Please use a modern browser to view this website. Some elements might not work as expected when using Internet Explorer.

- Landing Page

- Luxury Yacht Vacation Types

- Corporate Yacht Charter

- Tailor Made Vacations

- Luxury Exploration Vacations

- View All 3594

- Motor Yachts

- Sailing Yachts

- Classic Yachts

- Catamaran Yachts

- Filter By Destination

- More Filters

- Latest Reviews

- Charter Special Offers

- Destination Guides

- Inspiration & Features

- Mediterranean Charter Yachts

- France Charter Yachts

- Italy Charter Yachts

- Croatia Charter Yachts

- Greece Charter Yachts

- Turkey Charter Yachts

- Bahamas Charter Yachts

- Caribbean Charter Yachts

- Australia Charter Yachts

- Thailand Charter Yachts

- Dubai Charter Yachts

- Destination News

- New To Fleet

- Charter Fleet Updates

- Special Offers

- Industry News

- Yacht Shows

- Corporate Charter

- Finding a Yacht Broker

- Charter Preferences

- Questions & Answers

- Add my yacht

Private YACHT

NOT FOR CHARTER*

SIMILAR YACHTS FOR CHARTER

VIEW SIMILAR YACHTS

Or View All luxury yachts for charter

- Luxury Charter Yachts

- Motor Yachts for Charter

- Amenities & Toys

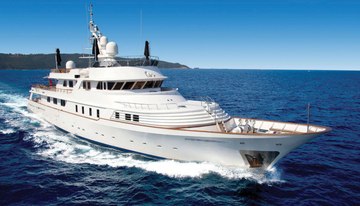

ACHILLES yacht NOT for charter*

55m / 180'5 | crn | 1984 / 2016.

Owner & Guests

Cabin Configuration

- Previous Yacht

Special Features:

- Impressive 4,606nm range

- Two VIP cabins

- Lloyds Register classification

- Interior design from Zuretti

- Sleeps 12 overnight

The 55m/180'5" motor yacht 'Achilles' (ex. New Santa Mary) was built by CRN in Italy. Her interior is styled by French designer design house Zuretti and she was completed in 1984. This luxury vessel's exterior design is the work of CRN and she was last refitted in 2016.

Guest Accommodation

Achilles has been designed to comfortably accommodate up to 12 guests in 7 suites comprising two VIP cabins. She is also capable of carrying up to 13 crew onboard to ensure a relaxed luxury yacht experience.

Onboard Comfort & Entertainment

Her features include WiFi and air conditioning.

Range & Performance

Achilles is built with a steel hull and aluminium superstructure, with teak decks. Powered by twin diesel Deutz (BV8M628) 2,200hp engines, she comfortably cruises at 13 knots, reaches a maximum speed of 17 knots with a range of up to 4,606 nautical miles from her 135,000 litre fuel tanks at 14 knots. Her water tanks store around 27,000 Litres of fresh water. She was built to Lloyds Register classification society rules.

PRIVATE YACHT - "Achilles" IS NOT FOR CHARTER

Sorry, motor yacht "Achilles" is a strictly Private yacht and is NOT available for Charter. Click here to view similar yachts for charter , or contact your Yacht Charter Broker for information about renting another luxury charter yacht.

"Yacht Charter Fleet" is a free information service, if your vessel changes its status, and does become available for charter, please contact us with details and photos and we will update our records.

Achilles Photos

NOTE to U.S. Customs & Border Protection

NOTE TO U.S. CUSTOMS & BORDER PROTECTION

Due to the international and fluid nature of the yachting business and the fact there is no global central industry listing service to which all charter yachts subscribe it is impossible to ascertain a truly up-to-date view of the market. We are a news and information service and not always informed when yachts leave the charter market, or when they are recently sold and renamed it is not clear if they are still for charter. Whilst we use our best endeavors to maintain accurate information, the existence of a listing on this website should in no way supersede official documentation supplied by representatives of a yacht.

Specification

M/Y Achilles

SIMILAR LUXURY YACHTS FOR CHARTER

Here are a selection of superyachts which are similar to Achilles yacht which are believed to be available for charter. To view all similar luxury charter yachts click on the button below.

52m | Mie Zosen

from $192,500 p/week

50m | Benetti

from $159,000 p/week ♦︎

50m | Feadship

from $128,000 p/week ♦︎

56m | Feadship

from $187,000 p/week ♦︎

51m | Fr. Schweers Shipyard

POA ♦︎

53m | Feadship

from $213,000 p/week ♦︎

O'Natalina

56m | Picchiotti

from $155,000 p/week ♦︎

Shake N Bake TBD

50m | Campanella

from $160,000 p/week ♦︎

Wind of Fortune

from $134,000 p/week ♦︎

As Featured In

The YachtCharterFleet Difference

YachtCharterFleet makes it easy to find the yacht charter vacation that is right for you. We combine thousands of yacht listings with local destination information, sample itineraries and experiences to deliver the world's most comprehensive yacht charter website.

San Francisco

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Follow us on Instagram

- Find us on LinkedIn

- Add My Yacht

- Affiliates & Partners

Popular Destinations & Events

- St Tropez Yacht Charter

- Monaco Yacht Charter

- St Barts Yacht Charter

- Greece Yacht Charter

- Mykonos Yacht Charter

- Caribbean Yacht Charter

Featured Charter Yachts

- Maltese Falcon Yacht Charter

- Wheels Yacht Charter

- Victorious Yacht Charter

- Andrea Yacht Charter

- Titania Yacht Charter

- Ahpo Yacht Charter

Receive our latest offers, trends and stories direct to your inbox.

Please enter a valid e-mail.

Thanks for subscribing.

Search for Yachts, Destinations, Events, News... everything related to Luxury Yachts for Charter.

Yachts in your shortlist

Stay afloat with Achilles

Achilles inflatable boats.

Every Achilles boat is made with our own proven four-layered fabric reinforced with Achilles CSM fabric. We are one of the few inflatable boat companies that manufacture our own fabric, and have for over 30 years. This ensures consistent quality year-to-year and boat-to-boat.

Boat Models Dinghies

A lot of quality in a small package.

These two and four-person boats go from their handy carry bags to fully equipped dinghies in just minutes.

Boat Models Sport Tenders

Lightweight, easy-to-stow tenders.

Value packed, roll-up option for boaters who need the space-saving convenience of a lightweight easy-to-stow tender.

Boat Models Rigid Hulls

Sleek, euro-style tubes.

These deluxe hard bottom inflatables offer boaters the best combination of style, performance and functionality.

Boat Models Sport Boats

Rugged and roomy.

These versatile aluminum and wood-floored boats are the perfect solution for a range of uses.

Boat Models Sport Utility

Built tough to work hard.

A number of commercial grade features such as recessed valves and a full-length, protective wear patch combine to makes these boats the right choice for the toughest marine uses.

Boat Models Commercial & Rescue

Rapid deployment rescue series.

A versatile utility boat that is ready to go in minutes.

Boats & Parts

Check out our boat models & search for parts

Catalogs & Manuals

Get your 2024 Catalog from Achilles Inflatables

Download Now Order Yours Now

Find anything, super fast.

- Destinations

- Documentaries

Motor Yacht

Achilles, previously known as Princess Lauren and Lady Fiesta is a 55.30m motor yacht, custom built in 1984 by CRN. The yacht has exterior styling by CRN, with interior design by Zuretti. She was last refitted in 2008 by Alpha Marine.

Achilles has a steel hull and aluminium superstructure with a beam of 8.20m (26.90ft) and a 4m (13.12ft) draft.

Achilles initially received a refit from Alpha Marine in 1997. Extensive work on the interior and exterior included the addition of a swimming platform. The hull of the vessel was also extended by 3.20m. In 2008 Alpha Marine carried out the project development and management in order to successfully complete numerous works for an extensive refit to Achilles’ interior accommodation areas and exterior spaces. Performance + Capabilities Achilles is capable of 20 knots flat out, with a range of 4000 nautical miles. Achilles Accommodation Achilles offers accommodation for up to 16 guests in two suites. She is also capable of carrying up to 13 crew members onboard to ensure a relaxed luxury yacht experience.

- Yacht Builder CRN View profile

- Interior Designer Zuretti No profile available

Yacht Specs

Other crn yachts, related news.

