A yacht going astray in China (6)

I believe the answer is:

' china ' is the definition. (historical name for China) ' a yacht going astray in ' is the wordplay. ' going astray ' is an anagram indicator. ' in ' indicates putting letters inside. ' yacht ' anagrammed gives ' cathy '. ' a ' put into ' cathy ' is ' CATHAY '.

(Other definitions for cathay that I've seen before include "China - antique" , "Name for China in medieval times" , "Old name for China with a feline to start" , "China long ago" , "Ancient China" .)

Taiwan says China seizes fishing boat near its coast

- Medium Text

Sign up here.

Reporting by Ben Blanchard and Yimou Lee; Additional reporting by Ananda Teresia in Jakarta, Bernard Orr in Beijing and Andrea Shalal and Kanishka Singh in Washington; Editing by Josie Kao, Clarence Fernandez and Deepa Babington

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

Thomson Reuters

Yimou Lee is a Senior Correspondent for Reuters covering everything from Taiwan, including sensitive Taiwan-China relations, China's military aggression and Taiwan's key role as a global semiconductor powerhouse. A three-time SOPA award winner, his reporting from Hong Kong, China, Myanmar and Taiwan over the past decade includes Myanmar's crackdown on Rohingya Muslims, Hong Kong protests and Taiwan's battle against China's multifront campaigns to absorb the island.

World Chevron

Storm Beryl spares Mexico's Yucatan beaches, takes aim at Texas

Tropical Storm Beryl was blowing out to the Gulf of Mexico on Friday afternoon and appeared likely to reach Texas by late Sunday, after its strong winds and heavy rain largely spared Mexico's top beach destinations.

Taiwan says China seized fishing boat near Chinese coast

Taiwan demands Beijing release crew and vessel seized from outside Taiwanese waters near Kinmen Islands.

Chinese coastguard officials have seized a Taiwanese fishing vessel and steered it to a port in mainland China, Taiwan has said, urging Beijing to release the boat and its six-member crew.

The move late on Tuesday came as China’s coast guard has stepped up patrols around Taiwan’s Kinmen islands after a series of deadly fishing accidents, one of which led to bitter blame-trading between the two sides.

Keep reading

Indonesian migrant worker band in taiwan puts ‘system of slavery’ on notice, indonesia says will deport 103 taiwanese suspected of cybercrimes in bali, world’s largest maritime drills begin in an increasingly tense asia pacific, china’s communist party expels ex-defence ministers over corruption charges.

Taiwan’s coast guard said the Taiwanese boat was fishing for squid outside Taipei-controlled waters off the Kinmen islands, when it was boarded and seized by two Chinese maritime administration boats.

Kinmen sits next to the Chinese cities of Xiamen and Quanzhou is roughly five kilometers (3 miles) from the Chinese mainland.

The Taiwanese boat was operating during China’s no-fishing period, the coastguard said, adding that Taiwan will communicate with China and urge them to release the fishermen as soon as possible.

China’s Taiwan Affairs Office did not immediately comment.

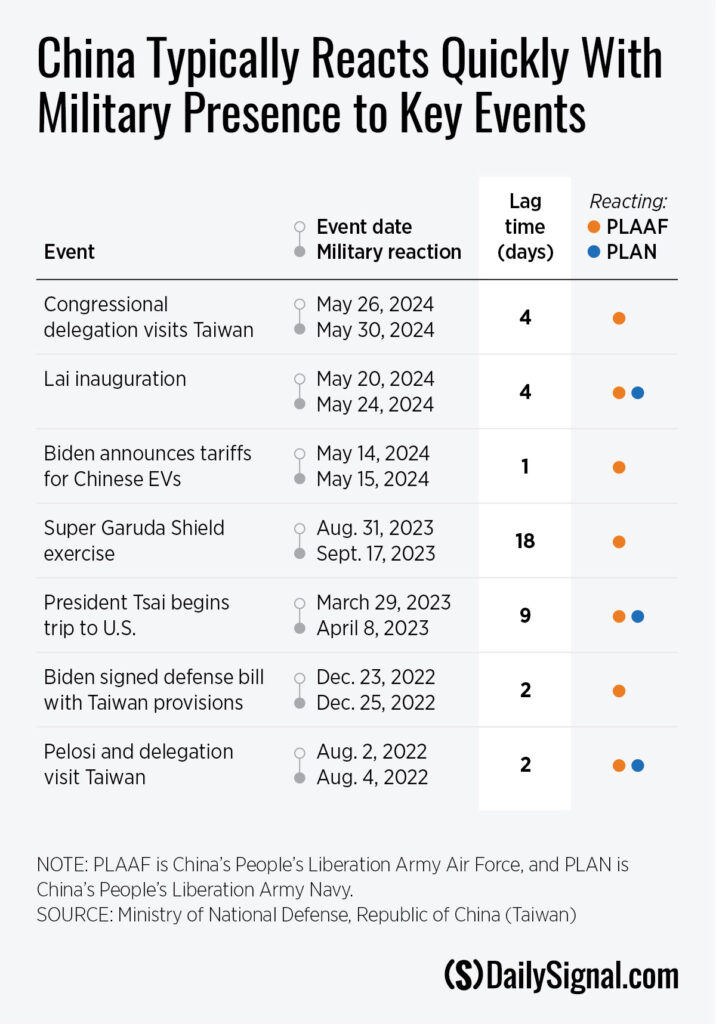

China views democratically governed Taiwan as its own territory and has ramped up pressure on Taipei since President William Lai Ching-te took office in May, a man Beijing accuses of being a “separatist”.

Taiwan’s coastguard said it dispatched two patrol vessels “to try to rescue” the fishing boat, along with a third for assistance, but one was “blocked by” Chinese coast guard ships.

“We broadcast to the Chinese coast guard ship, demanding the immediate release of our fishing boat. The Chinese side also broadcast to us, asking not to interfere,” it said.

“To avoid escalating the conflict, we have decided to stop the chase,” the coast guard said, adding the fishing boat was taken to China’s Weitou port.

The boat had six crew onboard, including the captain and several migrant workers from Indonesia, according to Taiwan’s official Central News Agency.

Taiwan Coast Guard Administration Deputy Director-General Hsieh Ching-chin told reporters in Taipei that China should explain why it had seized the boat, and pointed out that in previous cases, fishermen had been released after paying fines when operating during China’s no-fishing season.

Taiwanese fishing boats need to raise their alert level and the coastguard will also strengthen its patrols, he added.

“The coastguard also calls on the mainland side not to use political factors to handle this situation,” Hsieh said.

Judha Nugraha, the director for citizen protection at Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, told the Reuters news agency that the country’s consulate general in Guangzhou will assist the detained Indonesians.

This is not the first time a Taiwanese fishing boat has been taken by Chinese authorities after operating in that country’s waters, an official said, speaking on condition of anonymity given the sensitivity of the situation.

A Taiwan official, who is familiar with the island’s security planning, told Reuters they have issued alerts to fishing and transport authorities around Taiwan to pay attention to “possible risks” amid frequent Chinese coastguard activities in the region, including near Japan and the Philippines.

It is not uncommon for Taiwan and China to detain each other’s trespassing fishing boats. So far this year, Taiwan has detained five such boats from China, Taiwan’s coastguard data shows.

Chinese maritime enforcement and coastguard ships have been regularly operating around Kinmen since February after two Chinese fishermen died trying to flee Taiwan’s coastguard.

We've detected unusual activity from your computer network

To continue, please click the box below to let us know you're not a robot.

Why did this happen?

Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy .

For inquiries related to this message please contact our support team and provide the reference ID below.

Taiwan Says It Was Warned by China to Not Interfere in the Detention of Taiwanese Boat Crew

Taiwan says China warned its coast guard against interfering in the detention of a Taiwanese fishing boat in what is seen as Beijing's latest attempt to assert its territorial claims in the Taiwan Strait

Chiang Ying-ying

Coastal Control Division Chief Liao Yun-Hung talks about a fishing boat intercepted by Chinese vessels Tuesday night, during a news conference in Taipei, Taiwan, Wednesday, July 3, 2024. Taiwan is calling for the release of a fishing boat after it was boarded by China''s coast guard and steered to a port in mainland China on Tuesday. (AP Photo/Chiang Ying-ying)

TAIPEI, Taiwan (AP) — Taiwan said Wednesday that China warned its coast guard against interfering in the detention of a Taiwanese fishing boat, in what was seen as Beijing's latest attempt to assert its territorial claims in the Taiwan Strait.

The incident comes as tensions have risen following the election of Taiwanese President William Lai Ching-te, whose party rejects unification with the mainland, and an apparent threat by Beijing to execute supporters of Taiwanese independence.

Liu Dejun, a spokesperson for China's coast guard, said Wednesday that the Taiwanese fishing boat was detained on suspicion of illegal fishing. Liu said the boat violated a fishing moratorium in Chinese waters by trawling in a forbidden zone. Liu said the boat also was using nets that were finer than allowed by Chinese law.

Taiwan's coast guard repeated its call for the release of the boat and its crew members, who were taken from waters off the Taiwanese-controlled island of Kinmen just off the Chinese coast on Tuesday night. That call was complicated by China’s refusal to communicate with Taiwan’s current government.

A spokesperson for Taiwan's coast guard, Hsieh Ching-chin, said the boat was not in Chinese waters when it was boarded by Chinese agents and steered to a port in the Chinese province of Fujian.

