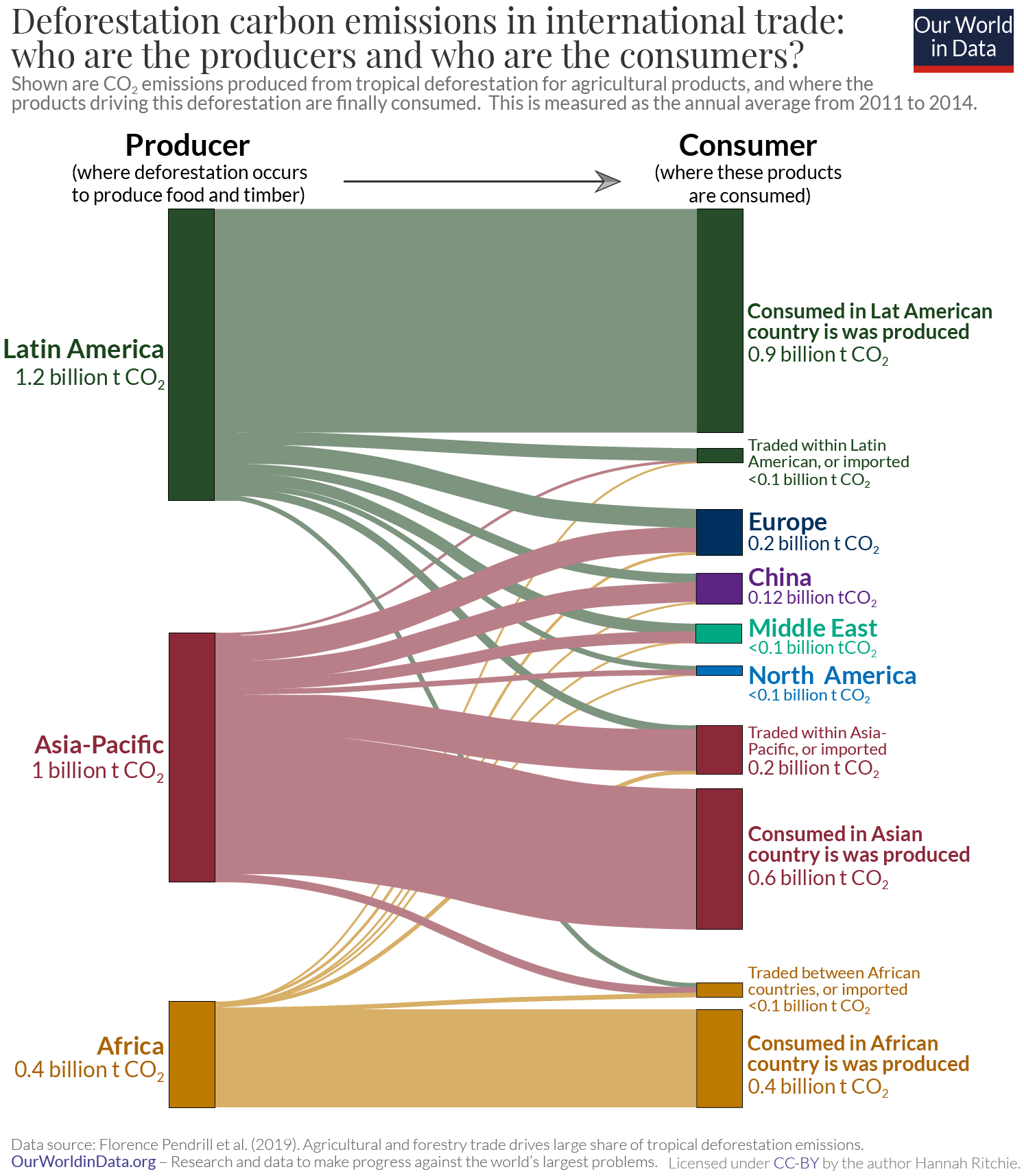

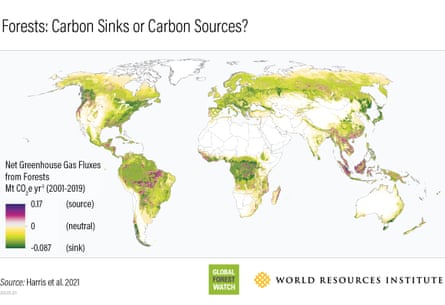

Deforestation can result in more carbon dioxide being released into the atmosphere. That is because trees take in carbon dioxide from the air for photosynthesis , and carbon is locked chemically in their wood. When trees are burned, this carbon returns to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide . With fewer trees around to take in the carbon dioxide , this greenhouse gas accumulates in the atmosphere and accelerates global warming.