ACHILLES CRN

- Inspiration

ACHILLES has 29 Photos

Western Mediterranean

Achilles news.

Gorgeous 46m Sanlorenzo Motor Yacht ...

Similar yachts.

PURPOSE | From EUR€ 270,000/wk

- Yachts >

- All Yachts >

- All Motor Yachts Over 100ft/30m >

If you have any questions about the ACHILLES information page below please contact us .

A General Description of Motor Yacht ACHILLES

This motor yacht ACHILLES is a 55 metre 181 (ft) impressive steel vessel which was newly built at CRN Yachts (Ferretti Group) and devised from the design board of Crn and Martin Francis. Accommodating 16 passengers and 13 qualified crew, motor yacht ACHILLES was named Genros; New Santa Mary; Azteca Ii; Lady Azteca; Princess Lauren; Lady Fiesta. The naval architect responsible for the design for this ship is Crn and Martin Francis. Her interior styling is the work of Martin Francis/Zuretti Interior Design.

The Construction & Design of Luxury Yacht ACHILLES

Crn was the naval architect firm involved in the technical superyacht design work for ACHILLES. Her interior design was realised by Martin Francis/Zuretti Interior Design. Crn and Martin Francis is also associated with the yacht wider design collaboration for this boat. Italy is the country that Crn Yachts (Ferretti Group) built their new build motor yacht in. After official launch in 1984 in Ancona she was then delivered on to the owner having completed sea trials and testing. The hull was built out of steel. The motor yacht main superstructure is made for the most part using aluminium. With a width of 8.2 metres or 26.9 feet ACHILLES has spacious room. She has a fairly deep draught of 4m (13.12ft). She had refit improvement and modification completed in 2009.

Range & Speeds And Engineering Figures On M/Y ACHILLES:

Fitted with twin DEUTZ-MWM diesel main engines, ACHILLES will attain a top speed of 17 knots. For propulsion ACHILLES has twin screw propellers. She also has an efficient range of 4000 miles when motoring at her cruise speed of 14 knots. Her total HP is 4400 HP and her total Kilowatts are 3238. As for the yacht’s stabalisers she was built with Vosper.

Guest Accommodation On Aboard Superyacht ACHILLES:

The notable luxury yacht M/Y ACHILLES can accommodate as many as 16 people and 13 crew.

A List of the Specifications of the ACHILLES:

Miscellaneous yacht details.

Around October 2009 ACHILLES cruised to Palma, in Spain. This motor yacht also navigated the location near Illes Balears during the month of Sept 2009. An Unknown Brand is the model of air con used in the interior. She has a teak deck.

ACHILLES Disclaimer:

The luxury yacht ACHILLES displayed on this page is merely informational and she is not necessarily available for yacht charter or for sale, nor is she represented or marketed in anyway by CharterWorld. This web page and the superyacht information contained herein is not contractual. All yacht specifications and informations are displayed in good faith but CharterWorld does not warrant or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the current accuracy, completeness, validity, or usefulness of any superyacht information and/or images displayed. All boat information is subject to change without prior notice and may not be current.

Quick Enquiry

“We reinvented the idea of Bespoke”. 'CRN devotes maximum attention to craftsmanship and style, representing the true added value of Designed & Made in Italy products.'

NEXT CHAPTER | From US$ 325,000/wk

TURQUOISE | From US$ 300,000/wk

AFTER YOU | From US$ 350,000/wk

The global authority in superyachting

- NEWSLETTERS

- Yachts Home

- The Superyacht Directory

- Yacht Reports

- Brokerage News

- The largest yachts in the world

- The Register

- Yacht Advice

- Yacht Design

- 12m to 24m yachts

- Monaco Yacht Show

- Builder Directory

- Designer Directory

- Interior Design Directory

- Naval Architect Directory

- Yachts for sale home

- Motor yachts

- Sailing yachts

- Explorer yachts

- Classic yachts

- Sale Broker Directory

- Charter Home

- Yachts for Charter

- Charter Destinations

- Charter Broker Directory

- Destinations Home

- Mediterranean

- South Pacific

- Rest of the World

- Boat Life Home

- Owners' Experiences

- Interiors Suppliers

- Owners' Club

- Captains' Club

- BOAT Showcase

- Boat Presents

- Events Home

- World Superyacht Awards

- Superyacht Design Festival

- Design and Innovation Awards

- Young Designer of the Year Award

- Artistry and Craft Awards

- Explorer Yachts Summit

- Ocean Talks

- The Ocean Awards

- BOAT Connect

- Between the bays

- Golf Invitational

- Boat Pro Home

- Pricing Plan

- Superyacht Insight

- Product Features

- Premium Content

- Testimonials

- Global Order Book

- Tenders & Equipment

CRN Motor Yacht Achilles For Sale

The 55.2 metre motor yacht Achilles has been listed for sale by Fergus Torrance at Torrance Yachts.

Built in steel and aluminium by Italian yard CRN to a design by Martin Francis , Achilles was delivered in 1984 and has had the same owner for the past 15 years with a continuous programme of upgrades and refits, most recently in 2018. Accommodation in a spacious interior by Francois Zuretti is for 12 guests in seven cabins comprising a main deck master suite, two VIP suites, two doubles and two twins. All guest cabins have entertainment centres, television screens and en suite bathroom facilities while a further eight cabins sleep 13 crew aboard this yacht for sale .

The main saloon features comfortable seating for up to 12 guests, a bar and an entertainment centre including a 55-inch Sharp HD television screen on a rise and fall mechanism and a Bose stereo surround sound system.

On the upper deck, a lounge and bar area offer excellent 360-degree views and an outdoor dining area is accessible through two sliding glass doors. Extensive use of glass is a special feature on this yacht, with guests always kept in touch with the surrounding seascape. Her top speed is 17 knots and she boasts a maximum cruising range of 4,000 nautical miles at 14 knots with power coming from two 2,200hp Deutz BV8M628 diesel engines.

Lying in Genoa, Italy, Achilles is asking €6,500,000.

More about this yacht

Similar yachts for sale, more stories, most popular, from our partners, sponsored listings.

- Yachts for sale

- Yachts for charter

- Brokerage News

- Yacht Harbour

- Yacht Achilles

About Achilles

Contact agent, specifications, similar yachts.

New listings

All Achilles Boats For Sale

Achilles Yachts

Achilles yachts were built by Chris Butler of Butler Mouldings, initially from a re-developed Ajax design created by Oliver Lee (Achilles 24) based in Hackney, East London, before designing the later models of the Achilles himself. The Achilles 24's success brought a move to Swansea, South Wales, where larger premises coped with the demand for the Achilles 24, and subsequently the other Achilles yachts in the range of which over 1500 were built. The company's history dates back to 1954, though the Achilles range of yachts was built from around 1968 when Chris Butler and Oliver Lee conspired to produce a fast race-style yacht with better accommodation. The production of Achilles yachts ceased around 1989 when its interests grew more into producing submersible craft for use on oil rigs and later closed when Chris Butler retired.

Achilles is renowned as fast cruiser-racer yachts and has successfully competed in many ocean races, sometimes being sailed single-handedly in competitions. The family of yachts have a good pedigree, and their build quality and safety are unquestionable. Achilles yachts are popular due to their reputation, and their design hits a perfect balance between performance and accommodation.

Several yacht types have been manufactured under the name Achilles: Achilles 24, Achilles 840, Achilles 9m, Achilles 7m, Achilles 7.5m & Sparta. By far, the most popular was the Achilles 24, of which over 600 were said to have been produced, though later the 9m and the 840 became popular choices for those who wanted a more serious cruising yacht.

Updated By Network Yacht Brokers Barcelona March 2021

Achilles boats previously for sale

test456 0' 0"

Achillies ... 29' 9"

Achilles 840 27' 6"

Achilles 840 27' 9"

Achilles 750 24' 7"

Achilles 24 23' 8"

Achillies 24 23' 9"

- Croatia North

- Milford Haven

- Sell My Boat

- NYB Group Offices

- Become A Yacht Broker

- Manufacturers

- Privacy Policy

© 2004-24 Network Yacht Brokers

- Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

Achilles 24

- September 23, 2009

A seminal range of small but tough offshore cruisers

Product Overview

Price as reviewed:.