“First, we call on the (Chinese side) to provide an explanation, and second, to release the boat and its crew,” Hsieh said.

The Dajinman 88 was intercepted by two Chinese vessels and Taiwan dispatched three vessels to help, but one that got close to the fishing boat was blocked by three Chinese boats and told not to interfere, the Taiwanese coast guard said in an earlier statement.

Hsieh said four other Chinese boats joined in the operation, an indication of the massive expansion in recent years of China's navy, coast guard and maritime militia.

The pursuit was called off to avoid escalating the conflict, Hsieh said.

The boat has a captain and five crew members, according to Taiwan’s official Central News Agency. The crew are Taiwanese and Indonesian.

The vessel was just over 20 kilometers (12 miles) from Jinjiang in mainland China when it was boarded, Taiwanese authorities said.

China claims self-governing Taiwan is its territory and says the island must come under its control.

Fishermen from both Taiwan and China regularly sail the stretch of water near Kinmen, and tensions have risen as the number of Chinese vessels has increased.

In February, two Chinese fishermen drowned while being chased by Taiwan’s coast guard off the coast of Kinmen, prompting Beijing to step up patrols.

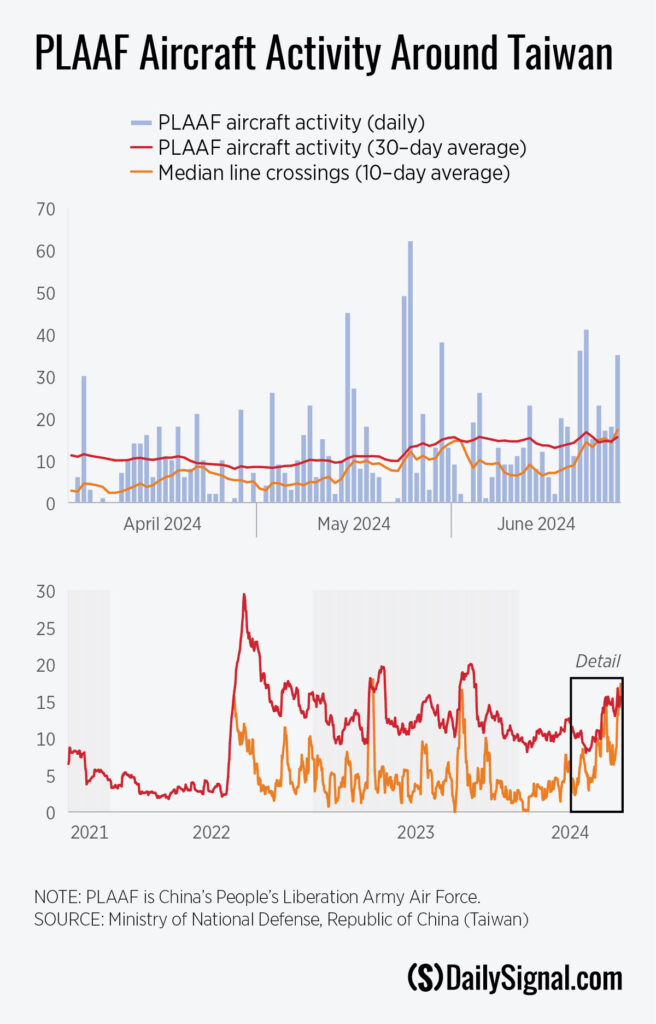

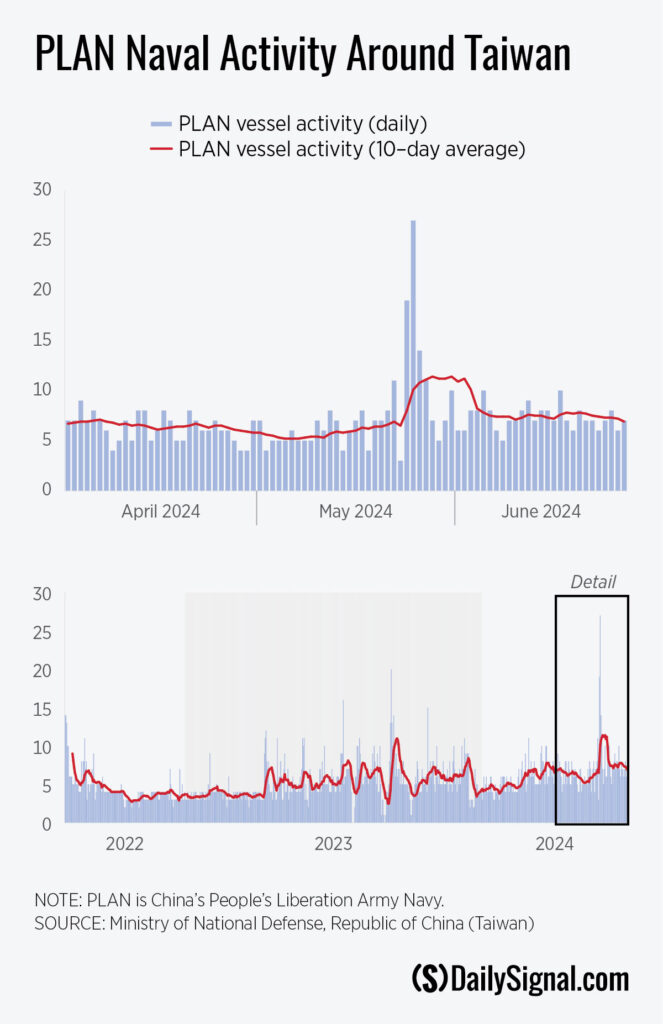

China has been increasing military actions around Taiwan's main island as well as the island groups of Kinmen and Matsu, which lie within sight of the Chinese coast. It also dispatches warplanes and navy ships daily around the island and holds military exercises, seen as rehearsals for a potential blockade or invasion.

Taiwan's Defense Ministry said 20 Chinese People's Liberation Army Air Force planes crossed the median line of the Taiwan Strait between Tuesday and Wednesday.

Last month, China passed new injunctions threatening to hunt down and potentially execute “die-hard Taiwan independence separatists.” In response, Taiwan warned its citizens to avoid visiting the mainland and the semi-autonomous Chinese cities of Hong Kong and Macao.

On Tuesday, a spokesperson for the Chinese Cabinet’s Taiwan Affairs Office said the threat only affects a hard-core minority of Taiwanese, and accused Taiwan's governing Democratic Progressive Party of “willfully misinterpreting” the action in an attempt to spread fear.

Taiwanese citizens overwhelmingly favor the island's current de facto independence status, despite military threats and diplomatic isolation imposed by Beijing.

Taiwan, a former Japanese colony, rejoined China after World War II but split away in 1949 as the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek were were defeated on the mainland by Mao Zedong’s Communists. No peace treaty has ever been signed, even as ties including direct flights between the sides have burgeoned.

Associated Press writers Dake Kang in Beijing and Didi Tang in Washington contributed to this report.

Copyright 2024 The Associated Press . All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Photos You Should See - June 2024

Join the Conversation

Tags: Associated Press , politics , world news

America 2024

Healthiest Communities

Your trusted source for in-depth analysis on the issues impacting your community’s well-being delivered right to your inbox.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Feb. 23, 2024

The Best Cartoons on Donald Trump

July 3, 2024, at 3:35 p.m.

Joe Biden Behind The Scenes

June 28, 2024

Employers Add a Solid 206K Jobs

Tim Smart July 5, 2024

Project 2025: A 2nd American Revolution?

Laura Mannweiler July 4, 2024

Biden’s Team Goes on Defense

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton July 3, 2024

Fed Voices Concern Over High Rates

Tim Smart July 3, 2024

The Supreme Court Cases That Shaped 2024

Laura Mannweiler July 3, 2024

ADP: Labor Market Is Slowing

Biden on extreme heat, hurricane beryl.

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder July 2, 2024

The global authority in superyachting

- NEWSLETTERS

- Yachts Home

- The Superyacht Directory

- Yacht Reports

- Brokerage News

- The largest yachts in the world

- The Register

- Yacht Advice

- Yacht Design

- 12m to 24m yachts

- Monaco Yacht Show

- Builder Directory

- Designer Directory

- Interior Design Directory

- Naval Architect Directory

- Yachts for sale home

- Motor yachts

- Sailing yachts

- Explorer yachts

- Classic yachts

- Sale Broker Directory

- Charter Home

- Yachts for Charter

- Charter Destinations

- Charter Broker Directory

- Destinations Home

- Mediterranean

- South Pacific

- Rest of the World

- Boat Life Home

- Owners' Experiences

- Interiors Suppliers

- Owners' Club

- Captains' Club

- BOAT Showcase

- Boat Presents

- Events Home

- World Superyacht Awards

- Superyacht Design Festival

- Design and Innovation Awards

- Young Designer of the Year Award

- Artistry and Craft Awards

- Explorer Yachts Summit

- Ocean Talks

- The Ocean Awards

- BOAT Connect

- Between the bays

- Golf Invitational

- Boat Pro Home

- Superyacht Insight

- Global Order Book

- Premium Content

- Product Features

- Testimonials

- Pricing Plan

- Tenders & Equipment

A new dawn: Inside China's rising superyacht market

China emerged as the great new hope for superyachting after the 2008 crash. One spectacular false dawn later, could it finally be taking off?