Deforestation also threatens the world’s biodiversity . Tropical forests are home to great numbers of animal and plant species. When forests are logged or burned, it can drive many of those species into extinction. Some scientists say we are already in the midst of a mass-extinction episode.

More immediately, the loss of trees from a forest can leave soil more prone to erosion . This causes the remaining plants to become more vulnerable to fire as the forest shifts from being a closed, moist environment to an open, dry one.

While deforestation can be permanent, this is not always the case. In North America, for example, forests in many areas are returning thanks to conservation efforts.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

February 21, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Deforestation 101: everything you need to know.

Earth has lost more than 1 billion acres of forest to deforestation since 1990. Image: Unsplash/roya ann miller

Cristen Hemingway Jaynes

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Forests is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- Deforestation is the clearing of forested land with the purpose of converting it for use in another way, such as agriculture, mining or raising livestock.

- Earth has lost more than 1 billion acres of forest to deforestation since 1990.

- Here’s a round-up of key facts and impacts related to deforestation.

What is Deforestation?

Trees have been around for about 370 million years. Today, there are about three trillion trees and ten billion acres of forest on Earth. That may sound like a lot, but the planet has lost more than one billion acres of forest to deforestation since 1990.

Deforestation is the clearing of forested land with the purpose of converting it to be used for something other than forest, including the raising of livestock , agriculture, mining, development or other non-forest uses.

The biggest human causes of deforestation are farming , especially unsustainable practices such as slash-and-burn agriculture — where forests are burned and cleared for planting — raising cattle for dairy and meat and the uncontrolled cultivation of crops like rubber and palm oil .

Quick Facts

- More than 30 percent of the Earth’s land is covered by forests.

- The Earth loses about 38,610 square miles of forest every year.

- Ninety-six percent of global deforestation occurs in tropical forests .

- More than half of the planet’s tropical rainforests have been destroyed or degraded.

- Due to deforestation, as many as 28,000 species are predicted to become extinct by 2050.

- Forty-one percent of deforestation can be attributed to the clearing of land for cattle and other livestock, with 80 percent of that land located in the Amazon .

- Nearly half of tropical deforestation occurs in Indonesia and Brazil .

- Twelve percent of deforestation is due to soy production, and most soy produced globally is used for animal feed.

- Palm oil, used in products from chocolate and cookies to potato chips, is a major contributor to deforestation.

- More than 100 countries have made a commitment to end and reverse deforestation by 2030.

Have you read?

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} protect, manage, restore: the formula for ending deforestation, china's unique opportunity to tackle deforestation, to tackle deforestation we need to focus on land use. here's why, why should we care about deforestation.

Human Impacts

The ancient forests of our planet have been evolving for thousands of years to provide individualized habitats for millions of species of plants and animals. Millions of people also call Earth’s forests home, and their survival and livelihoods depend on them.

The livelihoods of an estimated 1.6 billion people are dependent on forests, while forests are essential for the subsistence of 60 million Indigenous Peoples.

The choices we make in what we consume, buy and support have a direct impact on the world’s forests. We can’t afford to continue to destroy such an essential part of the health of our planet.

Halting deforestation is essential to avoiding the worst effects of global climate change.

The destruction of forests creates almost as much greenhouse gas emissions as global road travel, and yet it continues at an alarming rate.

In 2012, we brought together more than 150 partners working in Latin America, West Africa, Central Africa and South-East Asia – to establish the Tropical Forest Alliance 2020 : a global public-private partnership to facilitate investment in systemic change.

The Alliance, made up of businesses, governments, civil society, indigenous people, communities and international organizations, helps producers, traders and buyers of commodities often blamed for causing deforestation to achieve deforestation-free supply chains.

The Commodities and Forests Agenda 2020 , summarizes the areas in which the most urgent action is needed to eliminate deforestation from global agricultural supply chains.

The Tropical Forest Alliance 2020 i s gaining ground on tackling deforestation linked to the production of four commodities: palm oil, beef, soy, and pulp and paper.

Get in touch to join our mission to halt to deforestation.

Climate Impacts

Earth’s rainforests remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis, stabilize the Earth’s environment and act as carbon sinks by storing the carbon in their wood and soil. One of the most devastating results of deforestation is that, due to the loss of trees, the enormous amount of carbon they have sequestered gets released back into the atmosphere.

Some tropical forests now release more carbon than they capture, meaning that they no longer operate as carbon sinks.