Chris Butler designed and built a seminal range of small but tough offshore cruisers that found themselves in all corners of the world. They sold in large numbers for the times (late 60s to late 70s). Performance across the range tended to be moderate to good and the interiors on the small side due to narrow beam, but their strong suit was sea-keeping and the ability to keep going in difficult conditions. Butler competed in AZAB and OSTAR races in the Achilles 24, which featured a bulbed fin keel. This gave the boat quite respectable speed and windward performance but a triple-keeled, shoal draught version was much more pedestrian. She has four berths, a small galley and a rudimentary toilet. Headroom was just 4ft 8in (1.37m). Most of the 350-plus built were originally sold without engines and many will still use outboards, but an inboard petrol engine was an option, usually quickly replaced with a small diesel. Factory-built boats were sound, strong but simple. The quality of the many home-built models will be variable.

Your Chesapeake Bay Boating Connection for 50+ years!

Any inflatable boat is only as good as it’s fabric — and for 40 years Achilles has been making the industry’s very best.

Achilles has always had the reputation for manufacturing one of the highest quality inflatable boats in the world. Any inflatable dealer will tell you that the quality of the boat begins and ends with its fabric — its durability, toughness and overall reliability. And it’s no surprise that Achilles sets the standard for manufacturing the boat fabric, used to craft its own premium line of inflatable boats, but often sold to be used in the construction of other inflatable boat brands.

Achilles proprietary fabric is constructed using 4 layers: two inner layers of Chlorprene for unsurpassed air retention, a core layer of heavy duty nylon for strength and rigidity and an exterior of chlorosulphonated polyethylene, or CSM, for toughness and ultimate durability. When combined, these 4 layers create an inflatable boat fabric with unsurpassed durability, resulting in : UV resistance, abrasion resistance, and resistance to oil and gas – all things that boats are subject to in the marine environment. Beyond fabric, inflatable boat construction matters to the overall integrity of the craft. This is why, all Achilles boats are hand-crafted with all seams glued and sealed — overlapping a full inch and reinforced with seam tape both inside and out. No one else takes so many steps to ensure seams will last, which is why Achilles offers an industry leading full 5-year warranty on fabric and seams — instilling even greater confidence in your inflatable boat purchase.

And, don’t be fooled be the cheaper, knock-off inflatables that are primarily constructed out of PVC based fabric. Yes, they are less expensive, but they are also lower quality with many different points of failure and compromised safety over time. Achilles should know, they also make and sell PVC fabric, but ONLY chose to construct their brand of boats using CSM — a better fabric that stands the test of time. This is the very reason why it was an easy decision to select Achilles as our ONLY inflatable boat brand partner — among the many choices that we had.

Come see why Tri-State Marine is excited to represent Achilles as our new inflatable brand partner. Dinghies, Sport Tenders, Rigid Hulls and Sport Utilities, we sell and service the full line of Achilles models — all powered by Yamaha Outboards. Whether you need a new inflatable by itself or a boat with a Yamaha motor, visit Tri-State Marine to consider all of your options.

Model In Showroom

Ls-ru series, sport tenders.

LSI-E Series

LSR-E Series

SPD-E Series

Rigid hulls.

HB-AL Series

HB-LX Series

HB-AX Series

HB-FX Series

Achilles Yacht Owners Association

This site is for all those who are interested in sailing yachts built by Butler Mouldings.

- A750 & Sparta

- Achilles Boats for Sale

- Gear for sale.

- Trip Reports

- Maintenance & restoration

- Seamanship, safety & equipment

- Origins of Achilles Yachts

Friday, February 9, 2024

A24 build dates required.

Cross posted from Facebook:

If people (other than Huw) have good build dates for their A24's I'll have a go at doing an updated version of the sail number vs date graph. Replies will need to be with me by early March as I will hopefully be off sailing from the middle of the month. (this cross posted to the web site & Flikr).

Wednesday, January 10, 2024

Any a840 availability for measuring the rudder and skeg.

Cross posted from the A840 page

I have lost my rudder and part of my skeg in a storm. Does anyone know where u could get the drawings. Also if anyone has an achilies 840 that is out of the water and within 100 miles of edinburgh, it would be great if i could take measurements. Many thanks Stuart

Wednesday, April 12, 2023

Possible delays in moderation.

If things go to plan I will be sailing from Saturday April 15th 2 - 4 months, if moderation action is required it may take a few days to get done depending on where I am.

sv-sancerre

Friday, February 3, 2023

Good news re admiralty charts.

The timetable for the withdrawal of our paper chart portfolio is to be extended.

In July last year, the UK Hydrographic Office announced its intention to withdraw ADMIRALTY Standard Nautical Charts (SNCs) and Thematic Charts from production by late 2026.

Having listened to user feedback, it has become clear that more time is required to address the needs of those specific users who do not yet have viable alternatives to paper chart products. We will continue to provide a paper chart service until at least 2030.

https://www.admiralty.co.uk/news/paper-chart-withdrawal

Tuesday, January 31, 2023

Calor gas discontinues its 4.5kg butane cylinders with update retracting..

This may impact some owners:

Calor Gas discontinues its 4.5kg butane cylinders - Practical Boat Owner (pbo.co.uk)

Update 12 April 2023:

Looks like they have changed their mind, from the Cruising Association.

"⚠️Member Alert⚠️

Calor Gas has decided to continue exchanging and refilling its 3.9kg propane and 4.5kg butane cylinders for the immediate future.

Thursday, December 8, 2022

Spammers please note.

To the yacht brokers, particularly those in the middle east, those offering yacht charters etc. who, or who's bots, have not yet twigged - adverts pretending to be comments on posts are not being accepted and are marked as spam so, with a bit of luck, Google will eventually block you from their platforms and save me the effort of reporting you.

Monday, September 26, 2022

Bedtime reading for achilles sailors - 1976 ostar.

Ian Wallace (A9m "Spearhead") has completed a labour of love transcribing two descriptions of the 1976 OSTAR, see Trip Reports.

2022 Achilles HB - 280 LX

Turn Your Curiosity Into Discovery

Latest facts.

Follistatin344 Peptide Considerations

Approach for Using 5 Tips To Help You Write Your Dissertation

40 facts about elektrostal.

Written by Lanette Mayes

Modified & Updated: 02 Mar 2024

Reviewed by Jessica Corbett

Elektrostal is a vibrant city located in the Moscow Oblast region of Russia. With a rich history, stunning architecture, and a thriving community, Elektrostal is a city that has much to offer. Whether you are a history buff, nature enthusiast, or simply curious about different cultures, Elektrostal is sure to captivate you.

This article will provide you with 40 fascinating facts about Elektrostal, giving you a better understanding of why this city is worth exploring. From its origins as an industrial hub to its modern-day charm, we will delve into the various aspects that make Elektrostal a unique and must-visit destination.

So, join us as we uncover the hidden treasures of Elektrostal and discover what makes this city a true gem in the heart of Russia.

Key Takeaways:

- Elektrostal, known as the “Motor City of Russia,” is a vibrant and growing city with a rich industrial history, offering diverse cultural experiences and a strong commitment to environmental sustainability.

- With its convenient location near Moscow, Elektrostal provides a picturesque landscape, vibrant nightlife, and a range of recreational activities, making it an ideal destination for residents and visitors alike.

Known as the “Motor City of Russia.”

Elektrostal, a city located in the Moscow Oblast region of Russia, earned the nickname “Motor City” due to its significant involvement in the automotive industry.

Home to the Elektrostal Metallurgical Plant.

Elektrostal is renowned for its metallurgical plant, which has been producing high-quality steel and alloys since its establishment in 1916.

Boasts a rich industrial heritage.

Elektrostal has a long history of industrial development, contributing to the growth and progress of the region.

Founded in 1916.

The city of Elektrostal was founded in 1916 as a result of the construction of the Elektrostal Metallurgical Plant.

Located approximately 50 kilometers east of Moscow.

Elektrostal is situated in close proximity to the Russian capital, making it easily accessible for both residents and visitors.

Known for its vibrant cultural scene.

Elektrostal is home to several cultural institutions, including museums, theaters, and art galleries that showcase the city’s rich artistic heritage.

A popular destination for nature lovers.

Surrounded by picturesque landscapes and forests, Elektrostal offers ample opportunities for outdoor activities such as hiking, camping, and birdwatching.

Hosts the annual Elektrostal City Day celebrations.

Every year, Elektrostal organizes festive events and activities to celebrate its founding, bringing together residents and visitors in a spirit of unity and joy.