If 1421 was the zenith of China’s long yachting history, when legendary eunuch admiral Zheng He purportedly led his “treasure fleet” of hundreds of junks around the world (in the process, according to one historical account, discovering America 70 years before Columbus), 2013 could be considered the nadir. For that was when President Xi Jinping – only months into office – began a crackdown on “tigers and flies”, a euphemism for those government officials and businessmen (the genres blur in China) whose greed and corruption had begun to stir public anger.

Part of his anti-corruption crusade was an eye-watering 44 per cent import tax on luxury goods and a clampdown on lavish hospitalities and personal spending. Ostentatious symbols of wealth – fast cars, lavish banquets, his-and-hers diamond-studded Rolexes, Learjet jaunts, $20,000 gift-wrapped bottles of Rémy Martin and 50-year-old Moutai rice wine, and, of course, superyachts – became highly conspicuous and drew the wrath of the Communist Party’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection.

“We must uphold the fighting of tigers and flies at the same time, resolutely investigating law-breaking cases of leading officials and also earnestly resolving the unhealthy tendencies and corruption problems which happen all around people,” Xi said at the time. Dozens have been investigated, arrested and jailed, including top ministers – so many the Qincheng maximum security prison in Beijing for disgraced senior Communist Party officials ran out of cells last year, according to credible reports. Orders for status-symbol trappings dropped off a cliff; Western luxury retailers and manufacturers saw exports nosedive.

The yacht market was especially devastated. It’s far harder to hide a superyacht than a diamond ring or a Porsche, after all. Prior to the crackdown, China’s boating sector had been inching its way towards some kind of momentum after its once illustrious sailing heritage, having been all but erased along with much of the country’s four millennia of history during Chairman Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, was resurrected for the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Then the financial crisis struck the West, and China, with its seemingly armour-plated economy and near-double-digit growth, emerged as the great Eastern hope for leading yacht brands. Into the Chinese market sailed an international fleet of brokers and builders. The 14,500-kilometre coastline, stretching from the Bohai Gulf in the chilly north to the Gulf of Tonkin in the tropical south, was eyed as a prime playground for China’s new billionaire class, which grew to 338 individuals in 2017, according to data company Wealth-X. Estimates put the number of millionaires in the country at more than 1.5 million. China was about to go boating again.

Exhibitions were hastily organised, rendezvous booked and property developers broke ground on scores of prestige marinas, charging top-dollar membership and mooring fees, many starting at ¥1 million (£110,000) a year. Local boatyards followed, laying keels of copied foreign and home-grown designs, some in joint ventures with overseas shipyards, many without.

The image-conscious Chinese super-rich responded in kind and started buying foreign-branded trophy boats at up to three times the market price, and moored them in the expensive marinas. Cost was not an issue. What mattered was so-called “face” or mianzi: the projection, and protection, of one’s reputation and social standing. In the West we call it ego.

A 2012 report by the China Cruise & Yacht Industry Association found that there were 3,000 yachts of all sizes in China, and estimated that this figure would rise to 100,000 by 2020, in a market worth €10 billion. The international boating industry was washed along by this giddy, irrational wave of hyperbole. Across the board, orders for smaller superyachts went from zero – zoom! – skywards.

Local yards benefited. After years of being ignored by the domestic market, in 2010 Chinese yard Heysea received eight orders for its 82 model before it had even finished the mould. A year after the financial crash in the West, meanwhile, China recorded sales of ¥4.15 billion (£450 million), according to local media reports. “After 2008, the yacht market took off because the West’s financial crisis had negligible impact in China,” says Sunseeker Asia’s Gordon Hui from his office in Hong Kong. Jona Kan, from Australian yard SilverYachts , adds that demand suddenly grew for superyacht dayboats on which Chinese businesspeople could entertain clients.

But Icarus had flown too close to the sun. Within a couple of years, the world’s financial woes started to penetrate China’s economic model. Jobs were slashed and inflation was on the rise. Yet for the wealthy Communist Party cadres and their tycoon chums, it was business as usual. The restive masses looked expectantly – and threateningly – to Beijing to bring such conspicuous consumption to heel. President Xi responded with a dragnet that claimed scores of high-profile scalps, sending the message loud and clear: in-your-face luxury would no longer be tolerated.

Brokers’ phones stopped ringing, builders’ order books took a hit and showrooms became wastelands. All of those contacted by Boat International for this article echoed almost verbatim the sentiment expressed by Sunseeker’s Hui: “After more than three years of the anti-graft policy, the Chinese boating market has come to a halt, with a 95 per cent drop-off in sales. It has been all but dead since 2015.”

Sunseeker , bought in 2013 by China’s fourth-richest man, Wang Jianlin, has closed two of its three dealerships in mainland China. At one point, China accounted for 15 per cent of Sunseeker’s global sales. “Now it’s less than five per cent,” says Hui. Several Chinese yacht builders have gone bankrupt as hefty value added tax and duties on imported parts such as engines rendered operations unviable. Marinas have battened down the hatches, slashing their prices by half to avoid the fate of Xiangshan Yacht Club in Fujian province; billed as Asia’s largest marina when it opened, it went bust in 2014.

Yet to solely blame the anti-corruption drive and the global financial crash for China’s slumbering boating market is misguided. Prior to Xi’s clean-up, there had been attempts to build a culture of private boating after the former leader Deng Xiaoping launched economic reforms in 1981. But those attempts failed, says Hong Kong-based yacht broker Mike Simpson, of Simpson Marine, one of the region’s biggest boat dealers. Simpson agreed the import tax on foreign boats has had a near fatal impact, but he says there were already major hurdles to developing the fledgling market. “We have to remember China is relatively new to boating,” says Simpson, who set up his company in Hong Kong in 1983. “It’s been developing in fits and starts. An obvious curb on its development has been the import ban on second-hand boats, which was there before the luxury goods tax.”

He adds: “The last two to three years have been pretty desperate. I don’t think anyone has made money. Everyone’s been spending money just to stay in business in China over the past few years.”

The lack of a boating culture is also commonly cited as one reason that’s holding back the Chinese market. In the West, yachting is all about relaxing fun in the sun, a weekend jaunt from one marina to a secluded cove or island, or for sailing boat owners, the thrill of stealing an opponent’s wind during a regatta. In China, owning a yacht has been all about the optics, or “face”, and viewed by the public as the exclusive preserve of the ultra-rich. But even among this demographic, interest is limited. According to Wealth-X, just two per cent of all Chinese UHNW individuals own or even have an interest in yachting, compared to 6.7 per cent globally.

“The perception among the Chinese is that boating is for the very wealthy,” says Rocky Wang, chief representative of Burgess in China. “Many Chinese have yet to grasp what boating is all about. Boating culture remains in its very early stages. Yachting is very new to them. Those Chinese who think about buying yachts continue to do so with mainly a business objective in mind. Buyers are business owners, investors and entrepreneurs, who use the yachts as dayboats to entertain, rarely overnighting on board.”

Of the 200 yachts in the southern boom city of Shenzhen, where Deng Xiaoping launched China’s opening up and reforms half a century ago, about 70 per cent never leave the yacht club. Instead, they serve as venues to host wealthy clients and government officials; one pontoon legend has it that some boats were bought without engines because their owners never entertained the idea of going to sea.

In China, building a $30 million marina with a plush clubhouse and spa is the easy part. Not so easy is attracting the essential supplemental services: repair yards and chandlers, navigation aids, charts, a coastguard service willing to assist the stranded sailor, sail training schools and so on. A lack of trained Chinese crew is also a major problem. In China there are an estimated 60,000 sailors, mostly of school age, attending small sailing centres and learning in dinghies. Crews experienced enough to handle a 60-metre-plus seagoing vessel are a rarity. “Chinese yacht owners must, therefore, import foreign crews with the expertise to maintain and sail boats, and this comes with visa application headaches,” says Simpson.

Then there is the maddening red tape. China guards its coastal waters like a hawk; try to sail a nautical mile off Qingdao beach or a cable or two up the coast from Sanya and you’ll have patrol boats stuffed to the gunnels with uniformed boarding parties bearing down on you demanding papers; a day’s sail is treated like an invasion or a desperate escape with state secrets.

“It’s true,” concedes William Ward, CEO of the biannual round-the-world Clipper Race, which during its last edition stopped twice in China, in Sanya in the south and Qingdao in the north. “The government protects the inshore waters as it would an inland military installation. It’s overbearing, there’s too much red tape, and you just don’t need that. You need to be able just to hop on your boat, slip your lines and head out for some safe fun and relaxation, just as we can in the UK, or in the Med and everywhere else,” he says.

Then there’s China’s geography. Part of the appeal of cruising is exploring idyllic archipelagos or mooring off a chic seaside town. Only in the south, around the island of Hainan, can you find good cruising with accommodating marinas. Even then, as Ward recently experienced, just heading out for a day’s jaunt demands official clearance to slip your lines, which may or may not be granted.

Little wonder those Chinese who own a superyacht, or are still in the market for one, seek to moor their pride and joy outside China, in places like Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Australia, while the ultra-wealthy look to the US and the Med.

Not for the first time, there might be signs of a new dawn appearing for China’s boating market. In April, the Pride Mega Yachts shipyard in Yantai, China, rolled out the spec-built 88.5 metre superyacht Illusion Plus , which later appeared at the Monaco Yacht Show. She’s now listed for sale , asking $145 million. If she sells well, it will be a sign of faith in Chinese yacht building.