Has a population of approximately 160,000 people.

Elektrostal is home to a diverse and vibrant community of around 160,000 residents, contributing to its dynamic atmosphere.

Boasts excellent education facilities.

The city is known for its well-established educational institutions, providing quality education to students of all ages.

A center for scientific research and innovation.

Elektrostal serves as an important hub for scientific research, particularly in the fields of metallurgy, materials science, and engineering.

Surrounded by picturesque lakes.

The city is blessed with numerous beautiful lakes, offering scenic views and recreational opportunities for locals and visitors alike.

Well-connected transportation system.

Elektrostal benefits from an efficient transportation network, including highways, railways, and public transportation options, ensuring convenient travel within and beyond the city.

Famous for its traditional Russian cuisine.

Food enthusiasts can indulge in authentic Russian dishes at numerous restaurants and cafes scattered throughout Elektrostal.

Home to notable architectural landmarks.

Elektrostal boasts impressive architecture, including the Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord and the Elektrostal Palace of Culture.

Offers a wide range of recreational facilities.

Residents and visitors can enjoy various recreational activities, such as sports complexes, swimming pools, and fitness centers, enhancing the overall quality of life.

Provides a high standard of healthcare.

Elektrostal is equipped with modern medical facilities, ensuring residents have access to quality healthcare services.

Home to the Elektrostal History Museum.

The Elektrostal History Museum showcases the city’s fascinating past through exhibitions and displays.

A hub for sports enthusiasts.

Elektrostal is passionate about sports, with numerous stadiums, arenas, and sports clubs offering opportunities for athletes and spectators.

Celebrates diverse cultural festivals.

Throughout the year, Elektrostal hosts a variety of cultural festivals, celebrating different ethnicities, traditions, and art forms.

Electric power played a significant role in its early development.

Elektrostal owes its name and initial growth to the establishment of electric power stations and the utilization of electricity in the industrial sector.

Boasts a thriving economy.

The city’s strong industrial base, coupled with its strategic location near Moscow, has contributed to Elektrostal’s prosperous economic status.

Houses the Elektrostal Drama Theater.

The Elektrostal Drama Theater is a cultural centerpiece, attracting theater enthusiasts from far and wide.

Popular destination for winter sports.

Elektrostal’s proximity to ski resorts and winter sport facilities makes it a favorite destination for skiing, snowboarding, and other winter activities.

Promotes environmental sustainability.

Elektrostal prioritizes environmental protection and sustainability, implementing initiatives to reduce pollution and preserve natural resources.

Home to renowned educational institutions.

Elektrostal is known for its prestigious schools and universities, offering a wide range of academic programs to students.

Committed to cultural preservation.

The city values its cultural heritage and takes active steps to preserve and promote traditional customs, crafts, and arts.

Hosts an annual International Film Festival.

The Elektrostal International Film Festival attracts filmmakers and cinema enthusiasts from around the world, showcasing a diverse range of films.

Encourages entrepreneurship and innovation.

Elektrostal supports aspiring entrepreneurs and fosters a culture of innovation, providing opportunities for startups and business development.

Offers a range of housing options.

Elektrostal provides diverse housing options, including apartments, houses, and residential complexes, catering to different lifestyles and budgets.

Home to notable sports teams.

Elektrostal is proud of its sports legacy, with several successful sports teams competing at regional and national levels.

Boasts a vibrant nightlife scene.

Residents and visitors can enjoy a lively nightlife in Elektrostal, with numerous bars, clubs, and entertainment venues.

Promotes cultural exchange and international relations.

Elektrostal actively engages in international partnerships, cultural exchanges, and diplomatic collaborations to foster global connections.

Surrounded by beautiful nature reserves.

Nearby nature reserves, such as the Barybino Forest and Luchinskoye Lake, offer opportunities for nature enthusiasts to explore and appreciate the region’s biodiversity.

Commemorates historical events.

The city pays tribute to significant historical events through memorials, monuments, and exhibitions, ensuring the preservation of collective memory.

Promotes sports and youth development.

Elektrostal invests in sports infrastructure and programs to encourage youth participation, health, and physical fitness.

Hosts annual cultural and artistic festivals.

Throughout the year, Elektrostal celebrates its cultural diversity through festivals dedicated to music, dance, art, and theater.

Provides a picturesque landscape for photography enthusiasts.

The city’s scenic beauty, architectural landmarks, and natural surroundings make it a paradise for photographers.

Connects to Moscow via a direct train line.

The convenient train connection between Elektrostal and Moscow makes commuting between the two cities effortless.

A city with a bright future.

Elektrostal continues to grow and develop, aiming to become a model city in terms of infrastructure, sustainability, and quality of life for its residents.

In conclusion, Elektrostal is a fascinating city with a rich history and a vibrant present. From its origins as a center of steel production to its modern-day status as a hub for education and industry, Elektrostal has plenty to offer both residents and visitors. With its beautiful parks, cultural attractions, and proximity to Moscow, there is no shortage of things to see and do in this dynamic city. Whether you’re interested in exploring its historical landmarks, enjoying outdoor activities, or immersing yourself in the local culture, Elektrostal has something for everyone. So, next time you find yourself in the Moscow region, don’t miss the opportunity to discover the hidden gems of Elektrostal.

Q: What is the population of Elektrostal?

A: As of the latest data, the population of Elektrostal is approximately XXXX.

Q: How far is Elektrostal from Moscow?

A: Elektrostal is located approximately XX kilometers away from Moscow.

Q: Are there any famous landmarks in Elektrostal?

A: Yes, Elektrostal is home to several notable landmarks, including XXXX and XXXX.

Q: What industries are prominent in Elektrostal?

A: Elektrostal is known for its steel production industry and is also a center for engineering and manufacturing.

Q: Are there any universities or educational institutions in Elektrostal?

A: Yes, Elektrostal is home to XXXX University and several other educational institutions.

Q: What are some popular outdoor activities in Elektrostal?

A: Elektrostal offers several outdoor activities, such as hiking, cycling, and picnicking in its beautiful parks.

Q: Is Elektrostal well-connected in terms of transportation?

A: Yes, Elektrostal has good transportation links, including trains and buses, making it easily accessible from nearby cities.

Q: Are there any annual events or festivals in Elektrostal?

A: Yes, Elektrostal hosts various events and festivals throughout the year, including XXXX and XXXX.

Was this page helpful?

Our commitment to delivering trustworthy and engaging content is at the heart of what we do. Each fact on our site is contributed by real users like you, bringing a wealth of diverse insights and information. To ensure the highest standards of accuracy and reliability, our dedicated editors meticulously review each submission. This process guarantees that the facts we share are not only fascinating but also credible. Trust in our commitment to quality and authenticity as you explore and learn with us.

Share this Fact:

Rupert Murdoch reportedly spent a night on a gurney in a hospital parking lot after he broke his back falling on son Lachlan's yacht

- Rupert Murdoch reportedly broke his back after he fell while aboard his son Lachlan's yacht in 2018.

- The media giant also reportedly tore an Achilles tendon and struggled with cases of pneumonia and COVID-19.

- A new report from Vanity Fair detailed previously unreported health scares experienced by the 92-year-old media mogul.

Rupert Murdoch reportedly fell and sustained serious injuries while aboard his son's yacht in 2018, an incident that led the media mogul to spend a night in a European hospital parking lot, waiting under a tent until he could be flown back to the US.

A lengthy new report from Vanity Fair detailed several previously unreported health scares experienced by the 92-year-old CEO and chairman of News Corporation, including a broken back from the yacht fall, a torn Achilles, seizures, and bouts with pneumonia and COVID-19.

Citing sources close to the family, Vanity Fair reported that the media mogul and his then-wife Jerry Hall were on Lachlan Murdoch's yacht in January 2018 when Rupert fell while using the bathroom overnight, waking Hall, who found him in pain on the floor.

Related stories

The yacht, which was sailing near Guadeloupe, reportedly docked at the nearest island to take Murdoch to the hospital, per Vanity Fair.

However, the hospital on the island was allegedly closed due to a recent fire, so Murdoch was forced to spend a night in the hospital parking lot on a gurney under a tent until a family plane arrived to fly him back to the states to receive medical care.

Sources close to the family said he was in critical condition, and "kept almost dying," according to Vanity Fair.