Chinese conglomerates are once more seeking to own international superyacht brands. China Zhongwang, the world’s second-largest producer of industrial aluminium extrusion products, recently acquired a controlling interest in Australia’s SilverYachts, which builds high-speed, fuel-efficient superyachts from high-grade aluminium. The yard’s commercial director, Jona Kan, says the boatbuilder will soon announce the acquisition of a shipyard in the Pearl River Delta.

Sunbird, a Chinese conglomerate with five shipyards including a large commercial facility, added IAG Yachts to its varied portfolio in 2015, and turned out to solid reviews the 42.7 metre King Baby , the largest fibreglass motor yacht ever produced in China.

Heysea Yachts, founded in 2007 and one of China’s largest yacht builders, was a new entry in the Boat International Global Order Book’s Top 20 builders in 2018 and holds its place in this year’s report. Chairman Allen Leng says the company is seeing more interest from domestic buyers because it is adapting to local tastes, by placing the galley down below and including more living and entertainment space, with fewer cabins. “There is an increased number of Chinese clients who better understand the culture of boating and the lifestyle it offers; that boat ownership is more than having a floating platform for business and to boost one’s image,” says Leng. “More Chinese customers are accepting that China-made yachts offer quality and the same after-sales service as foreign brands. We’re also noticing a demand for smaller yachts, which shows the link between sailing and sport and leisure, and that boating is not just a rich person’s pursuit.”

Horizon Yachts says its product range, including new projects such as the FD series, are proving popular with Chinese clients, who are becoming more sophisticated in their tastes. “For example, a buyer in Shanghai or in Sanya will moor their yacht in a yacht club and let the club manage it. In the past five years, we have delivered a 120ft [36.5 metre] superyacht and 145ft [44.2 metre] superyacht, both to clients in Shanghai,” says Horizon Yachts’ chief marketing officer, Lily Li.

Simpson Marine’s Mike Simpson estimates that around 50 per cent of yachts being bought in China are now locally built. “The standard is improving,” he says. “Sometimes you have to do a double-take when you see yachts coming: you think it’s a well-known foreign brand. Then you look again and it’s actually a locally made boat.”

Sunseeker’s Hui also expresses modest optimism. “I think the market overall is getting better, albeit slowly,” he concedes. “I can say 70 per cent of our 2015 to 2018 customers are mainland Chinese with overseas-listed companies. But their boats are all outside China.”

Grassroots sailing and crew training recently received a much-needed boost. In April, the UK’s then deputy ambassador to China, Martyn Roper, and the president of the Chinese Yachting Association, Qu Chun, signed deals to open three training centres to bring Chinese seamanship up to British standards. The centres will offer the UK’s Royal Yachting Association courses. In the UK, seven per cent of the population goes boating. If the same percentage could be replicated in China, that would mean 80 million people taking confidently to the water.

Simpson says a new initiative called the Greater Bay Area development scheme is seeking to unify nine mainland coastal cities to allow yachts licensed in Hong Kong and Macau to cruise in the good southern cruising areas around Hainan without paying a hefty tax. And there is quiet and determined diplomacy afoot calling for Beijing to relax and standardise coastal regulations. Ward, the Clipper Race CEO, says he has been speaking to officials at city and provincial levels who understand the benefits of rationalising China’s sailing industry and its associated tourist trade. “I have spoken with many officials and they get this point. They understand the [stifling red tape] situation, and they’re passing these concerns up to Beijing, that leisure sailing is a different culture and is good for local and regional business,” he says.

There are signs of a cultural shift, too. At the 2018 Shanghai Boat Show , many of the exhibitors were proposing something different – more accessible yachting, with small fishing boats and cruisers standing cheek by jowl with the bigger craft, says Delphine Lignières, co-founder of the Hainan Rendez-Vous. “Contrary to myth, many Chinese enjoy watersports, including sailing and fishing. What I have seen now is more and more people boating on inland freshwater lakes in smaller-sized boats.

“That’s where I see the market developing this time, with smaller recreational boats being bought for use on lakes, rivers and estuaries. This will help establish a boating culture, and over time, the boats will again get bigger and bigger. And not in such a conspicuous way.”

More stories

Most recent, from our partners, sponsored listings.

- Share story on Facebook

- Share story on Twitter

- Share story via email

- Share story via SMS

- Share story on LinkedIn

- Submit story to Reddit

- Post story on Pinterest

- Share story on Google+

- Post story on WhatsApp

- Copy story information for sharing Unmasking China's invisible fleet: For years, no one knew why dozens of battered wooden "ghost boats" were routinely washing ashore along the coast of Japan. Now, an investigation by the journalism organization The Outlaw Ocean Project has revealed that China is sending an armada of industrial boats to illegally fish in North Korean waters, displacing smaller North Korean boats.

Unmasking China's invisible fleet

Satellite data exposing illegal fishing in North Korean waters reveals breadth of China's ambitions at sea

By Ian Urbina of The Outlaw Ocean Project, for CBC News

July 23, 2020

This story is a part of a documentary series produced in collaboration with NBC News by The Outlaw Ocean Project , a non-profit journalism organization based in Washington, D.C., that focuses on human rights, labour and environmental crimes at sea.

For years, no one knew why dozens of battered wooden "ghost boats" were routinely washing ashore along the coast of Japan, often with the bodies of starved North Korean fishermen reduced to skeletons.

An investigation by the journalism organization The Outlaw Ocean Project based on satellite data collected over the last two years has revealed, however, what marine researchers now say is the most likely explanation: China is sending an armada of industrial boats to illegally fish in North Korean waters, displacing smaller North Korean boats, forcing them farther out to rougher seas, and spearheading a decline in once-abundant squid stocks of more than 70 per cent.

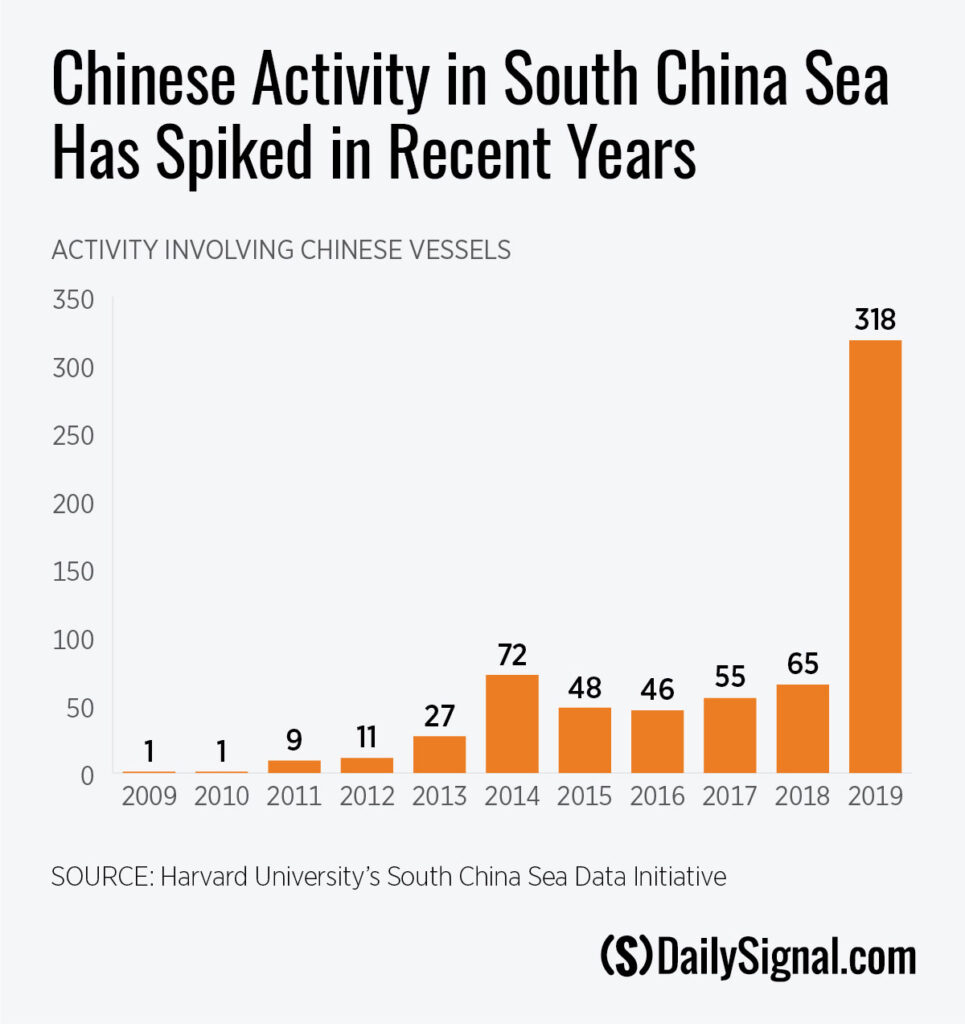

The Chinese vessels — close to 800 last year — appear to be in violation of UN sanctions that forbid foreign fishing in North Korean waters in the Sea of Japan, also known as the East Sea. The sanctions, imposed in 2017 in response to the country's nuclear tests, were intended to punish North Korea by not allowing it to sell fishing rights in exchange for valuable foreign currency. (Canada is one of the countries helping to enforce those sanctions.)