The incident reportedly left Murdoch bedridden for months, during which he was spoon fed by Hall as he recovered. According to the report, Murdoch later tore an Achilles tendon after tripping over a box in March 2019, leaving him wheelchair-bound. He also reportedly spent time in the hospital with pneumonia and seizures during this convalescent period.

Murdoch was said to be much more careful during the pandemic than Fox News hosts were advising the public to be, and people close to the family told Vanity Fair that he and Hall stayed home for months at a time in 2020. Murdoch was also one of the first people to receive a dose of the COVID-19 vaccine as Fox hosts criticized preventative measures like the vaccines and masks.

Despite his precautions, Murdoch was reportedly diagnosed with COVID-19 just days before his granddaughter's wedding in July 2022, and appeared "very weak," with Lachlan "holding him up to get from place to place," a guest told Vanity Fair.

Representatives for Murdoch and Hall did not immediately respond to Insider's request for comment.

- Main content

essay on management of grief

Literary theory and criticism.

Home › Literature › Analysis of Bharati Mukherjee’s The Management of Grief

Analysis of Bharati Mukherjee’s The Management of Grief

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on May 29, 2021

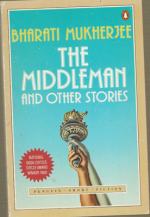

The Management of Grief is collected in The Middleman and Other Stories (1988), winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award. The idea of “middlemen” is central to these stories of immigrant experience; Bharati Mukherjee presents characters in fl ux as they cope with their positions: They are between cultures, between lifestyles, between the old and the new, between the persons they used to be and the persons they are becoming in their new lives. “The Management of Grief” is a fictional depiction of the June 25, 1985, terrorist bombing of an Air India Boeing 747 en route from Canada to Bombay via London’s Heathrow Airport. The crash killed all 329 passengers, most of whom were Canadian Indians. Mukherjee and her husband, Clark Blaise, had researched and written a book on the tragedy ( The Sorrow and the Terror [1987]). In an interview with the scholar Beverley Beyers-Pevitts, Bharati Mukherjee reminisces about the composition of this story: “ ‘The Management of Grief,’ the one which is most anthologized, I did in two sittings. Almost all of it was written in one sitting because I was so ready to tell that story” (190).

In the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, the tale opens in Toronto in the kitchen of Shaila Bhave, a Hindu Canadian who has lost her husband, Vikram, and two sons, Vinod and Mithun, in the crash. Through Shaila, the central character, Mukherjee illuminates not only the community’s immediate reactions to the horrific event but also the Indian values and cultural differences that the well-meaning Canadian social worker Judith Templeton struggles vainly to comprehend. Valium mutes Shaila’s own grief as she commiserates with her neighbor Kusum, whose husband, Satish, and a talented daughter were crash victims. Kusum is confronted by her Westernized daughter Pam, who had refused to travel to India, preferring to stay home and work at McDonald’s; Pam now accuses her mother of favoring her dead sister. As well-intentioned neighbors make tea and answer phone calls, Judith Templeton asks Shaila to help her communicate with the hundreds of Indian-born Canadians affected by the tragedy, some of whom speak no English: “There are some widows who’ve never handled money or gone on a bus, and there are old parents who still haven’t eaten or gone outside their bedrooms” (183). Judith appeals to Shaila because “All the people said, Mrs. Bhave is the strongest person of all” (183).

Bharati Mukherjee/The New York Times

Shaila agrees to try to help on her return from Ireland, site of the plane crash. While there she describes the difficulties of Kusum, who eventually finds acceptance of her loss through her swami, and of Dr. Ranganathan, a Montreal electrical engineer whose entire family perished. Shaila is in denial and is actually relieved when she cannot identify as hers any of the young boys’ bodies whose photos are presented to her. From Ireland, Shaila and Kusum fl y to Bombay, where Shaila finally screams in frustration at a customs official and then notes, “One [sic] upon a time we were well brought up women; we were dutiful wives who kept our heads veiled, our voices shy and sweet” (189). While with her grandmother and parents, Shaila describes their differences—the grandmother observes Hindu traditions while her parents rebelled against them— and sees herself as “trapped between two modes of knowledge. At thirty-six, I am too old to start over and too young to give up. Like my husband’s spirit, I flutter between two worlds” (189). She reenters her old life for a while, playing bridge in gymkhana clubs, riding ponies on trails, attending tea dances, and observing that the widowers are already being introduced to “new bride candidates” (190). She considers herself fortunate to be an “unlucky widow,” who, according to custom, is ineligible for remarriage. Instead, in a Hindu temple, her husband appears to her and tells her to “ finish what we started together ” (190).

And so, unlike Kusum, who moves to an ashram in Hardwar, Shaila returns to Toronto, sells her house at a profi t, and moves to an apartment. Once again, Judith seeks her help, this time with an old Sikh couple who refuse to accept their sons’ deaths and therefore refuse all government aid, despite being plunged into darkness when the electric company cuts off their power. Shaila cannot explain to Judith, who as a social worker is immersed in the four “stages” of grief, that as a Hindu she cannot communicate with this Sikh couple, particularly because Sikhs were probably responsible for the bombing of the Air India fl ight. Still, she understands their hope that their sons will reappear and has difficulty sympathizing with Judith’s government forms and legalities. Shaila leaves Judith, hears her family’s voices exhorting her to be brave and to continue her life, and, on a hopeful note, begins walking toward whatever her new life will present.

Analysis of Bharati Mukherjee’s Stories

BIBLIOGRAPHY Beyers-Pevitts, Beverley. “An Interview with Bharati Mukherjee.” In Speaking of the Short Story: Interviews with Contemporary Writers. Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 1997. Carb, Alison B. “An Interview with Bharati Mukherjee.” Massachusetts Review 29 (1988–1999): 645–654. Connell, Michael, Jessie Grearson, and Tom Grimes. “An Interview with Bharati Mukherjee.” Iowa Review 20, no. 3 (Fall 1990): 7–32. Hancock, Geoff. “An Interview with Bharati Mukherjee.” Canadian Fiction Magazine 59 (1987): 30–44. Mukherjee, Bharati. “The Management of Grief.” In The Middleman and Other Stories. New York: Grove Press, 1988. Pandya, Sudha. “Bharati Mukherjee’s Darkness: Exploring Hyphenated Identity.” Quill 2, no. 2 (December 1990): 68–73.

Share this:

Categories: Literature , Short Story

Tags: American Literature , Analysis of Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief , appreciation of Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief , Bharati Mukherjee , Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief , Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief criticism , Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief essays , Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief guide , Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief notes , Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief plot , Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief structure , Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief themes , critiicsm of Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief , essays of Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief , guide of Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief , Indian Writing in English , Literary Criticism , notes of Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief , plot of Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief , structure of Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief , summary of Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief , themes of Bharati Mukherjee's The Management of Grief

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment.

“The Management of Grief” by Bharati Mukherjee Essay (Review)

Short story analysis: critical review, “the management of grief”: summary, “the management of grief”: analysis conclusion, works cited.

To begin with, let us state that the story under consideration is the short story under the title “The Management of Grief” by Bharati Mukherjee. She is and outstanding American writer who was awarded a National Book Critics Circle Award in 1988 for her book “The Middleman and Other Stories.” The stories are known for their engaging plots, well-thought structures and author’s writing style. We should admit that the story under consideration is a remarkable piece of writing that deserves our attention.

It is the only story about immigrants in Canada in her collection of books. In “The Management of Grief,” Mukherjee analyzes the catastrophe that is based on the 1985 terrorist bombing of an Air India jet occupied mainly by Indian immigrants that live in Canada. “The Management of Grief” analysis essay shall define the main lesson from the story by Bharati Mukherjee.

The story uses a first-person narrative, and it makes it moving and realistic. It is a mixture of narration and dialogue. The text abounds in specific terms, naming traditional Indian clothes and dishes. This creates a realistic atmosphere and makes the understanding of the theme easier for the reader. We feel as if we were members of their community of immigrants ourselves. So, the setting is the Indian community in Toronto struck by a heavy loss.

The “The Management of Grief” theme may be observed in the title; that is why we can say that it is suggestive. “The Management of Grief” tells us there exists such grief that every person has to face sooner or later. It is the death of our near and dear people, people who represent all lovely qualities of life for us, people who are the sense of our lives.