The number of ships newly revealed in the investigation comprises roughly a third the size of the entire Chinese distant-water fishing fleet. The public and commercial satellite data was analyzed by Outlaw Ocean, Global Fishing Watch and researchers and academics from the U.S., South Korea and Japan. It was also peer-reviewed and published in the academic journal Science Advances.

"This is the largest known case of illegal fishing perpetrated by a single industrial fleet operating in another nation's waters," said Jaeyoon Park, a data scientist from Global Fishing Watch , which tracks commercial fishing vessels around the world.

Presented with the findings, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that, "China has consistently and conscientiously enforced the resolutions of the Security Council relating to North Korea." The ministry said China has "consistently punished" illegal fishing.

It is unclear whether the North Korean government has authorized the Chinese ships. However, when South Korean Coast Guard authorities have boarded and inspected some of the ships as they traversed South Korean waters on their way to North Korean fishing grounds, the Chinese captains have presented fishing permits signed by North Korean authorities.

An elusive but expanding fleet

In March, two countries anonymously complained in a report to the United Nations about China's violations of the sanctions and provided satellite imagery of Chinese ships fishing in North Korean waters and testimony from Chinese fishing crew who said they had alerted their government of their plans to fish in North Korean waters.

Chinese officials dismissed this report, claiming the allegations were unfounded and involved scant few boats.

The recent revelations raise thorny questions about the consequences of China's ever-expanding role at sea and the lack of governance of the world's oceans.

Estimates of the total size of China's global fishing fleet vary widely. By some calculations, China has anywhere from 200,000 to 800,000 fishing boats, accounting for nearly half of the world's fishing activity. The Chinese government says its distant-water fishing fleet, or those vessels that travel far from China's coast, is roughly 2,600 vessels, but other research, such as this study by the U.K. think-tank ODI, puts the number closer to 17,000, with many of these ships operating undetected, in part by turning off the transponders that allow satellites to track them.

By comparison, the United States distant-water fishing fleet has fewer than 300 vessels.

China is not only the world's biggest seafood exporter. The country's population also accounts for more than a third of all fish consumption worldwide. Having depleted the seas close to home, the Chinese fishing fleet has been sailing farther afield in recent years to exploit the waters of other countries, including those in West Africa and Latin America, where enforcement tends to be weaker as local governments lack resources or inclination to police their waters. Most Chinese distant-water ships are so large that they scoop up as many fish in one week as local boats from Senegal or Mexico might catch in a year.

Many of the Chinese ships combing Latin American waters target forage fish, which is ground into fishmeal, a protein-rich pelletized supplement fed to aquaculture fish. The Chinese fleet has also focused on shrimp and the now endangered totoaba fish, which is much prized in Asia for the alleged medicinal properties of its bladder and can sell for between $1,400 and $4,000 per fish.

Nowhere at sea is China more dominant than in squid fishing, as the country's fleet accounts for 50 to 70 per cent of the squid caught in international waters, effectively controlling the global supply of the popular seafood. Half of the squid pulled from the high seas by Chinese fishermen is exported to Europe, north Asia and the U.S.

To catch squid, the Chinese typically use trawling nets stretched between two vessels, a practice criticized by marine conservationists because it results in a lot of fish inadvertently and wastefully killed. Critics also accuse China of keeping high-quality squid for domestic consumption, exporting lower-quality products at higher prices, overwhelming vessels from other countries in major squid breeding grounds, and influencing international negotiations about conservation and distribution of global squid resources for its own interest.

Subsidizing squid

China's global fishing fleet did not grow into a modern behemoth on its own. The government has robustly subsidized the industry, spending billions of yuan annually. Chinese boats can travel so far partly because of a tenfold increase in diesel fuel subsidies between 2006 and 2011, after which Beijing stopped releasing statistics, according to a Greenpeace study.

For over a decade, the Chinese government has helped pay to construct bigger, more advanced steel-hulled trawlers, even sending medical ships to fishing grounds to enable the fleet to stay at sea longer. The Chinese government supports the squid fleet in particular by providing it with an informational forecast of where to find the most lucrative squid stocks, using data gleaned from satellites and research vessels.

On its own, distant-water squid fishing is a money-losing business, according to research by Enric Sala, founder and leader of the U.S. National Geographic Society's Pristine Seas project. The sale price of squid typically does not come close to covering the cost of the fuel required to catch the fish, Sala found.

Still, China is hardly the worst offender when it comes to such subsidies, which ocean conservationists say, through over-capacity and illegal fishing, are a major reason that the oceans are rapidly running out of fish. The countries that provide the largest subsidies to their high-seas fishing fleets are Japan (20 per cent of the global subsidies) and Spain (14 per cent), followed by China, South Korea, and the United States, according to Sala's research.

More recently, the Chinese government has stopped calling for an expansion of its distant-water fishing fleet and released a five-year plan that restricts the total number of offshore fishing vessels to under 3,000 by 2021.

Other attempts to rein in this fishing fleet, however, have been slow. Though China has modernized the industry's fishing gear, ship engines, radar and offshore cold storage, the government's efforts at regulation have not kept pace. Imposing reforms and policing them is difficult partly because laws are lax, much of the workforce on vessels is illiterate, many ships are unlicensed and lack the unique names or identifying numbers needed for tracking, and the country's fishery research institutions often refuse to standardize or share information domestically or abroad.

WATCH | Follow Ian Urbina of The Outlaw Ocean Project as he and Global Fishing Watch track Chinese squid ships in the Sea of Japan, or East Sea:

Still, more than seafood is at stake in the present size and ambition of China's fishing fleet. The country's commercial fishermen often serve as de-facto paramilitary personnel whose activities the Chinese government can use to further its geopolitical aims. This ostensibly private armada helps assert territorial domination, pushing back fishermen or governments that challenge China's sovereignty claims, which encompass nearly all of the South China Sea.

"What China is doing is putting both hands behind its back and using its big belly to push you out, to dare you to hit first," Huang Jing, the director of the Center on Asia and Globalization at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore.

Chinese fishing boats are notoriously aggressive and often shadowed, even on the high seas or in other countries' national waters, by armed Chinese Coast Guard ships.

Swarming the zone

With competing historical, territorial and even moral claims from China, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan and Indonesia, the South China Sea is among the most hotly contested regions in the world. Aside from fishing rights, the interests in these waters stem from a tangled morass of national pride, lucrative subsea oil and gas deposits and a political desire for control over a region through which a third of the world's maritime trade flows.

In the South China Sea, the Spratly Islands have attracted most attention as the Chinese government has built artificial islands on reefs and shoals in these waters, militarizing them with aircraft strips, harbours and radar facilities. Chinese fishing boats bolster the effort by swarming the zone, intimidating potential competitors, as they did in 2018, suddenly dispatching more than 90 fishing ships to drop anchor within several miles of Philippines-held Thitu Island, immediately after Manila began modest upgrades on the island's infrastructure.

And yet, clashes over fishing grounds involving the Chinese are not limited to the South China Sea. Japan and China are at odds over the Senkaku Islands, known in Chinese as the Diaoyu, or "fishing" islands, and the Argentine Coast Guard has opened fire on Chinese fishing vessels entering its waters.

From North Korea to Mexico to Indonesia and South America, incursions by Chinese fishing ships are becoming more frequent, brazen and aggressive. It hardly takes a great feat of imagination to picture how a seemingly civilian clash could rapidly escalate into a bigger military conflict.

About the author and the project

Ian Urbina is a former investigative reporter for the New York Times whose work has also appeared in The Atlantic, The New Yorker and elsewhere . He is the director of The Outlaw Ocean Project , a non-profit journalism organization based in Washington, D.C., that focuses on reporting about environmental and human rights crimes at sea. Some of his investigative work on this subject was published last year in his book The Outlaw Ocean: Journeys Across the Last Untamed Frontier . Follow him at @ian_urbina on Instagram and Twitter or @ianurbinareporter on Facebook .

Related stories

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Taiwan says China’s coast guard has detained a Taiwanese fishing vessel and demands its release

FILE - A fisherman leaps to his boat docked in harbor in Toucheng, north eastern Taiwan, Aug. 21, 2013. Taiwan said the Chinese coast guard boarded a Taiwanese fishing boat Tuesday, July 2, 2024, before steering it to a port in mainland China, and demanded that Beijing release the vessel. (AP Photo/Wally Santana, File)

- Copy Link copied

TAIPEI, Taiwan (AP) — Taiwan said the Chinese coast guard boarded a Taiwanese fishing boat Tuesday before steering it to a port in mainland China, and demanded that Beijing release the vessel.

The Tachinman 88 was intercepted by two Chinese vessels Tuesday evening near the Kinmen archipelago, which lies a short distance off China’s coast but is controlled by Taiwan, Taiwanese maritime authorities said in a statement.

Taiwan dispatched three vessels to rescue the Tachinman 88, but the one that got close to the fishing boat were blocked by three Chinese boats and told not to interfere, the statement said. The pursuit was called off to avoid escalating the conflict after Taiwan’s maritime authorities detected that four more Chinese vessels were moving closer, the statement added.

“The Coast Guard calls on the mainland to refrain from engaging in political manipulation and harming cross-strait relations, and to release the Tachinman ship and crew as soon as possible,” the statement read.

The boat had six crew onboard, including the captain and five migrant workers, according to Taiwan’s official Central News Agency. The vessel was just over 20 kilometers (12 miles) away from Jinjiang in mainland China when it was boarded, Taiwanese authorities said.