And our task is to accept and manage this grief properly, but for the “The Management of Grief” characters, this is even more complicated because they live in a foreign country with different traditions and mentality.

The message of the story can be formulated like this: every person is free to decide how to act in his life. The most important thing is peace in our soul that will come sooner or later, even if we have experienced severe grief. We have to look for the answers in our soul, not in the traditions and customs of our country.

As we have already mentioned, the story is told in the first person. The storyteller is Shaila Bhave, a Hindu Canadian who knows that both her husband, Vikram, and her two sons were on the cursed plane. She is the narrator and the protagonist at the same time, so the action unfolds around her.

Shaila makes us feel her grief. It is natural that tears may well up in our eyes while reading. Speaking about other characters of the story, we should mention Kusum, who is opposed to Shaila. Kusum follows all Indian traditions and observes the morning procedure while Shaila chooses to struggle against oppressive traditions, and she rejects them because she is a woman of the new world . Josna Rege says that “Each of the female protagonists of Mukherjee’s … recent novels is a woman who continually “remakes herself” (Rege 399).

And Shaila is a real exception to the rule. She is a unique woman who is not like other Indian women. We would say that she is instead an American or European woman: strong, struggling, intelligent, with broad scope and rich inner world.

The first two pages give us the idea of Indian values. It becomes clear from the very outset, from the opening sentence: “A woman I don’t know is boiling tea the Indian way in my kitchen” (Selvadurai 91).

From the short story analysis, it is evident that the storyteller depicts with much detail the grief and sorrow of those who have experienced this tragedy using such word combinations as “monstrously pregnant” (Selvadurai 91) and “deadening quiet” (Selvadurai 92). The atmosphere becomes more and more tense, and we can see that among all those people who have come to help, Shaila wants to scream.

In this part of the story, where we also get acquainted with Pam, Kusum’s daughter, who stayed alive, because her younger sister had flown instead of her. Here we see misunderstanding between the mother and the daughter as Pam is a westernized teenager, and that is the reason for their detachment. She is closer to Shaila than to her mother.

In the development of action that covers the major part of the text, we can see Shaila’s meeting with a representative of the provincial government, Judith Templeton. Shaila goes to the coast of Ireland to look once again at that very place, where the crash of the Air India jet took place.

She is accompanied by Kusum and several more mourners, who grieve too much, but still, have to identify the bodies. Here the atmosphere is very tragic. The mother cannot accept the reality, and she still thinks that she did not lose her family , because the boy on the photo does not look like her son and, moreover, he is an excellent swimmer so that he can be alive. It is tough to be the witness of the tragedy of a woman who has lost her children.

Then we come to know that Shaila decided to return to India, and there she understood that she had to go back to Canada. This is the climax of the story. We see that the woman has chosen the right way, though she is still not sure and wants to ask her family for advice.

To conclude, let us say that Bharati Mukherjee’s “The Management of Grief” is a tragic and melancholic story, but after all, it creates the impression of an open door, that is the optimistic note of the story. A person who manages the grief will never be alone.

Rege, Josna. “Bharati Mukherjee (1940– ).” The Columbia Companion to the Twentieth-Century American Short Story. Ed. Blanche H. Gelfant and Lawrence Graver. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

Selvadurai, Shyam. Story-Wallah: short fiction from South Asian writers. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2005.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 28). “The Management of Grief” by Bharati Mukherjee. https://ivypanda.com/essays/analysis-of-short-story-the-management-of-grief-by-bharati-mukherjee/

"“The Management of Grief” by Bharati Mukherjee." IvyPanda , 28 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/analysis-of-short-story-the-management-of-grief-by-bharati-mukherjee/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '“The Management of Grief” by Bharati Mukherjee'. 28 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "“The Management of Grief” by Bharati Mukherjee." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/analysis-of-short-story-the-management-of-grief-by-bharati-mukherjee/.

1. IvyPanda . "“The Management of Grief” by Bharati Mukherjee." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/analysis-of-short-story-the-management-of-grief-by-bharati-mukherjee/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "“The Management of Grief” by Bharati Mukherjee." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/analysis-of-short-story-the-management-of-grief-by-bharati-mukherjee/.

- “Two Way to Belong in America” by Bharati Mukherjee

- Bharati Mukherjee’s "The Tiger’s Daughter" and "Wife" Comparison

- Bharati Mukherjee's Novels: Similarities and Differences

- Immigrant Yifeng Chang in Jen's "Typical American"

- Two Ways to Belong in America

- Globalization, Food, and Ethnic Identity in Literature

- Financial Analysis of Kroger Company

- Decision Making in Organizations

- "How to Talk to a Hunter" by Pam Houston

- The "Esperanza Rising" Novel by Pam Muñoz Ryan

- Poe's life and how it influenced his work

- Ronald Takaki: A Different Mirror

- “The Things They Carried” by Tim O’Brien

- Role of Women in Society: Charlotte P. Gilman's "The Yellow Wallpaper"

- Symbolism in "The Yellow Wallpaper" by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- Earth and Environment

- Literature and the Arts

- Philosophy and Religion

- Plants and Animals

- Science and Technology

- Social Sciences and the Law

- Sports and Everyday Life

- Additional References

- College & Higher Education Pathways

- News wires white papers and books

The Management of Grief

Bharati Mukherjee 1988

Author Biography

Plot summary, historical context, critical overview, further reading.

“The Management of Grief” is a poignant fictional account of one woman’s reaction to the 1985 bombing of Air India Flight 182. It was first published in 1988 in the collection The Middleman and Other Stories, winner of the 1988 National Book Critics Circle Award. “The Management of Grief” tells the story of Shaila Bhave, an Indian Canadian Hindu who has lost her husband and two sons in the crash. In third person narration, Shaila recounts the emotional events surrounding the event and explores their effects on herself, the Indian Canadian community, and mainstream Euro-Canadians. The clumsy intervention of a government social worker represents the missteps of the Canadian government in the general handling of the catastrophe.

Mukherjee herself had a deep personal response to the crash, having lived in Canada from 1966 to 1980 with her husband, Clark Blaise. She was enraged by the Canadian government’s interpretation of the crash as a foreign, “Indian” matter when the overwhelmingly majority of the victims were Canadian citizens. In a book-length investigation and account of the incident, The Sorrow and the Terror, co-written with Blaise, Mukherjee pieces together the bombing and events leading up to it, charging the government with ignoring clear signs of Khalistani terrorism cultivated on Canadian soil. Mukherjee argues that the government dismissed the escalating Indian Canadian factionalism (e.g. Canadian Khalistanis vs. Canadian Hindus) as a “cultural” struggle that would be best settled among the “Indians.” She blames Canada’s official policy of “multiculturalism,” which ostensibly encourages tolerance and equality but effectively fosters division and discrimination across racial boundaries.

The Sorrow and the Terror is a moving, non-fictional precursor to “The Management of Grief,” articulating the human costs of the escalations of intra-ethnic Indian conflict whose reach does not exempt the country’s North American emigrants. As Shaila laments: “We, who stayed out of politics and came half way around the world to avoid religious and political feuding, have been the first in the World to die from it.”

Bharati Mukherjee was born in Calcutta, India on July 27, 1940. Her father was a renowned chemist with connections around the globe. She and her two sisters were educated in India, England and Switzerland. At the age of three she spoke English along with her native Bengali. Mukherjee received her B.A. in English Literature from the University of Calcutta in 1959 and an M.A. in English and ancient Indian culture from the University of Baroda in 1961. She received her M.F.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Iowa in 1963 and 1969 respectively. In 1964 she married Clark Blaise, a fellow writer in the Iowa Writers Workshop. The “culture shock” of the midwest, not to mention America in general, profoundly affected Mukherjee; many of her works, like Jasmine (1989) and The Middleman and Other Stories (1988), dramatize the uniqueness of the immigrant’s struggle in the “heartland.”

Mukherjee’s academic resume is impressive: she has taught literature and writing at Marquette University, the University of Wisconsin -Madison, McGill University , Skidmore College, Mountain State College, Queens College and Columbia University . She is now Distinguished Professor at the University of California at Berkeley. She is also an award-winning writer of both fiction and non-fiction. Her first novel, The Tiger’s Daughter (1975), was a finalist for the Governor General’s Award of Canada, and The Middleman and Other Stories (1988) won the National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction that year.