China claims self-governing Taiwan as its territory and says the island must come under its control. The Chinese military regularly sends warplanes and ships toward the island and staged a large exercise with dozens of aircraft and vessels in May.

Fishermen from both Taiwan and China regularly sail the stretch of water near the Kinmen archipelago, which has seen a rise in tensions as the number of Chinese vessels — including sand dredgers and fishing boats — have notably increased in the area.

In February, two Chinese fishermen were drowned while being chased by Taiwan’s Coast Guard off the coast of Kinmen, prompting Beijing to step up patrols in the waters.

By SuperyachtNews 11 May 2021

China and Hong Kong: superyacht market dynamics

As china’s billionaire population hits record numbers, the industry is still trying to grow this budding market….

There are few geographical markets that present the superyacht industry with the same opportunity for growth as the Chinese market. Still at a relatively early stage of yachting development, in terms of domestic infrastructure and ownership, China certainly has a large, and growing, pool of potential superyacht buyers. Knight Frank’s 2021 edition of The Wealth Report recently set out its list of top-10 risers – the 10 countries that saw the biggest increase in their UHNWI population in 2020 – revealing that China saw the largest increase, at 16 per cent.

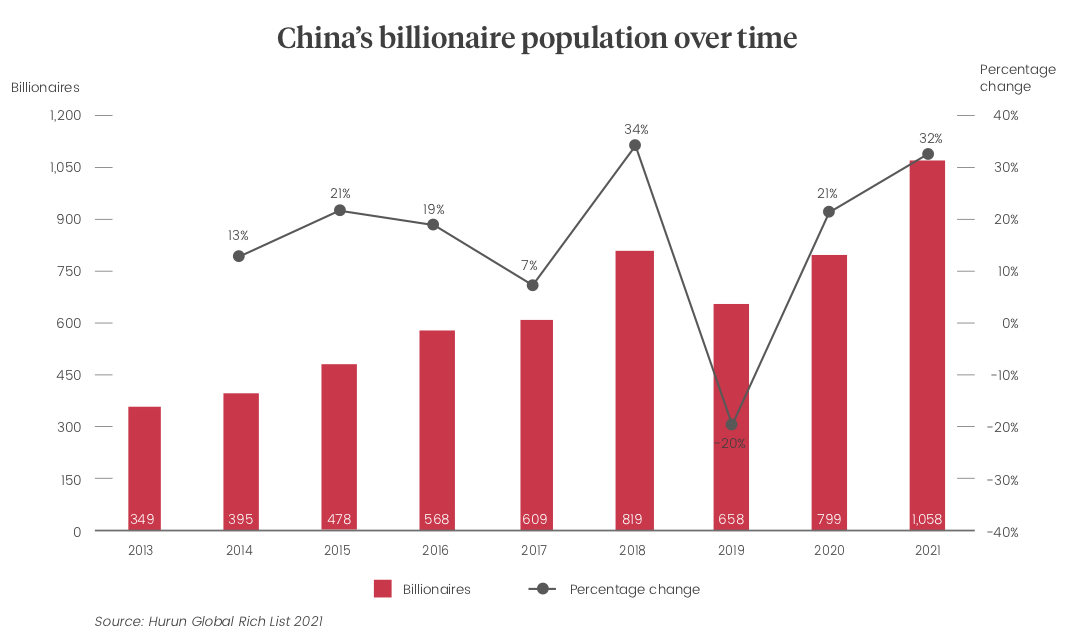

Furthermore, according to Hurun Report’s Hurun Global Rich List 2021 , China has outpaced the United States to become the first country in the world with more than 1,000 billionaires. The publication reveals that, at the beginning of 2021, China had 1,058 billionaires with their wealth denominated in US dollars. “Despite the trade war with the US, China adds 259 billionaires and becomes the first country with more than 1,000 known billionaires, surpassing other countries including the US, India and Germany,” the report says.

In light of the region’s growing billionaire population, the recently-published The Pacific Superyacht Report explores the current dynamics at play in the Chinese superyacht market from a buyer perspective, as well as the potential that China and Hong Kong present to the superyacht industry.

“There is definitely an upward trend in the superyacht market in China, as the wealth of the mainland Chinese increases,” says Joe Yuen, of Lodestone Yachts. “The Chinese tend to purchase new superyachts from production yacht dealers, but now you see more and more Chinese buying semi-custom or full-custom superyachts through professional yacht brokers. The production yacht dealers have done well with their marketing in the region, and you are also beginning to see larger semi-custom superyachts cruising in the harbours.”

When talking about the Chinese superyacht market, it is important to distinguish between the Hong Kong market and mainland China market. As Rock Wang, Feadship’s Asia representative, explains, “Hong Kong is already a very mature yachting market, so there isn’t much potential for growth. While mainland China is already very active, it will be growing rapidly in the next 10 years.”

The reasons for these two markets being at two very different stages of yachting development are well documented. While Hong Kong may have a longer history of a yachting culture than mainland China, the most obvious barrier to the growth of the domestic Chinese market is its weighty import duties on foreign yachts, compared to tax-free Hong Kong.

“The matter of taxation has been a major limiting factor,” says Mike Simpson, managing director of Simpson Marine. “There is a very high import tax on yachts, it has been 43.65 per cent, but that has recently been reduced to 38.1 per cent on motoryachts and 35.6 per cent on sailing yachts over 8m [at the time of writing]. The tax has been a big deterrent for a lot of people – when you are spending a large amount of money to buy a yacht, no one is very happy about spending nearly 50 per cent more for the privilege of bringing it into, and flagging it in, China.”

For Simpson, however, the biggest barrier to the growth of the domestic market is the perception that superyachts in China are going to attract a lot of attention. “Currently there are only about 30 yachts over 30m in southern China altogether (excluding Hong Kong), so any new yacht is going to stand out, and this is not always very welcome. Normally, the wealthy try and keep a low profile,” he continues. “There is plenty of wealth in China, but there is a fear of attracting attention by any obvious displays of wealth.”

“There is plenty of wealth in China, but there is a fear of attracting attention by any obvious displays of wealth...”

In both the Hong Kong and mainland China markets, buyer habits differ depending on the size sector they are buying into, and whether they are buying for domestic or overseas use. According to Wang, because the majority of marinas in Hong Kong offer berthing up to 35m, both the 30-35m new-build and brokerage markets in Hong Kong are very active, with most clients keeping their boats in Hong Kong and using them as day or weekend boats for local cruising. For the larger size sectors, however, clients tend to enjoy their boats overseas due to the berthing limitations of Hong Kong’s marinas.

Wang observes further intricacies in the 35m-plus sector depending on size range, with Hong Kong clients generally preferring to buy new over second-hand. “Buying a yacht is more expensive in the 35-60m size range, so clients spending this much money tend to want something new,” he explains. “About 60-70 per cent of these clients will choose a new build. Most clients also don’t want to wait too long for their yacht, but thankfully many shipyards offer production or semi-custom models in this size range, which shortens build time.”

According to Wang, this preference for ‘something new’ augments even further in the 60m-plus market. “The vast majority of clients want a new-build when buying a yacht over 60m,” he adds. “Every yacht of this size has a very specific personality and, because of this, many of the clients I have worked with feel that a second-hand yacht of this size does not and would not belong to them.”

In terms of the market in mainland China, there are other dynamics at play. With government restrictions on the import of second-hand yachts older than one year, as well as a lack of brokerage agencies and surveyors to advise clients on second-hand purchases, there is virtually no second-hand brokerage activity within China, even in the 30-35m sector, where berthing is easier.

However, the mainland Chinese ownership in the 35m-plus market is similar to that of Hong Kong. “Except that the mainland Chinese prefer to buy new builds even more than Hong Kong clients,” he says. “It is the Chinese mentality; if they are spending 20-30 million euros, they want something new.”

In terms of market potential for the superyacht industry, the Chinese market is huge in the same way that the country’s population is huge and, in light of the country’s rapidly growing population of UHNWIs, Wang is very optimistic about the future potential of the market in mainland China. He puts it simply: “It’s human nature. When you have a lot of money, you want to enjoy life and yachting is one of the best ways to enjoy life.”

“From the crew to the brokers and designers, every sector of this industry is lacking Chinese professionals...”

Despite this optimism, Wang believes that there are certain changes that could be made in order to help stimulate growth. One barrier is the scarcity of Chinese representation in the industry. “From the crew to the brokers and designers, every sector of this industry is lacking Chinese professionals,” he says. “As an international community, we should look to find Chinese talent. If there were just 15 to 20 Chinese brokers, the market would change. Shipyards also need to have marketing material in Chinese because the majority of Chinese clients feel more comfortable reading Chinese than English. It is something very basic that the industry can do today that will have a significant impact in the future.”

Simpson agrees that a lack of qualified local crew is certainly a limiting factor to the growth of the Chinese market. “Owners accept that they will have to hire qualified foreign crew for now, but many Chinese owners don’t speak English and they would rather have at least some crewmembers who can communicate with them in their own language,” he says, adding that optimism lies in the MCA-approved Galileo Maritime Academy, Thailand. The Academy offers training courses to the Asia region, which will help to get more local crew trained up and qualified to work on superyachts in the future.