Mukherjee remembers Canada bitterly as an angry, racist nation. In a 1989 interview with The Iowa Review, she remarks that in her nearly 15 years of residence there, the country never ceased making her feel like a “smelly, dark, alien other.” Mukherjee blames Canada’s policy of “multiculturalism” for engendering this atmosphere of thinly veiled racism. “The Management of Grief” speaks out against the social ills generated by this policy. In this story, the tragedy of the Air India Flight 182 brings the racial divisions of Canadian society into sharp relief. Shaila Bhave’s perspective is much like Mukherjee’s own, criticizing the government for dismissing the catastrophe as an “Indian” incident when over 90% of the passengers were Canadian citizens. The clumsy treatment of crash victims’ relatives by Judith Templeton, the government social worker, represents mainstream culture’s ignorant perception of ethnic citizens as “not quite,” second-class, Canadians.

“The Management of Grief” opens with the chaos at Shaila Bhave’s Toronto home. Her house is filled with strangers, gathered together for legal advice, company, and tea. Dr. Sharma, his wife, their children, Kusum and “a lot of women [Shaila] do[esn’t] know” are trying to make sense of the crash of Air India Flight 182, simultaneously listening to multiple radios and televisions to catch some news about the event. The Sharma boys murmur rumors that Sikh terrorists had planted a bomb. Shaila narrates the scene from a haze, speaking with detached, shell-shocked calm. The Valium she has been taking contributes to her stable appearance, but inside she feels “tensed” and “ready to scream.” Imagined cries from her husband and sons “insulate her” from the anxious activity in her house.

Shaila and Kusum, her neighbor and friend, are sitting on the stairs in Shaila’s house. Shaila reminisces about Kusum and Satish’s recent house-warming party that brought cultures and generations together in their sparkling, spacious suburban home: “even white neighbors piled their plates high with [tandoori]” and Shaila’s own Americanized sons had “broken away” from a Stanley Cup telecast to come to the party. Shaila somberly wonders “and now . . . how many of those happy faces are gone.” Implicitly Shaila feels “punished” for the good success of Indian immigrant families like hers and Kusum’s. Kusum brings her out of her reverie with the question: “Why does God give us so much if all along He intends to take it away?”

Shaila regrets her perfect obedience to upper-class, Indian female decorum. She has, for instance, never called her husband by his first name or told him that she loved him. Kusum comforts her saying: “He knew. My husband knew. They felt it. Modern young girls have to say it because what they feel is fake.” Kusum’s first daughter Pam walks into the room and orders her mother to change out of her bathrobe since reporters are expected. Pam, a manifest example of the “modern young girls” that Kusum disdains, had refused to go to India with her father and younger sister, preferring to spend that summer working at McDonald’s. Mother and daughter exchange harsh words, and Pam accuses Kusum of wishing that Pam had been on the plane, since the younger daughter was a better “Indian.” Kusum does not react verbally.

Judith Templeton, a Canadian social worker, visits Shaila, hoping Shaila can facilitate her work with the relatives of the deceased. Judith is described as young, comely and professional to a fault. She enlists Shaila to give the “right human touch” to the impersonal work of processing papers for relief funds. Judith tells Shaila that she was chosen because of her exemplary calm and describes her as a “pillar” of the devastated Indian Canadian community. Shaila explains that her seemingly cool, unaffected demeanor is hardly admired by her community, who expect their members to mourn publicly and vocally. She is puzzled herself by the “calm [that] will not go away” and considers herself a “freak.”

The story moves to Dunmanus Bay, Ireland, the site of the crash. Kusum and Shaila are wading in the warm waters and recalling the lives of their loved ones, imagining they will be found alive. Kusum has not eaten for four days and Shaila wishes she had also died here along with her husband and sons. They are joined by Dr. Ranganathan from Montreal, another who has lost his family, and he cheers them with thoughts of unknown islets within swimming distance. Dr. Ranganathan utters a central line of the story: “It’s a parent’s duty to hope.” He scatters pink rose petals on the water, explaining that his wife used to demand pink roses every Friday. He offers Shaila some roses, but Shaila has her own gifts to float— Mithun’s half finished model B-52, Vinod’s pocket calculator, and a poem for Vikram, which belatedly articulates her love for him.

Shaila is struck by the compassionate behavior of the Irish and compares them to the residents of

Toronto, unable to image Torontonians behaving this open-heartedly. Kusum has identified her husband. Looking through picture after picture, Shaila does not find a match for anyone she knows. A nun “assigned to console” Shaila reminds her that faces will have altered, bloated by the water and with facial bones broken from the impact. She is instructed to “try to adjust [her] memories.”

Shaila leaves Ireland without any bodies, but Kusum takes her husband’s coffin through customs. A customs bureaucrat detains them under suspicion of smuggling contraband in the coffin. In her first public expression of emotion, Shaila explodes and calls him a “bastard.” She contemplates the change in herself that this trauma has wrought: “Once upon a time we were well-brought-up women; we were dutiful wives who kept our heads veiled, our voices shy and sweet.”

From Ireland, many of the Indian Canadians, including Shaila, go to India to continue mourning. Shaila describes her parents as wealthy and “progressive.” They do not mind Sikh friends dropping by with condolences, though Shaila cannot help but bristle. Her grandmother, on the other hand, has been a prisoner of tradition and its gender expectations for most of her life. She was widowed at age sixteen and has since lived a life of ascetic penitence and solitude, believing herself to be a “harbinger of bad luck.” Shaila’s mother calls this kind of behavior “mindless mortification.” While other middle-aged widows and widowers are being matched with new spouses, Shaila is relieved to be left alone, even if it is because her grandmother’s history designates her as “unlucky.”

Shaila travels with her family until she is numb from the blandness of diversion. In a deserted Himalayan temple, Shaila has a vision of her husband. He tells her: “You must finish alone what we started together.” Knowing that her mother is a practical woman with “no patience with ghosts, prophetic dreams, holy men, and cults,” Shaila tells her nothing of the vision but is spurred to return to Canada.

Kusum has sold her house and moved into an ashram, or retreat, in Hardwar. Shaila considers this “running away,” but Kusum says it is “pursuing inner peace.” Shaila keeps in touch with Dr. Ranganathan, who has moved to Montreal and has not remarried. They share a melancholy bond but are comforted to have found new “relatives” in each other.

At this point, Judith has done thorough and ambitious work observing, assessing, charting and analyzing the grief of the Indian Canadians. She matter-of-factly reports to Shaila that the community is stuck somewhere between the second and third stage of mourning, “depressed acceptance,” according to the “grief management textbooks.” In reaction to Judith’s self-congratulatory chatter, Shaila can only manage the weak and ironic praise that Judith has “done impressive work.” Judith asks Shaila to accompany her on a visit to a particularly “stubborn” and “ignorant” elderly couple, recent immigrants whose sons died in the crash. Shaila is reluctant because the couple are Sikh and she is Hindu, but Judith insists that their “Indian-ness” is mutual enough.

At the apartment complex, Shaila is struck by the “Indian-ness” of the ghetto neighborhood; women wait for buses in saris as if they had never left Bombay. The elderly couple are diffident at first but open up when Shaila reveals that she has also lost her family. Shaila explains that if they sign the documents, the government will give them money, including air-fare to Ireland to identify the bodies. The husband emphasizes that “God will provide, not the government” and the wife insists that her boys will return. Judith presses Shaila to “convince” them, but Shaila merely thanks the couple for the tea. In the car Judith complains about working with the Indian immigrants, calling the next woman “a real mess.” Shaila asks to be let out of the car, leaving Judith and her sterile, textbook approach to grief management.

The story ends with Shaila living a quiet and joyless life in Toronto. She has sold her and Vikram’s large house and lives in a small apartment. Kusum has written to say that she has seen her daughter’s reincarnation in a Himalayan village; Dr. Ranganathan has moved to Texas and calls once a week. Walking home from an errand, Shaila hears “the voices of [her] family.” They say: “Your time has come, . . . Go, be brave.” Shaila drops the package she is carrying on a nearby park bench, symbolizing her venture into a new life and her break with an unproductive attachment to her husband and sons’ spirits. She comments on her imminent future: “I do not know where this voyage I have begun will end.” Nevertheless, she “drops the package” and “starts walking.”

Shaila Bhave

Shaila is the central character of “The Management of Grief.” Her third person voice narrates the story and offers poignant reflection, provocative implications and subtle irony. Her tone can be described as understated and detached, but it is by no means dispassionate. Like the appearance of calm that masks her “screaming” within, the even, often soothing tone of the narrative voice stretches thinly over Shaila’s rage and pain. She is shell-shocked by the rapid succession of devastating events.

Shaila’s husband and two sons have been the killed in the crash of Air India Flight 182. Some consider her callous and insensitive for not openly grieving, but Judith Templeton, the government social worker, hears that she is a “pillar” of the community and solicits her help. Shaila scorns Judith’s textbook methods of “managing” grief but agrees to play the cultural liaison out of politeness. Shaila wishes she could “scream, starve, walk into Lake Ontario , [or] jump from a bridge.” She considers herself a “freak,” helplessly overtaken by a “terrible calm.”

Like many others, Shaila harbors hopes that her family is still alive. She travels to Ireland to identify and possibly recover the bodies of the deceased. When called by the police to identify a body thought to be her son, Shaila insists that it is not him. She is unable to provide a positive identification of any of her family members.

From Ireland, Shaila goes to India. Her “progressive” parents encourage her to avoid falling into self-destructive depression and mourning, the “mindless mortification of her grandmother.” She is discomfited by Sikh friends who pay their condolences and admires her parents’ unprejudiced attitude, noting that in Canada the crash will likely revive Sikh-Hindu animosity. In a Himalayan temple, Shaila sees Vikram in a vision. He commands her to “finish alone what we started together.” Taking this as an injunction to resume a forward moving life, she returns to Canada. Unlike many of the others, Shaila does not remarry. She assumes that friends and relatives in India avoid matching her up because of her “unlucky” history (her grandmother’s husband died when he was nineteen). For this, Shaila is relieved.

Shaila accompanies Judith to a ghetto tenement to visit a helpless Sikh couple whose sons have died in the crash. Shaila is struck by the poverty and concentrated ethnicity of their apartment building. Just as Shaila could not bear to identify any of the bodies in Ireland, the couple refuses to sign Judith’s documents, even though they entitle them to relief funds. Despite Judith’s urgings, Shaila does not press them to sign, remembering Dr. Ranganathan’s adage: “It is a parent’s duty to hope.” They leave the apartment without signatures, and in the car Shaila can no longer tolerate Judith’s complaints about “stubborn” and “ignorant” Indian Canadians, recalcitrant textbook subjects, and asks Judith to stop so that she can get out.

Shaila has made a tolerable life for herself with the profits from the sale of her and Vikram’s house. But she is living joylessly and mechanically; she “waits,” “listens,” and “prays.” She is falling prey to the “mindless mortification” of her grandmother. The turning point is when Shaila hears the voices of her “family.” They tell her: “Your time has come . . . Go, be brave.” Shaila drops the symbolic “package” on a park bench and “starts walking” toward a life of healing and hope.

Vikram Bhave

Vikram is Shaila’s husband and is killed in the Air India crash. In a vision, he tells Shaila: “You’re beautiful” and more importantly, “What are you doing here? . . . You must finish alone what we started together.” He appears to her healthy and whole, “no seaweed wreathes in his mouth” and speaking “too fast, just as he used to when we were an envied family in our pink split level.”

Vinod and Mithun Bhave

Shaila and Vikram’s two sons, Vinod and Mithun, were also killed in the crash. Vinod was going to be fourteen in a few days. His brother, Mithun, was four years younger. The boys were going down to the Taj with their father and uncle for Vinod’s birthday party.

Elderly Couple

Because their sons have been killed in the crash, the elderly couple that Judith and Shaila visit are entitled to government relief funds, including air-fare to Ireland. They speak little English and live in a tenement building inhabited by Indians, West Indians, and a “sprinkling of Orientals.” Judith Templeton has visited them several times, imploring them to sign government documents that will entitle them to the funds. Because they are poor and unable to write a check, their utilities are being cut off one by one. Notwithstanding, they refuse to sign Judith’s papers. The husband places his faith in God, uttering: “God will provide, not [the] government.” The wife believes her sons will return to take care of them.

Kusum has lost her husband, Satish, and her unnamed second daughter in the plane crash. She had moved into the well-to-do Toronto suburb with her family, across the street from Shaila and Vikram, less than a month before the crash and hosted a welcoming party to celebrate their success. She is with Shaila in Ireland identifying bodies and hoping for life. Her husband’s body is discovered and she takes it in a coffin to India. When Kusum moves back to India to follow a life of mourning, Shaila accuses her of “running away.” Kusum responds that this is her way of finding “inner peace.” She writes Shaila at the end of the story to inform her that she has seen her husband and daughter. On one pilgrimage she spotted a young girl who looked exactly like her deceased daughter. Noticing Kusum staring at her, the young girl yelled “Ma!” and ran away. Kusum alludes to suicide in Ireland when she remarks to Shaila at Dunmanus Bay: “That water felt warm.”

Pam is Kusum’s oldest daughter and would have been on the plane had she not refused to visit India. Pam is represented as irreverent and “westernized.” She works at McDonalds, preferring “Wonderland” to Bombay, and is “always in trouble”, “dat[ing] Canadian boys and hang[ing] out in the mall, shopping for tight sweaters.” Her lifestyle and attitude strain her relationship with her traditional Indian mother, who in a moment of self-pitying despair blurts: “If I didn’t have to look after you now, I’d hang myself.” Deeply hurt by this remark (“her face goes blotchy with pain”), Pam retorts: “You think I don’t know what Mummy’s thinking? Why her? That’s what. That’s sick! Mummy wishes my little sister were alive and I were dead!” She later heads for California to do modeling work or open a “yoga-cum-aerobics studio in Hollywood” with the insurance money. She ends up in Vancouver, working at a cosmetics counter “giving makeup hints to Indian and Oriental girls.” She sends Shaila “postcards so naughty I daren’t leave them on the coffee table.”

Dr. Ranganathan

Dr. Ranganathan is a well-to-do and respected electrical engineer who has also lost his family in the crash. The reader is introduced to him when he meets Shaila and Kusum searching for hope on the southwestern coast of Ireland. He suggests to the women that survivors may have been able to swim to uncharted islets and gives Shaila hope that both her sons may have survived given that “[a] strong youth of fourteen . . . can very likely pull to safety a younger one.” He succors a sobbing Kusum and offers the story’s central phrase: “It’s a parent’s duty to hope,” continuing that “It is foolish to rule out possibilities that have not been tested. I myself have not surrendered hope.” He has taken pink roses from someone’s garden and scatters them on the water in memory of his wife. She had demanded that he bring her pink roses every Friday. He would bring them and playfully reproach: “After twenty-odd years of marriage you’re still needing proof positive of my love.”

Dr. Ranganathan accompanies Shaila to look through photographs of recovered bodies, offering her the comfort of a “scientist’s perspective.” Understanding Shaila’s psychological defenses, he looks at the pictures for her and does not force her to make positive identifications. He identifies the boys thought to be Vinod and Mithun as the Kutty brothers, bringing Shaila great relief.

Back in Canada, Dr. Ranganathan continues to be a source of comfort for Shaila. Both have not remarried and he calls Shaila twice a week from Montreal. He considers himself and Shaila as “relatives,” joined together by race, culture and now this mournful event. He takes a new job in Ottawa but cannot bear to sell his house in Montreal, choosing rather to drive 220 miles a day to work. His grief also prevents him from sleeping in the bed he shared with his wife, so he sleeps on a cot in his large, empty house. Describing his house as a “temple” and his bedroom as a “shrine,” Dr. Ranganathan, for all the comfort he offers to others, is also crippled by his pain.

At the end of the story, Dr. Ranganathan moves to Texas to start a new life, a place where “no one knows his story and he has vowed not to tell it.” He continues to call Shaila, but only once a week.

Satish is Kusum’s husband who died in the plane crash.

Shaila’s grandmother

Though only briefly mentioned, Shaila’s grandmother has an important effect on Shaila’s sense of self. She is portrayed as a traditional Brahmin woman who unquestioningly fills her role as wife and female, in other words, as a submissive and second-class citizen. Her husband, Shaila’s grandfather, died of diabetes when he was nineteen, leaving his wife a widow at age sixteen. Considering herself a “harbinger of bad luck,” she shaved her head and lived in self-imposed suffering and seclusion.

Shaila”s Mother