More infrastructure to attract visiting yachts would also help to give the superyacht industry more visibility in China, and possibly attract the attention of qualified buyers. “When there are more marinas and professional crew, this will help increase the popularity of superyachts,” concludes Yuen. “The Chinese government is also promoting various types of tourism, including yacht tourism, in the Free Trade Zone of Hainan Island and The Greater Bay Area. I hope this will bring more charter yachts to the Far East.”

This article appears in full in the recently-published The Pacific Superyacht Report . For complimentary digital access to the magazine, please click here.

Profile links

Simpson Marine Limited

Join the discussion

To post comments please Sign in or Register

When commenting please follow our house rules

Click here to become part of The Superyacht Group community, and join us in our mission to make this industry accessible to all, and prosperous for the long-term. We are offering access to the superyacht industry’s most comprehensive and longstanding archive of business-critical information, as well as a comprehensive, real-time superyacht fleet database, for just £10 per month, because we are One Industry with One Mission. Sign up here .

Related news

The Pacific Superyacht Report

The issue amalgamates the most pertinent themes from such an expansive and diverse region

3 years ago

Sign up to the SuperyachtNews Bulletin

Receive unrivalled market intelligence, weekly headlines and the most relevant and insightful journalism directly to your inbox.

Sign up to the SuperyachtNews Bulletin

The superyachtnews app.

Follow us on

Media Pack Request

Please select exactly what you would like to receive from us by ticking the boxes below:

SuperyachtNews.com

Register to comment

- Asia Briefing

- China Briefing

- ASEAN Briefing

- India Briefing

- Vietnam Briefing

- Silk Road Briefing

- Russia Briefing

- Middle East Briefing

China’s Yacht Market: Opportunities and Challenges for Foreign Players (updated)

China appears well-positioned to become a prominent yacht market, given its 14,484km-long coastline and a class of millionaires expected to cross the 20 million mark by the mid-2020s. Despite this, however, sales have been disappointing i n the last 3-5 years due to high import tax and the inability of manufacturers to respond to Chinese client demands. In this article, we provide a general overview of China’s yacht market and discuss the differences in business outlook according to key stakeholders, ranging from optimism over market growth potential or concerns about limited domestic prospects . We also discuss the recent entry of Chinese capital in the industry and how Chinese companies are manufacturing for non-China markets. Finally, we look at opportunities for foreign investors in China’s boat market, including prospects for small and mid-cap companies, and showcase the success cases of Italian companies.

UPDATE: O n August 18, 2 0 22, the Ministry Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), together with the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Finance (MOF), the Ministry of Transport (MOT) , and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (MCT), jointly released on the Guidelines on Accelerating the Development of Cruise and Yacht Equipment and the Industry (Guidelines) , clarifying China’s roadmap for the development of the yacht industry through 2025. More details are provided below .

While North America and Europe remain in the lead as the world’s largest yacht consumers, the Asia-Pacific region has rapidly become one of the fastest-growing yacht markets. The yacht market in Asia has been skyrocketing post-pandemic, with increased purchases and a growing interest in sailing – sparking what industry experts define as a ‘boom’. On the one hand, countries like Taiwan and China have increased their market share with new builds by locally-based shipyards. However, boat sales to the region are also on the rise.

As of 2021, Asian ownership of superyachts over 40 meters in service accounted for 5.8 percent of the global superyacht fleet. The number of Asian-owned yachts has progressively increased, from 91 at the beginning of 2016 to 109 at the start of 2021. Countries like Singapore have become active once again in the yacht sales ad brokerage market s after a slow period during the pandemic that triggered international and regional border closures.

In China, heightened living standards have led to the increasing demand for luxurious consumer goods, including in the boating industry. According to the China Transport Association’s Cruise Yacht Branch, the total number of yachts in China will increase from 38,100 to 163,510 between 2020 and 2025.

China’s yacht market: an overview

Few geographical regions offer the superyacht sector as much room for expansion as the Chinese market does. China has a vast and increasing pool of potential superyacht purchasers, although the country is still in the early stages of yachting growth in terms of domestic infrastructure and ownership. It could still be the right time for such a high-potential market to flourish due to factors like the increase in the country’s per capita purchasing power and that of its ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) population.

A 2021 wealth report revealed the 10 countries with the highest increase in their UHNW population in 2020 – the so-called ‘top 10 riders’ – with China leading the group at 16 percent growth. Furthermore, in 2021, China surpassed the United States to become the world’s first country with over 1,000 billionaires. The research highlighted that, despite the trade war and the pandemic, China was able to add 259 billionaires to its list, surpassing other nations like the US, India, and Germany.

With a large number of prospective consumers, China’s relatively new market is even more attractive for foreign businesses. New yacht manufacturers, brand sales agents, yacht customers, private clubs, and exhibits have sprung up throughout the country in recent decades. Meanwhile, China’s boat manufacturing keeps rising steadily, from 29,100 units produced in 2011 to 48,300 units in 2015. China’s yacht industry is estimated to reach US$15.1 billion in 2027, accounting for 17.8 percent of the worldwide market and growing at a CAGR of 3.9 percent between 2020 and 2027.

Less stringent regulations demonstrating the government’s commitment to the sector

Many positive government efforts linked to the yachting industry and maritime activities, in general, have lately been enacted, and China is seeing a trend of loosening regulations. At the outset of this decade, two regulatory bodies – the Ministry of Transport and the Maritime Safety Administration (MSA) – announced new, more liberalized criteria and standards for yacht registration and overseas-yacht entry/exit procedures.

More limitations on boat ownership have been abolished in recent years, and clear maritime traffic legislation has been adopted. The increase of the navigability range, the streamlining of the examination/approval processes, and the inclusion of non-resident yacht registrations are the three most recent major amendments to the rules. These key developments show the government’s commitment to the sector’s growth.

Also, as wealthy Chinese yacht owners spend about 10 percent of the yacht’s value on maintenance, a large portion of this wealth is reinvested in the local economy. This not only is a great boost for regional GDP but is also in line with the government’s will of shifting its economy away from production to consumption. It has likely prompted Chinese officials to ease the cumbersome registration process for importing a yacht into the country, as well as the requirements for traveling between provinces. Yachts registered in Hong Kong and Macao, for example, were allowed to sail in China’s Pearl River Delta beginning 2018. The first cross-border sailing program has also increased boat orders in the Chinese Mainland by 20 percent to 30 percent.

Accordingly, The State Council Office evaluated the Guidance on Tourism Industry Acceleration and drafted a National Tourism and Entertainment Outline (2013-2020) in which measures were taken to improve the infrastructure for yacht marinas and cruise terminals, as well as encourage the growth of tourism products.

Yacht market more prosperous in certain regions than others: The case of Hainan Free Trade Zone

The yacht business in Hainan Province flourished in 2021 – the Sanya Yachting Association revealed that Sanya, China’s tropical island and premier destination for luxury tourism, hosted almost 160,000 yacht trips, up 47 percent compared to 2020. Moreover, by the end of 2021, the number of new yachts registered reached 323, surging 202 percent year on year.

This increase is partly due to the Overall Plan for the Construction of Hainan Free Trade Port (“the Masterplan”) that was released in June 2020, which stipulates that by 2025, there will be no tariffs on the island’s import of ships for transportation, tourism, and other purposes. Import tariffs, the value-added tax, and the consumption tax will all be waived for foreign exporters – which will effectively cut prices for foreign-made products.

Success stories: Italian yacht businesses in China

With 407 projects and super-yachts totalling 14,994 meters in development in 2021, Italy continues to top the annual report issued by the nautical newspaper ShowBoat International. Azimut-Benetti, Sanlorenzo, and Ferretti Group occupy the first, second, and third place, respectively.

Despite having eight well-known brands, six shipyards, and over 170 years of history, Ferretti Group is today the only rival in its business to provide a comprehensive range of yachts ranging in size from 8 to 95 meters, and it is very active in China’s yacht market. After defaulting in 2009, the company was bought in 2012 by SHIG–Weichai Group, a large Chinese machinery manufacturer that currently controls 75 percent of the Italian shipbuilder.

Following the acquisition, the company focused on growing into new markets. It made a great impression in the Asia-Pacific region in the first quarter of 2020, selling about US$73 million and negotiating two new dealership agreements for the distribution of its yachts in Malaysia, Cambodia, and Laos. The Italian shipbuilder now has offices in Hong Kong and Shanghai, as well as a fully equipped after-sales facility, to meet the needs of its customers in the region. It also inked a Memorandum of Understanding with the Sanya Central Business District (SCBD) to collaborate with the government on the development of the local industry and China’s yacht market in general.

Other than larger and well-established companies, opportunities are there for everybody. According to Giovanni Lovisetti , Senior Associate on the International Business Advisory at Dezan Shira & Associates’ Milan Liaison office , “while huge companies can approach Asian markets by themselves – such as Fincantieri, who has already established a presence in Hainan – several smaller companies are just waiting for the right stimulus to take the first step towards Asia.” This might be the right time for them to step in.

Roadblocks to the development of China’s yacht market

High import taxes on foreign boats are one of the primary hurdles to the development of China’s yacht sector. The country has a 43.65 percent tax on boats – although recently reduced to 38.1 percent for motor yachts and 35.6 percent for sailing yachts above 8 meters. Furthermore, since the beginning of the government’s Anti-Corruption Campaign in 2012, potential customers have been reluctant to flaunt their wealth, preferring to keep a low profile and avoid public scrutiny.

Another considerable barrier to Chinese high-income individuals buying private boats in the Mainland, is the lack of well-equipped marinas, ship repair yards, spare parts suppliers, and all other necessary (and expensive) infrastructure for yacht upkeep and mooring.

Lastly, in 2015, China strengthened its regulations for yachts travelling in its national waters, restricting the number of passengers onboard to a maximum of 12 people – which made it impossible to arrange large parties and gatherings on board since the crew alone counts six members. Furthermore, China’s southern shoreline land is a particularly difficult marine zone due to ongoing territorial conflicts with neighboring states.

As a result, several of the world’s most prestigious shipbuilders, like Sunseeker and Ferretti Group, have shuttered their showrooms in Mainland China or eliminated the country from their core target markets, despite their Chinese ownership. Regardless, those companies continue to sell boats to Chinese customers for delivery outside of the Mainland.

Understanding the Chinese market and its cultural context

Four purposes for boats are sailing, sports, leisure, and entertainment. For wealthy Chinese buyers, the latter would be the most common option. Given that the high-income Chinese population has little interest in sunbathing, the primary aim of these luxury boats in the contemporary setting would be to serve as a business frontier for hosting meetings, parties, and other business-related events. Yachting, however, has a bad cultural connotation as compared to other activities in a wealthy society.

According to market research, affluent Chinese people like golf, swimming, spas, and yoga as leisure activities, since they are well-known in Chinese culture for providing health benefits , and are thus appealing. Yachting, on the other hand, does not provide comparable physical benefits in the traditional Chinese context. Such cultural premises are fundamental when considering the gap between target customers and the industry culture.

All things considered, it is not impossible for Chinese customers to shift their perspective since the country’s shopping habits and tastes are fast changing because of the ongoing rise of HNWIs. This means that tastes are subject to change and may be molded if an industry pursues them aggressively. In reality, a lack of brand familiarity and awareness provides first-mover brand opportunities.

The future of China’s yacht industry

All in all, between financial crackdowns and setting up zones such as Hainan FTZ, what is the right space for the yacht market to develop? China’s financial crackdowns continued throughout 2021, with Beijing slamming for-profit education, tanking Ant Financial and Didi IPOs, or bringing the entertainment and gaming business under control, and harnessing local digital titans. As a result, in the era of “Common Prosperity,” it’s worth considering whether China’s yacht market can take off and grow.

Yet, the central government’s desire to boost consumption and encourage tourism (including yacht tourism) creates unprecedented potential for the boat sector in the coming years, at least for small-to-mid-sized boats. The formation of the Hainan Free Trade Zone and the development of a new port have the potential to turn the island into a hub for China’s yacht culture. The number of registered boats in Sanya has increased from 10 to 500 in the previous decade alone, and yacht rental services have grown in popularity in China, enhancing yacht culture among both the Chinese middle and high-income classes.

Further, according to the Guidelines on Accelerating the Development of Cruise and Yacht Equipment and the Industry (Guidelines) jointly released by the MIIT and other ministries on August 18, 2 0 22 , there are four development goals to achieve in the yacht industry by 2025: improving the design and construction capacity, refining the foundation of the equipment industry, expanding the demands in the consumer market, and strengthening cooperation and talent cultivation. Sanya is expected to be transformed into a home port for international cruises, outlining several international first-class cruise tourism destinations. Priority is attached to the development of water tourism resources in areas such as the Circum-Bohai Sea Economic Zone, the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, the coastal city cluster that links Guangdong, Fujian and Zhejiang, the Hainan Free Trade Port, the Yangtze River Economic Belt, the Pearl River-West River Economic Belt, and the Grand Canal Cultural Belt. Meanwhile, Hainan is encouraged to pilot a yacht leasing business. The Guidelines also called for building teams of professional talents along the whole industry chain, covering the design, construction, operation, and management of cruises, yachts , and tourist passenger ships, as well as related tourism services and legal consulting.

Catering to specific needs

With China’s yachting culture still in its infancy, yacht makers should concentrate on meeting the expectations of Chinese clientele, from emphasizing the design of entertaining rooms to making it easier to hire superyachts on a short-term basis. The scarcity of skilled Chinese Mandarin-speaking specialists and Chinese designers, on the other hand, is stifling the growth of China’s boat sector. Foreign shipbuilding businesses should tailor their offerings to the demands and preferences of Chinese boat buyers, keeping in mind lifestyle and cultural preferences.

For example, Chinese yacht owners seldom spend the night on board and prefer boats with leisure and recreational amenities like KTV (karaoke) rooms. Catering to such needs, which are specific to the Chinese clientele, is an essential part of challenging cultural differences and securing a spot in such a promising market.

This article was first published on June 21, 2022 and last updated on September 29, 2022.

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates . The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at [email protected] . Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam , Indonesia , Singapore , United States , Germany , Italy , India , and Russia , in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative . We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines , Malaysia , Thailand , Bangladesh .

- Previous Article China Resumes License Approval: What’s Next for its Gaming Industry? (updated)

- Next Article Hong Kong Lifts Mandatory Hotel Quarantine for Inbound Travelers – What to Know Before You Go

Our free webinars are packed full of useful information for doing business in China.

DEZAN SHIRA & ASSOCIATES

Meet the firm behind our content. Visit their website to see how their services can help your business succeed.

Want the Latest Sent to Your Inbox?

Subscribing grants you this, plus free access to our articles and magazines.

Get free access to our subscriptions and publications

Subscribe to receive weekly China Briefing news updates, our latest doing business publications, and access to our Asia archives.

Your trusted source for China business, regulatory and economy news, since 1999.

Subscribe now to receive our weekly China Edition newsletter. Its free with no strings attached.

Not convinced? Click here to see our last week's issue.

Search our guides, media and news archives

Type keyword to begin searching...

BestCrosswordsAnswers.com

A yacht going astray in China crossword clue

Searching our database for: A yacht going astray in China crossword clue answers and solutions. This crossword clue was last seen today on Best Daily Cryptic Crossword December 1 2022. Found 1 possible answer matching the query A yacht going astray in China that you searched for. Kindly check the possible solution below and if it’s not what you are looking for then use the search form to try again.

A yacht going astray in China

Already solved this crossword clue? Go back and see the other clues for Best Daily Cryptic Crossword December 1 2022 Answers.

Yachting in China

It is believed that the Chinese have a different perception of yachting compared to Europeans since they have not been exposed to it for a long time, lacking the necessary knowledge and experience. However, as time passes, the Chinese empire is starting to participate in water sports and recreation.

Despite the abundance of information available about China, much of what is happening in the country remains a mystery to us. We have tried to explore how the yachting industry on the mainland is faring, without touching on specific topics like Taiwan and Hong Kong, which merit a separate discussion.

Surprises in China

The number of affluent people in China is rapidly increasing. In 2013, China ranked second globally in terms of the number of millionaires – 2,378,000 people; an 82% increase from the previous year. Furthermore, half of these millionaires, according to research by Barclays and Ledbury Research, plan to move to other countries over the next five years, with less than 1% of them purchasing yachts. There are several reasons for this relatively low demand, including a negative attitude towards yacht purchases due to national culture, high taxes (up to 40% on imported vessels), and weak yacht legislation. Additionally, not every location is suitable for yachting, with coasts and large rivers heavily polluted and congested with commercial and other vessels. As such, many people prefer to keep their boats in Hong Kong, where the infrastructure is more developed.

Between 2006 and 2010, China’s yachting industry grew from virtually nothing to $3.4 billion (a 732% increase). There is a rapidly growing middle class in the country (15% of the working population, with 1% annual growth), and while many of these people cannot afford Rolls-Royces, they are interested in yachts and tend to purchase relatively inexpensive locally produced models costing $80-160 thousand.

At exhibitions, European shipyard and designer representatives have noted that the Chinese use yachts differently from Europeans. They are not inclined towards long cruises or accommodation on board, and yachts serve primarily for entertaining friends and business clients. Salons are used for karaoke, dancing, board games, and cinemas. As such, local preferences regarding layouts and design are quite distinct. After having fun, the Chinese typically go home and do not spend the night on board their yachts.

China also faces the issue of its reputation as a manufacturer of cheap consumer goods. Not all potential buyers are prepared to accept that their luxury yacht is made in China. Although the quality of Chinese boats is not always satisfactory by European and American standards, local shipyards are steadily improving in this regard, including by seeking the expertise of foreign specialists. Conversely, there are people who are willing to compromise on interior detailing but get a yacht that is longer than what can be built in Europe for their money. Despite this, China has already entered the top ten countries producing yachts over 24 meters long and is actively creating new brands with its own design, closing the gap with Europe not only in quality but also in price.

Market Conditions

Currently, the combined yacht market of Europe and the United States accounts for 95% of the world market. Although China recovered more quickly than the Old and New Worlds from the economic crisis of 2008, many large manufacturers believed that massive expansion into Asia would help them weather hard times. However, the growth of the yacht market in China began back in 2005, and by 2020, its turnover should reach $10 billion (about 100,000 yachts) according to the most conservative estimates, and up to $30 billion according to the most optimistic estimates. The question is whether this country can achieve it.

In 2013, China declared it the Year of Marine Tourism. The development plan for this industry emphasized the formation of yachting and related infrastructure. At that time, only about 3,000 yachts were registered in the country, which meant one vessel for every 452,000 people. For comparison, in Italy, this ratio is 1:100. However, it should be noted that due to imperfect legislation, a significant number of unregistered yachts are “living” in China.